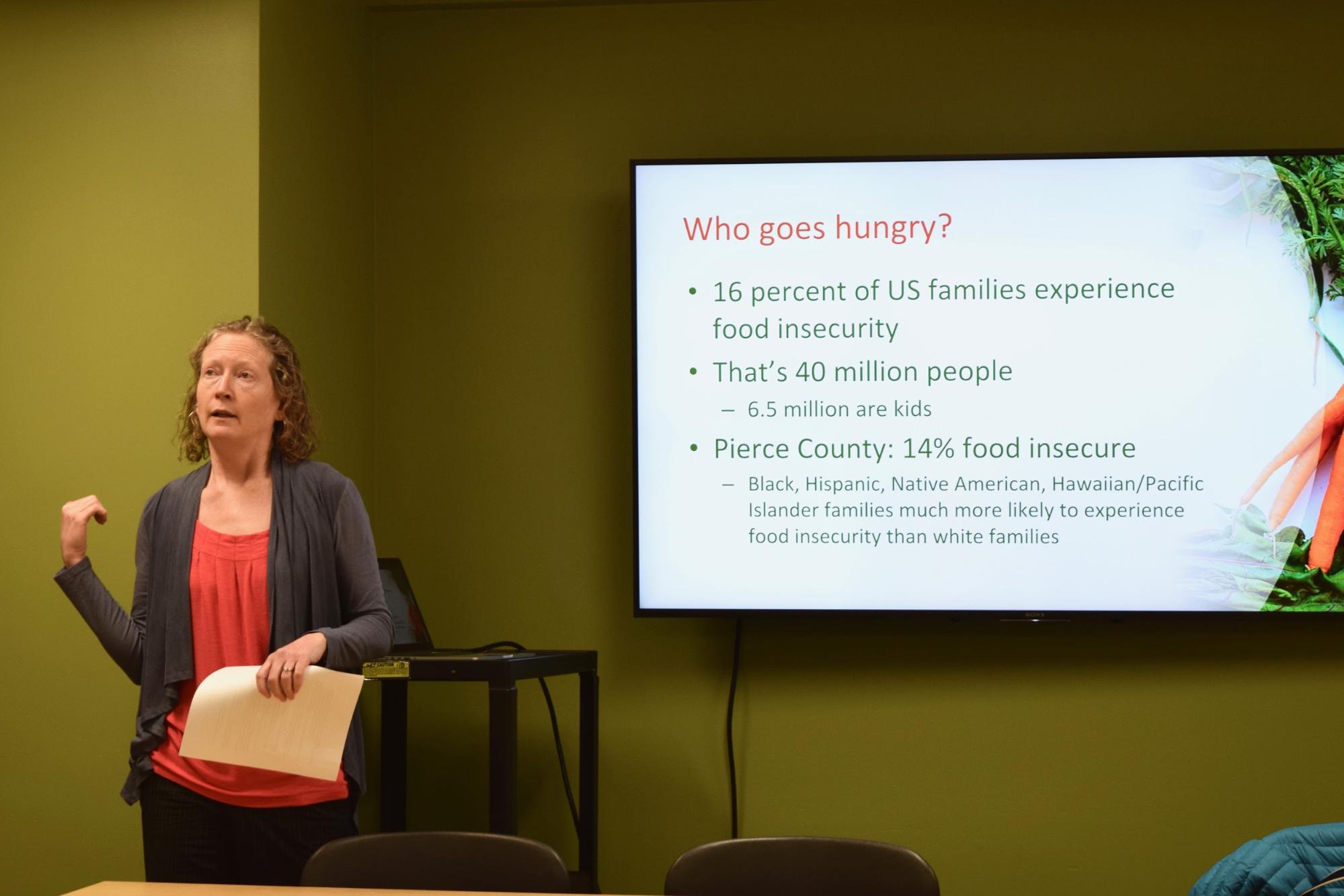

When talking about science, most students do not really think about the ethics behind it; the Bioethics Club helps students connect what they learn in the classroom with moral principles. On March 6, the Bioethics Club held a talk about food justice given by Emelie Peine, an international political economy professor.

“Bioethics is the study of the ethical implications of the scientific community’s actions, so it looks at new discoveries and how they might be ethically controversial, what parties they might discriminate against, and how they might affect the well being of different groups of people,” sophomore Annelise Phelps, the treasurer of the Bioethics Club, said.

The Bioethics Club “is mostly functioned in sort of a lecture series and we have different professors or students or community members speak [about] some topic related to bioethics that they are excited about,” Bioethics Club president Kate Gladhart-Hayes said.

“It is also a place where both people with a bioethics emphasis as well as other science majors can kind of explore the ethical side to science because I think that a lot of times that area gets neglected in traditional science classes,” Phelps said. The club does encourage students from all majors and interests to attend the talks they host one to two times per month.

Peine defined food justice as “Human rights, fair treatment and equal opportunity in the food system,” during her talk. Her talk was centered around facts such as: most of a farmer’s income comes from off-farm jobs and that 16 percent of families in the U.S. do not have access to nutritious foods.

“When I think about the food system, I really think of it even including the sort of the production, processing, sale, but also the consumption side. So we are all part of the food system even if we aren’t directly involved in any sort of agricultural activity. We are all part of it because we all eat food, so we all have a connection with the people that grow it even if we don’t think about that connection or are really aware of it,” Peine said.

She covered a wide variety of topics concerning the food system. She mentioned that most farm workers do not have proper working conditions and can’t speak up because of their immigration status or race. Peine also said that farmers are not actually employed by the farm they work for, which makes it hard on them to file a claim.

In addition, she talked about how most meat in the U.S. comes from Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), and how “everything has a dark side, including eating tofu,” Peine said.

During her presentation, Peine explained how CAFO facilities use fertilizers made of fossil fuels to grow food for the animals they keep in cages until they are turned into meat. These type of fertilizers are bad for the environment not only because they are made from fossil fuels, but also because it causes the fertilizer that the animals create to go unused, which creates pollution.

“Consumer choices are important but not enough. I think that was a really big takeaway from it because people get very hung up on that. They are like ‘Is it worth it? Is it not worth it?’” Gladhart-Hayes said. Even organic food is fertilized with the waste of animals at CAFOs, thus making it hard to break out of the cycle of mistreatment of animals and pollution.

“The choices that we make really do matter but I think that it is very easy for us to consume our way out of this problem,” Peine said. There are more actions that can be taken, such as calling representatives to ask for better conditions for farm workers, and to turn the 30 percent of our food that is produced and goes to waste into fertilizer.

People can call their representatives to ensure “the ability of small and medium size farmers to make a living farming and the ability for them to hold on to their businesses and make a living, and that is more of social and political problem than it is an economic problem. I think we often think of it as an economic problem and we have economic solutions rather than having political solutions,” Peine said.

In our community, the S.U.B. already helps reduce the ecological impact by sending the food waste to an organization called Tagro. This organization turns waste into compost and gives it to farmers for free. This compost is also used to fertilize the trees around campus and vegetables in the campus garden, which people can harvest and then eat. Students can visit the campus garden and grow some of their food.

“For me, growing a little bit of your own food is not necessarily an issue of sustainability as it is just sort of fostering that connection to where that food comes from and what it actually takes to get food onto our plates,” Peine said.

This would help people understand the struggles and hard work that farmers put into feeding others and close the gap between consumer and producer. “I feel that everyone can have a pot with a basil plant on their window,” Peine said.