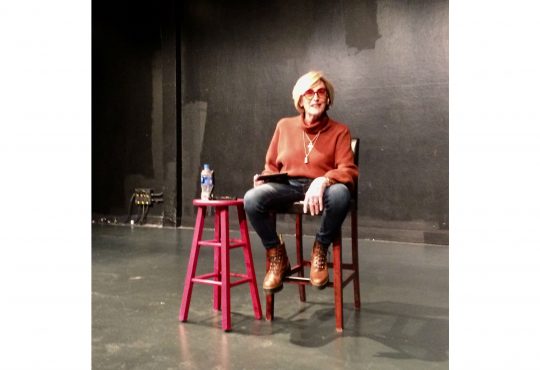

In a refreshingly honest and hard-hitting talk, politics and government Professor Alisa Kessel presented “The Classic American Rape Story” to the Puget Sound students and community on Wednesday, Nov. 7. Sponsored by the Honors Program, this event acted as both a presentation and open conversation discussing rape culture in America and its consistent narrative throughout time.

Professor Kessel began her presentation by defining three key terms in her own words. She proposed a broad overarching concept of sexual violence, followed by a more narrowed idea of hands-on sexual assault and the most specific action of rape. She made a point of differentiating these three definitions to clarify her own discussion of this topic as well as to emphasize that her discussion of rape culture more generally referred to sexual violence.

She then delved into the 2,500-year-old myth of Lucretia, a chaste woman who was raped at knifepoint and later committed suicide.

“She knew she wasn’t responsible. Everyone told her she wasn’t, but lest her example be used as an example to justify unchaste femininity, she killed herself anyway,” Kessel said. “So the paradigmatic rape story, the American version, is really the same story that’s been told in the Western tradition for centuries.”

Kessel displayed numerous examples of both Lucretia’s rape and suicide depicted by artists generations apart, noting how her story is one still recited today, 2,500 years later.

“What is it that allows this idea, this concept, this story, to endure as the story that helps us understand what counts as rape and what doesn’t count as rape?” she asked.

Naming this question as her driving force, Kessel not only explored this thinking throughout her talk, but throughout her additional work surrounding this topic as well.

“I have been studying different aspects of sexual violence for a few years and have been thinking about consent and rape culture from an intersectional perspective,” she said in an interview.

“Wednesday’s presentation was a portion of a talk I gave last summer in Passau, Germany as part of our faculty exchange with the University of Passau. I’ve also talked about rape culture at a few campus events in support of the It’s On Us work that has been happening here, and I occasionally publish opinion pieces in Crosscut, a Seattle online publication, about issues related to sexual violence.”

Following Lucretia’s story, Kessel then proposed other definitions of rape and rape culture from various sources, pondering the light in which rape culture is considered and the depth in which it is regarded. She followed up by presenting some central claims that she has made in her work on this project.

“Rape and rape culture are mutually sustaining,” she said. “The second thing I want to say is that … rape culture isn’t just about violence against women or the location of women. It’s actually about the violence against certain women and not others. … The work that rape culture does to separate victims from perpetrators and those separations are very much raced, classed, rooted in sexuality, rooted in ableist norms.”

Expanding on these claims, Kessel went into detail about how rape is often perceived as being justifiable for some victims but not for others. She noted the cause of this difference in beliefs as depending on both who the victim is and who the perpetrator is, in regards of race and class. To support this statement, she noted famous cases such as the Brett Kavanaugh case, the Brock Turner case, the Bill Cosby case and the Harvey Weinstein case.

Kessel also presented numerous advertisement images and pop culture examples in which rape culture is present. These images depicted rape in a normalized or even sexualized way, and her primary pop culture example of “Game of Thrones” further exemplified the cultural distinction between excusable and inexcusable rape.

“I undertake this research because I think it is essential political work for victims of sexual violence,” she said. “I am not doing this because it is interesting. I’m doing it because sexual violence is a pernicious problem that requires conscious and clear-minded work to eradicate. I’m trying, through my research and through educational presentations like the one on Wednesday night, to contribute to that work.”

To conclude her presentation, Kessel displayed startling statistics as to how many people have actually reported an experience of sexual violence, and voiced her hope that claiming rape culture in an intersectional way can help in ending sexual violence.