Keynote speaker James Forman Jr. had just finished discussing a recent protest in neighboring Kitsap County, which was part of an event promoted by Tarra Simmons and her criminal justice reform organization Civil Survival. Civil Survival, alongside some hundreds of protestors, had used the familiar civil rights tactic of ‘court-packing’ to bring attention to the cruel and inhumane conundrum of legals fines, fees and debts, which systematically ensnare the county’s most disadvantaged citizens.

“So, Pierce County,” Forman Jr. said, “how’s tomorrow?”

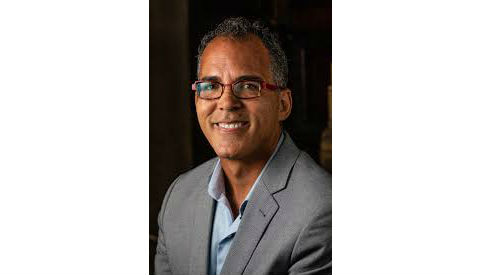

Forman Jr. was lecturing as part of Philanthropy Northwest’s Racial Equity Speaker Series, hosted last Thursday at 6 p.m. at the packed Rialto Theatre in downtown Tacoma. His talk was titled “Crime and Punishment in Black America.”

Forman Jr.’s speech ranged from biographical anecdotes about growing up as the child of an interracial couple deeply involved in the civil rights movement, to a discussion of his acclaimed 2017 nonfiction book “Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America,” to advice on strategically combatting the mass incarceration epidemic in the United States.

Philanthropy Northwest, which hosted the event, is a large network for philanthropists committed to collaborative action and equitable community-building in the states of Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming.

The first to take the stage on Thursday was current Tacoma Mayor Victoria Woodards, who acknowledged the work of Pierce County Judge Frank Cuthbertson in reducing the amount of young people in Tacoma moving through Remann Hall Juvenile Court, and recognized the partnerships between Tacoma Arts Live and local cultural organizations, as well as local institutions of higher education.

Woodards was followed by Philanthropy Northwest Program Manager Mares Asfaha, after whom came Philanthropy CEO Kiran Ahuja to introduce the main event.

In outlining Forman Jr.’s “extremely stellar” biography, Ahuja described Forman as a Pulitzer Prize Winner, Yale Law School graduate, former law clerk for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, founder of the Maya Angelou Public Charter School, and a Yale Law professor since 2011. Aside from his credentials, Ahuja emphasized the “passion and connection” Forman Jr. brings to activist work, such as teaching a class at a correctional facility and supporting young people caught in the system.

Forman Jr. then took the stage, opening his speech by recognizing that, in the context of the release of the redacted Mueller Report that morning, it was a “difficult day to talk about law in this country.” He criticized Attorney General Barr — who was tasked with providing a brief characterization of the report before its full release — as the president’s “partisan puppet,” and argued that “despair is never an option for black people in this country,” despite the futility and despair of the contemporary political atmosphere.

Forman Jr. proceeded to discuss his 2018 Pulitzer-Prize-winning book, describing it as “fundamentally a book about stories,” drawn from his experience as a public defender, a job he once saw as the civil rights work of his generation. According to Forman Jr.’s website, “Locking Up Our Own” “seeks to understand that war on crime that began in the 1970’s and why it was supported by many African American leaders in the nation’s urban centers.”

Labeling mass incarceration as a “human rights crisis,” Forman Jr. challenged audience members by asking, “What are you gonna do?”

His question pointed to the subverted reality that people, especially those involved in the criminal justice system, tend to deflect problems and deny personal responsibility at all costs.

Forman Jr. characterized the problems of the previous generation of civil rights activists, who were constrained imaginatively and thus could only conceive of calling the police as a response to drug-related incidences, whereas rehabilitation services would have been insurmountably more beneficial. Now, programs like the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program in Seattle, which “allows law enforcement officers to redirect low-level offenders … to community-based services instead of jail and prosecution,” police officers are given a different set of options and a model of collaboration that provides a stark alternative to incarceration.

Forman Jr. finished by discussing how activism can change narratives. He recalled how he found his calling as an educator, and how he has most fully expressed this through his involvement in The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, founded by Temple University professor Lori Pompa.

According to the program’s website, it aims to “facilitate dialogue and education across profound social differences,” as traditional college students and incarcerated students come together in semester-long learning.”

Forman Jr. also expressed his belief that people’s roles in social movements can be tailored to what they love or their individual skill set and emphasized the imaginative potential of taking social action. He advocated against viewing historical social movements as unified and inevitable, arguing that “not everybody was in the [civil rights] movement,” and that colleges and universities that now take pride in campus activism disowned it and distanced themselves from it at the time.

A discussion panel followed the talk, led by Aiko Bethea, Head of Diversity and Inclusion at Fred Hutchinson, a cancer research institute headquartered in Seattle. The panel featured Judge Cuthbertson and Sean Goode, the executive director of the Choose 180 Youth program, alongside Forman Jr.

The conversation ranged from vivid visual representations of the nexus between slavery and our present reality of mass incarceration experienced by Judge Cuthbertson in his daily work life, to the criminalization of public health and behavioral issues such as mental health and addiction.

The panel also pointed to innovative solutions and major policy changes to address mass incarceration, including pre-trial services, challenging unjust and damaging laws, implementing restorative justice practices, and the intentional, collective and united destruction of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Forman Jr.’s lecture imparted not only an important message about the immediacy and severity of the problems associated with mass incarceration but also challenged audience members to make themselves a more significant part of the resistance. By bringing vital and effective programs like LEAD and Choose 180 to the city of Tacoma and its many college campuses, a creative and continuously re-imagined response to mass incarceration can begin to do the difficult work of combatting the cruelty and unethical practices of the United States criminal justice system.