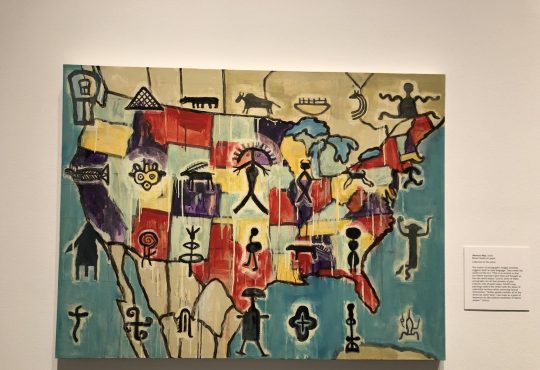

In the west wing of the Collins Memorial Library reading room, there is a painting of three young black children. The piece, entitled worlds un(sung), heads un(hung), was given the 2010 Collins Library Art Award because it promotes “ideas about diversity.”

I believe that it was a mistake in judgement to select and display the painting because it poorly represents of one of the core values that the University most earnestly promotes.

I find the placement of worlds befuddling. Because this is a work of visual art, consider the composition. The piece is a large benderboard of laminated poplar which rests on the floor. It shows three children, the full head of a smiling boy to the left, the upper body and head of a scowling boy in the middle and the head of a pensive third slightly off-frame to the right. The background is a constellation of yellow splotches and charcoal streaks.

Upon spotting the painting, one might wonder, especially if one spends a lot of time facing west in the reading room, ‘What is the purpose of this attention-grabbing piece?’ That is not evident from the painting itself, for it lacks compositional integrity. There is no gradation in the depth of field, no harmony or dissonance between the figures’ positions, no eye-catching mixtures of hue and tone. In fact, there appears to be no unifying visual element whatsoever.

Well, that last criticism is not entirely valid. The skin color of the three kids shown is the same. In the statement posted next to his work, the artist explains that our society is awash with media, including images of “the suffering of many peoples.” We often intellectualize such cultural artifacts, he explains, but in so doing, “we discard the articles and images of the less fortunate.”

The artist’s sentiment is both respectable and timely, but for all that rhetoric, the painting itself does not engage in a forward-thinking debate.

There is nothing overtly racial about the piece, besides the fact of the boys’ skin color. The artist writes, “I paint as a way of honoring those who have had to bear the externalities and collateral damage of the human race.”

By extrapolation, I assume that he means that these three black children embody the victims of systemic racism. Yet, as I stand mystified in front of the panels, I do not see any semblance of a story that might frame the figures within this context of racial victimhood. The figures are isolated from each other and their emotions, however well conveyed, correspond to no evident stimulus.

Because of these absences, the artist’s justification fills me with questions about the dubious value of his painting: ‘What does the viewer learn from seeing it?’ ‘Are these kids the victims of our collective erasure of media that testify to the suffering of people marginalized because of their ethnicity?’

Finally, I ask myself, ‘Does an ill-conceived painting of black children qualify as a legitimate participant in the hopeful racial dialogue pioneered at this very school, soon to be held at the National Race and Pedagogy Conference on Oct. 28-30? If you think of it, the one-dimensionality of such a public example of university creed adds no perspective to that dialogue.

Sadly, the painting and its rhetoric champion the kind of reductive understanding of race that a critical debate tries to avoid. It offers a naïve, guilt-based sympathy which equates flat portrayals of non-white people with an enlightened understanding of the complex sociohistoric power dynamics between ethnic groups in the United States.

For discussions of race, Puget Sound offers some sophisticated venues. In the Socratic and community-oriented style, there is the aforementioned conference. In the educational, there are the African-American, Latin-American and Asian Studies programs. In the artistic, visits like that of the acclaimed playwright Suzan-Lori Parks provide insight into explorations of racial identity.

I recommend that the library re-assess its selection criteria for public artwork, especially the examples that go beyond cultural enrichment and correspond to the core values that Puget Sound fervently espouses. Perhaps a sequence of poignant photographic portraits would do, or a mixed-media piece with symbolism that could interest a campus audience unfamiliar with the finer points of art critique.

However one chooses to define it, diversity is important, but so is the aesthetic by which one represents it. Art — if displayed for the purpose of piquing concern about a sensitive sociopolitical issue — can undermine that purpose when practical questions of tact, appeal and word-to-image correlation are not asked. Otherwise, the artwork stands 12-15 feet long and literal, a bold eyesore that raises more brows than awareness.