“When we listen for resonances between these workers’ spoken theme and critical social theory about precarity,” Paul Apostolidis said, “we can recognize certain moments where such workers are speaking not only to their own experiences but also the problems that are faced by worker people at large.”

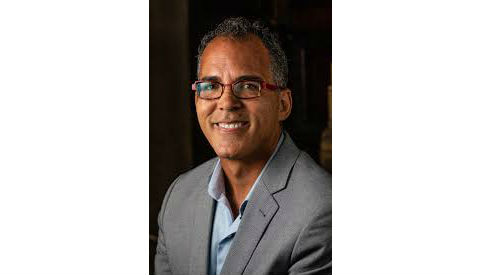

Last Friday, Professor Paul Apostolidis gave a talk on his new book, “The Fight for Time: Migrant Day Laborers and the Politics of Precarity.” Apostolidis teaches political science at Whitman College but was recently hired to teach political theory at the London School of Economics.

The talk was held in Wyatt Hall and organized by Professor Alisa Kessel from the Politics and Government Department, with support from other departments such as Hispanic Studies, Latinx Studies and Global Development Studies. The audience was mostly students from Politics and Government classes, including Professor Karl Fields’ PG 328 course, which was cancelled for students to attend the event.

“I thought it was important because we are looking at issues of development and exploitation,” Fields said. “We’ve also read stuff over the course of the semester on workism and some of the ways in which these same issues of priority are not just about peripheral versus core workers … but a condition all workers are facing.”

“The Fight for Time” centers around interviews Apostolidis conducted with approximately 80 migrant workers at two worker centers, Casa Latina in Seattle, WA and Voz: Workers Rights Education Project in Portland, OR. According to Apostolidis, worker centers are non-profit organizations that are an alternative to traditional worker unions, and typically serve low-wage workers specifically.

Day laborers, the subject of Apostilidis’ book and lecture, are contracted and paid by day. Due to the undocumented status of many such laborers, they are often exploited by employers who pay cheap wages, cheat them of their pay altogether and place them in dangerous work environments.

As Professor Kessel mentioned in her introduction, Apostolidis refers to these interviewees as “co-theorists,” a unique practice in the field of political theory.

Apostolidis’ research focuses on the idea of “precarity,” a term he coined to describe the contradictory, unstable experience of most day laborers. Within his book, he draws a connection between the instability that day laborers face and that experienced by the average American worker — albeit at varying degrees.

Apostolidis shared that much of his work is founded on the theory of “popular education” by Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire.

“Popular education centrally involves a kind of dialogue … in which all participants come to the dialogue understanding that they have important things to learn from each other, and people reject the idea of a hierarchy between those who supposedly know and those who are supposedly ignorant,” Apostolidis said.

Within such dialogues, Apostolidis explained that one can begin to find themes that unite other experiences, which then could be used in popular education; Freire called them “generative themes.”

“Part of the aim for my project was actually to produce information like this about themes that Voz and Casa Latina could use in popular education programs with day laborers,” Apostolidis said. “But at the same time one major goal of popular education is to bring together people from different social backgrounds who are confronted in common with overarching forms of domination.”

From his interviews, Apostolidis found three common generative themes that constituted precarity: Desperate Responsibility, Fighting for the Job and Facing Risks On All Sides/Keeping Eyes Wide Open, which all contribute to the paradoxical and unstable experience of the day laborer. The majority of Apostolidis’ talk was dedicated to explaining each theme, including how they came directly from workers’ narratives.

Apostolidis began with his first theme, claiming that day laborers often are not able to find jobs, which perpetuates a sense of desperation and personal responsibility for their failure to find one.

“Despite the fact that they are constantly on the hunt for jobs, they are usually able to find work only two days a week,” Apostolidis said. “They earn very little wages … and they are all really really poor.”

Furthermore, due to day laborers’ unstable unemployment situation, most experience a sense of constant anxiety. This led to Apostolidis’ second theme of Fighting for the Job.

Apostolidis explained that day laborers, though in active search for jobs, often are stuck waiting most of the time for an employer to pass by, which exacerbates feelings of anxiety. This also contributes to stigmatized images of day laborers that contradicts each other.

“If day laborers are just standing around in the corner then people assume that they are loitering, or maybe involved in some kind of criminal activity like selling drugs. But also someone who witnesses from afar workers rush up to the car and try to jump up into the backseat think they are violent threats to the social order,” Apostolidis said. “Either way it’s the worker only bodily action. Ironically … it attracts vengeance by authority to discipline.”

According to Apostolidis’ co-theorists, “bad workers” try to extend their working hours by doing the job at a slower rate, whereas “good workers” go as quickly and efficiently as possible to please the employer. Apostolidis pointed out that most American workers are in a similar constant competition for jobs, which leads to the same desperate decision-making that day laborers are prone to.

“Increasingly we all have to fight to take what we can get, rather than making rational choices in a dispassionate way between competing alternatives,” Apostolidis said.

This sort of competition leads many day laborers to take any kind of job they can; therefore, they are constantly being placed into risky working conditions, which also heightens their sense of personal responsibility for their own well-being. This involves Apostolidis’ third theme: Facing Risks On All Sides/Keeping Eyes Wide Open.

“With any given year, a day laborer has a 20 to 30 percent chance of sustaining a serious job-related injury or health problem,” Apostolidis said.

According to his interviews, Apostolidis explained that those who brought their own protective equipment were thought to be the better workers, even though many times, due to the constant change of work places, the protective equipment was not appropriate for the job.

Apostolidis also discussed that the average American worker experiences risks at their jobs as well, though at a far lower level than the day laborer. A few of his examples were environmental pollution and musculoskeletal problems, as well as the risk of heart disease caused by the anxiety over losing one’s job, or not being able to find permanent employment. Meanwhile, many workers also assume personal responsibility to minimize their precarious situation.

“How many of us find ourselves getting pulled into the game of trying to show personal responsibility by purchasing health commodities, like fitbits or gym memberships?” Apostolidis asked the audience. “How many of us get drawn into the habit of quasi-voluntarily … prolonging our own working days, working out for the sake of working more efficiently and for making the boss see how dedicated we are?”

“I think this talk has really interesting implications,” junior Amy Colliver said. “Especially right now in this very neoliberal world, where we are expected to have this entrepreneurship of the self … but how this manifests into this implication that you have to be working yourself to the bone in order to be successful.”

Apostolidis concluded his talk with a Q&A in which he spoke with audience members on the preliminary recommendations he left readers with in his book on how to fight precarity, such as the importance of solidarity between the average worker and day laborer. He stressed the need for a more general push from the public, such as from activist groups, and gave the example of the #Not1More movement.

Apostolidis stressed that activists should call attention to the precarious effects that detention centers and deportation have on day laborers, in addition to the equally serious issues usually cited for their abolition. In addition, he promoted more popular education programs like those in Casa Latina and Voz, and suggested that worker centers exist for all workers, not just day laborers. In fact, Apostolidis wondered during the Q&A if this should be the topic of his next book.

Apostolidis’ other works include “Breaks in the Chain: What Immigrant Workers Can Teach America about Democracy” and “Stations of the Cross: Adorno and Christian Right Radio.”