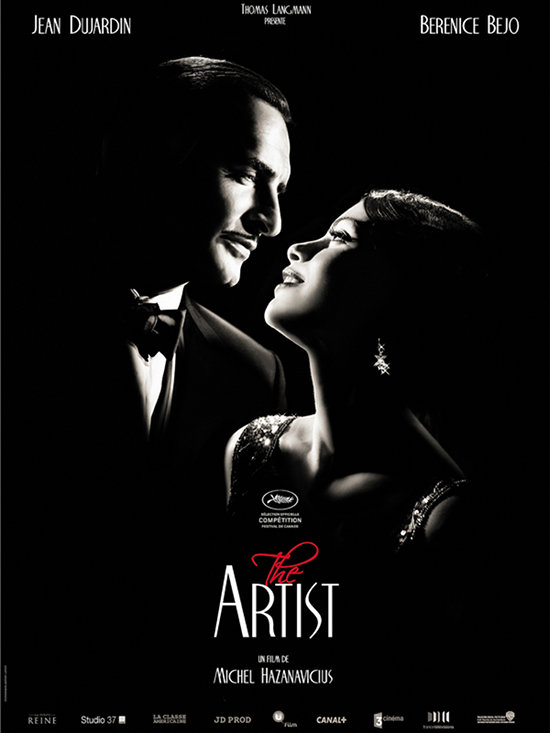

The Artist has been making itself loudly known to the world of film since its Belgian release in October 2011 and its subsequent January 2012 American release.

Directed by Michel Hazanavicius, starring Jean Dujardin and Berenice Bejo, this film has already won the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture—Comedy or Musical; Best Original Score; and Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture—Comedy or Musical, has won Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Palme d’Or. With the Academy Awards fast approaching, The Artist is in the running for 10 Oscars, from Best Cinematography to Best Motion Picture.

As if these prestigious awards weren’t enough, the film has been nominated for various awards, some of which it has already won, at more than 30 international film festivals.

Knowing it had such a vast list of honors in its back pocket, I went into the film with mild expectations: I knew it would be impressive but I was unsure whether it would hold my attention since its outstanding quality is, in fact, its silence.

The story takes place in Hollywood in 1927, in the era just before talkies became a reality. George Valentin (Dujardin) is a Don Lockwood replica, replete with all the same angst of a silent film legend facing the abrupt transition into talkies. However, The Artist departs from Singin’ in the Rain, its inevitable comparison, in its embodiment of the silent film itself and its black-and-white cinematography.

Undoubtedly one of the highlights of the film as a whole is its ability to accurately capture the somewhat fuzzy, ethereal cinematography of films from the 20s onward, a quality that seems to be missing from other modern attempts at black-and-white.

But Valentin, although he looks and tap dances like Gene Kelly, is not surrounded by a crowd of adoring friends, and he must grapple with the loss of his career with only the sporadic but sympathetic support of rising star Peppy Miller (Bejo), who got her start in movies thanks to George.

Save for two exceptional scenes that stand out all the more for being so rare, the only sounds in the hour and a half movie are soaring musical scores that do a surprisingly effective job of telling the characters’ emotions or thoughts when the spoken word cannot.

This is a film in which the symbolism is neither too overt nor too subtle, the acting is both exaggerated (as, to some extent, it must be in a silent film) and understated, and the music is by turns playful and despairing, all of which combines to create a more realistic and relatable work than would be expected from a silent, black and white movie of the 21st century.

As I left the theater, I felt struck by how effortless the film was overall. Many films that have such a distinct format are obvious in their attempts to critique a social ill or present a modern problem, but instead The Artist gently pushes one towards reflection. That reflection could lead a viewer to perceive a message about the cyclical destruction of the modern media or to a simple story of loyalty and aging and fame.

Either way, The Artist is one of the best films I’ve seen in a long time, the kind that is not afraid to look back to the days when this art form relied on nothing more than the actors, the cinematography and the music to tell a true and beautiful story.