The United States has 2.3 million people behind bars at any moment. The staggering numbers become even more surprising when broken down by racial identity: 60 percent of persons incarcerated are of color although the U.S. population is only 24 perfect non-white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The incarceration of our population becomes even more sensitive when one recognizes that black males have an imprisonment rate six times higher than white males. Black males make up 35.4 percent of the jail and prison population — even though they make up less than 10 percent of the overall U.S population.

There is a distinguished effect of black males winding up behind bars systematically when black males born in 1991 have a 29 percent chance of spending time in prison at some point in their life, whereas white males are at 4 percent. This chain of events is commonly known as the cradle to prison pipeline.

The Race and Pedagogy Initiative, located in Howarth 209C, is a collaboration of the University of Puget Sound and the South Sound community geared toward educating students and teachers to think critically about race. On October 6th, the much awaited Race, Education, and Criminal Justice Conference was held here on Puget Sound campus. The conference brought a wide range of participants together to examine and discuss the structural dynamics surrounding how a child goes from being a member of the educational system to that of the criminal system.

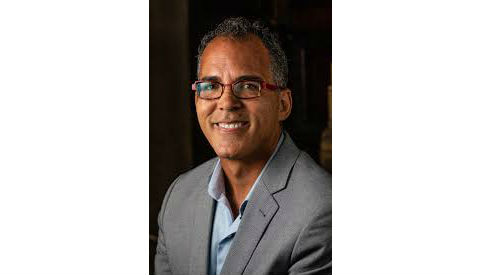

It all began with an opening from Professor Dexter Gordon, director of African American Studies and chair of the Race and Pedagogy Initiative, as he welcomed the attendants to the day’s engagements. What proceeded was an earnest telling of stories and performances as artist Paul Rucker and keynote speaker Ericka Huggins lifted the audience into an enlightened viewing with their voices and accompanied music of how widespread the prison-industrial complex has become.

The conference then broke off into separated concurrent talk sessions as participants were able to choose what they would like to discuss more in-depth.

During the session on School Discipline, Policies, and Practices, speakers Thelma Jackson, Bonnie Glenn, Greg Williamson, and Brad Brown shared with the audience how they are taking strides to keeping youth out of the prison pipeline.

Jackson spoke about how the system follows three tracks: how black males get incarcerated, what the education is like inside, and what happens after release. She stated, “Who’s not achieving in our schools has a direct correlation to who is in our prisons. The impact on our community, families, and children is beginning to take note.”

Brown, Principal of First Creek Middle School, strongly suggested restorative justice to be used in place of school disciplines like suspensions and expulsions. Instead of sending problematic children away from the safety of a school setting into the harsh reality of the streets, there could be a system in place in schools that taught kids how to respond to outside influences and not cause harm in return.

“Our youth are our present and our future, we need to help now more than ever,” added Glenn from the Juvenile Rehabilitation Admission.

One in nine black children have an incarcerated parent. Adding this to the equation gives struggling youth more barriers to overcome as they try to stray away from the path already laid out for them. Glenn asked the audience, “Do you want to know where all the 18-30 year old young black men are? They are incarcerated.”

These extra setbacks create continuous collateral consequences, which a second break out session was directed toward. Director of Equity and Achievement in Federal Way School District Erin Jones, Executive Direct of Good Shepherd Youth Outreach Louis Guiden, and Department of Corrections Professional Warren Gohl led the discussion about the difficulty in tending to the issues of re-entry and recidivation of former inmates.

Jones mentioned that prisoners need to retrain their minds, otherwise the habits they picked up will continue to be carried out in society. She focused on how everyone wants to do three B’s: belong [somewhere], believe [in something], and become [somebody].

“There’s so much work to be done. It is really tough work, but if each of us do something each day, it adds up” she said.

Guiden emphasized the economic impact that incarcerating such a high percent of individuals has on society. He said the post-released youth need an opportunity to be empowered and make a change, but they cannot do that when they can’t get a job. The constant lack of achievement adds to their tension and anger and adds to their potential to offend again.

So what can the public do to help disrupt the cradle to prison pipeline? Simply be the best person you can be to the world, encourage the children around you, and work together with community efforts to bring resources and safe environments to the at-risk youth of our nation.

PHOTO COURTESY/DYLAN WITWICKI