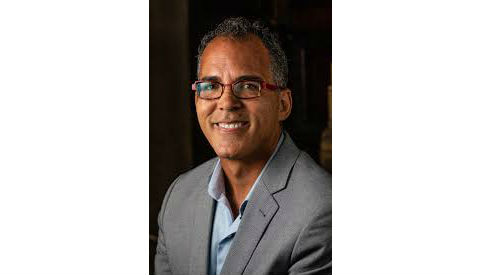

In response to the events that occured in Christchurch, New Zealand, Spiritual Life and Interfaith Coordinators hosted an event on April 4 about the term ‘Islamophobia’ and its problematic implications. The talk featured University of Washington, Tacoma Professor Turan Kayaoglu.

Kayaoglu, a Turkish-born Muslim, shared his experience coming to the United States as an international student in 1997, and how public perception of him changed after 9/11.

“I came here as a Turk; 9/11 happened and then I became a Muslim,” Kayaoglu said. “Whether I liked it or not everyone including the state I lived in … projected particular identities and attitudes, particular experiences and inclinations on me.”

Throughout his talk, Kayaoglu posed questions for those in attendance, encouraging them to engage with the term Islamophobia in order to better understand its inadequacies. Students were specifically encouraged to think about the term in two parts: “Islam” and “phobia.”

“Think about a phobia … what’s the image you have?” Kayaoglu said. “Like claustrophobia … it’s very much irrational … something we cannot control. … Should the term be muslimophobia or Islamophobia? Does the difference matter?”

A discussion followed on the distinction between religion and its practitioners. Students pointed out that unlike Muslims, Islam is an abstract idea, an easier scapegoat for hidden aggressions toward its practitioners. Many noted that “Islamophobia” detracts from the people affected by such blatant verbal attacks, revealing that such acts are based on not only religion, but race, culture and politics.

“Muslims have, in this age, basic rights, human rights. … but when we talk about Islam … we are talking about a collection of ideas, attitudes, practices, aesthetic understandings that has developed over centuries,” Kayaoglu said.

Kayaoglu mentioned other possible terms that could be used in place of Islamophobia that he felt posed important questions to ask when discussing the motivations behind such violent acts against Muslims.

“What about anti-muslimness, or anti-muslim racism?” Kayaoglu asked. “When we say racism … after all, this is Islam, we are talking about a religion. Think about two cases … a white American from Puyallup who converted to Islam yesterday versus someone who is … from Egypt whose family has belonged to the Catholic church for the last eighteen, seventeen hundred years … which one is going to get the most hatred because of Islamophobia?”

Kayaoglu stressed that the public has a preconceived notion of what a typical Muslim looks like, yet often this falls very short, unsurprisingly, from reality.

“Muslims come in all different colors, shapes and sizes,” Kayaoglu said. “Does it make any sense? The most people in the United States getting most islamophobic attacks are not even Muslim, they are Sikhs.”

The chat then moved toward understanding the reasons for such mystification and alienation of Muslims. Kayaoglu discussed the demonization of minority groups, weaving Muslims into a long thread of marginalized groups who have been historically ostracized both in the United States and globally.

“Sometimes in order to define our identity, we first create an ‘other,’ we project … negative attributes to that ‘other,’” Kayaoglu said. “The ‘us’ and ‘other’ kind of require each other. The United States … is always looking for … the ‘other,’” Kayaouglu said.

Kayaoglu discussed three historical contributors to Islamophobic sentiment as debated in academia, the first being the Crusades, which involved what Kayaoglu considers the “epistemic anxieties” caused by the Muslim Ottoman Empire competing with the Roman Catholic Empire. Next, Kayaoglu cited the European and American imperialism and racist thoery prevalent within the 19th century, and finished by addressing American stances on various issues in Middle Eastern countries such as the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Students went on to discuss military intervention and American stances on the Iranian Revolution and the Israel-Palestine conflict, as well as how the media’s persistently violent depiction and stereotyping of Islam has contributed to a contentious attitude toward Muslim and Middle Eastern-appearing people.

“At what point does it stop being about Muhammad, the Quran and Islam, and start becoming about Muslims?” Kayaoglu asked. “How can you like me by … also hating the thing that has such an important part about who I am?”

The discussion moved to freedom of speech versus freedom of religion, and the Supreme court’s support of one in favour of the other. Students specifically honed in on the violence freedom of of speech can have on minorities, especially Muslims, who already face widespread scrutiny and stereotypes from the public.

“Increasingly critical race scholars and feminist scholars are emphasizing that we cannot understand the impact of a language, whether something is protected speech or hate speech, if we are not understanding who speaks to whom and in what context,” Kayouglu said.

The discussion finished with Kayaoglu emphasizing the impact of hate speech on groups that are already marginalized, as well as how 9/11 and other sources of deeply ingrained racism have contributed to violence against Muslims.