Climate change has the potential to be very detrimental to all people’s health; however, people of color are suffering most from public health issues and climate change. Historically oppressed groups, like people of color, are at a much higher risk of disease and premature death due to public health and climate-related issues.

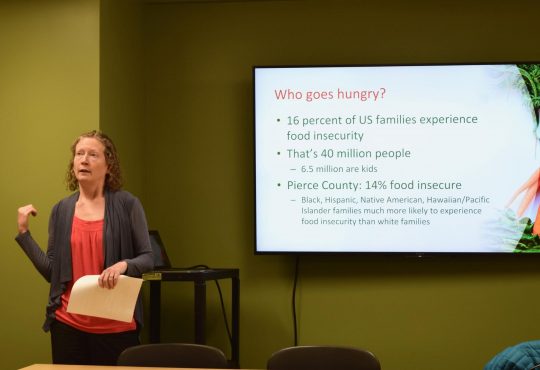

On Tuesday, March 26, a panel of speakers presented on the intersection of public health, climate change and social justice as part of the Spring 2019 Climate Justice Speakers Series at the University of Puget Sound. The speakers were Marnie Boardman, the Climate and Health Coordinator for Washington State Department of Health; Luke Sturgeon, the Health and All Policies Coordinator at Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department; and T’wina Franklin Nobles, the President and CEO of The Tacoma Urban League, an organization that works to empower local African Americans and disenfranchised groups.

The panelists explained that public health impacts due to climate change can include worsening allergies, asthma, pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, malnutrition, physical injuries and even mental health problems.

“Every person is vulnerable; no one gets out of this without having some kind of impact. But most importantly and most emphatically, some are disproportionately vulnerable,” Boardman said.

The most vulnerable tend to be people of color and they also tend to live in the most poverty-stricken neighborhoods. These neighborhoods experience a lack of resources like medical care that is desperately needed with rising environmental health detriments from climate change. Much of this is due to deep-seated institutional racism.

When analyzing life expectancy in Tacoma, Sturgeon and the Tacoma/Pierce County Department of Health found as much as a 15-year difference in the age of death between groups of predominantly white areas versus areas with mostly people of color.

“That’s a huge disparity! We have a saying in public health that your zip code, not your genetic code, determines how healthy you’ll be. Where you live in the county could mean as much as a 15-year difference in life expectancy,” Sturgeon said.

Until the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, people of color were systematically and intentionally excluded from “white” neighborhoods. The federal government took part in something called redlining, which was a systematic exclusion of services such as insurance, loans and health care to residents of certain neighborhoods. More often than not, this exclusion was racially motivated.

As part of redlining, neighborhoods were assigned grades ranking from A, meaning the safest investment for infrastructure and development, to D, meaning a very unsafe and a virtually impossible investment. Many of the D-graded neighborhoods were assigned their grade on race alone.

As an example, Sturgeon displayed a city map of Tacoma from the 1930s. It showed an area of A-graded sites surrounded by a very small D-graded site.

In explanation, the city wrote: “Three highly respected Negro families owned homes and lived in the middle block of this area facing Verde Street. While very much above the average for their race, it is quite generally recognized among realtors that their presence seriously detracts from the desirability of their neighborhood.”

This deeply upsetting message is from over 80 years ago; however, policies like these still greatly impact people of color today. Because of a historical lack of investment and infrastructure in these neighborhoods, residents have less access to job opportunities, transit, healthy food and medical care.

“There’s a long history in public health and academia of looking at data like we looked at and saying, ‘We know what’s best for the people who live in these areas.’ … It’s so much better to instead ask those people what they need … and allow them to advocate for their own health,” Sturgeon said.

This is why Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department provides funds to organizations like the Tacoma Urban League and allows them the freedom to put the money where the community needs it most.

“We’re focusing on homeowners and stable housing, affordable housing, good policy that would help us think about the communities that are impacted most by pollution and other disparities,” Nobles said of the funds provided by Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department.

The partnership of Tacoma Urban League and the Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department not only helps fund necessary community functions, but it also helps with communication. Often communities that are historically oppressed do not trust historically corrupt government organizations like Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department but do trust organizations like Tacoma Urban League.

“When T’wina mentioned the work that Tacoma/Pierce does with Tacoma Urban League, you know, the State Department of Health or local health department are not always going to be the trusted messenger for getting an exchange in health information. It is so vital to have community organizations that help to get information,“ Boardman said.

Clearly, the oppressive systems that were set up long ago still persist today and greatly impact people right here in Tacoma. The partnering of larger groups like Tacoma/Pierce County Health Department and smaller community groups like the Tacoma Urban League can begin to change Tacoma for the better by providing necessary funds, communication and support.