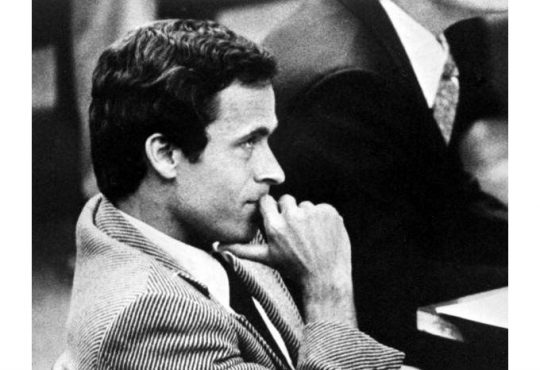

Scrolling through the annals of Logger history, it is easy to spot some famous alumni. From Rachel Martin of National Public Radio to Adam West of “Batman,” there is an abundance of well known Puget Sound alumni who have contributed immensely to popular culture, politics and society. If one former student takes the cake for most famous (or infamous), however, that honor would go to Tacoma’s very own Ted Bundy.

Yes, that’s right. One of the country’s most notorious killers walked through the same McIntyre hallways that you likely do yourself. Bundy, who took the lives of over 30 individuals in some of the nation’s most gruesome murders, is a peculiar and overlooked figure in the history of Pierce County.

Though Bundy’s story is a different era of Tacoma history, many of the relics of his past can still be found in the North End today.

Originally born in Vermont as Theodore Robert Cowell, Ted’s father left his mother soon after she became pregnant. His mother’s religious family saw this out-of-wedlock pregnancy as shameful, leading his grandparents to adopt Ted.

According to Bundy expert Kevin M. Sullivan, Bundy’s mother, Louise Cowell, was still intimately connected to him in these early years, playing a sister-like role. By the time he was 3 years old, Bundy’s mother was looking to start life anew. She moved herself and Ted to the North End of Tacoma, only a few blocks from the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

The young family quickly fell in place in the new city. According to her obituary in USA Today and The Morning News, Louise got a job as a secretary in both the Communications and Theatre departments at Puget Sound, which she held until long after Bundy’s death. Within her first few months in Tacoma, Louise met Johnnie Bundy at a singles function at First Tacoma Methodist Church.

Not long after they met, Louise and Ted moved in with Johnnie and his four children in theirs home on 20th and Alder. Though not biologically related, Ted and Johnnie got along well, making the transition into his new family relatively easy. It was around this time that Ted changed his last name from Cowell to Bundy.

By all accounts, Bundy had a normal childhood. In her biographical account of Bundy, his co-worker from the National Suicide Hotline Ann Rule mentions that Bundy’s high school classmates thought of him as “well-liked and well-known.”

According to “America’s Serial Killers: Portraits in Evil,” when he was 14, however, a local girl, Ann Marie Burr, went missing from her home on 14th street and Junett. Bundy, who was the neighborhood paperboy, was rumored to be the assailant. Burr’s father claimed that he saw Bundy digging a hole in a construction site on the Puget Sound campus the morning Burr disappeared, stirring alarm that Bundy was involved in the kidnapping. Due to leads that traced Burr to Canada, this line of investigation was never formally pursued by the police. The case remains open, as no conclusive evidence has connected Bundy or anyone else to the crime.

Four years after the Burr disappearance, Bundy graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School and enrolled at the University of Puget Sound. Though school legend claims that Bundy either lived in Schiff or Anderson/Langdon, he actually lived with his family in their 20th street home.

Bundy’s collegiate career was sporadic, to say the least. After a year at Puget Sound, he transferred to the University of Washington (UW) at Seattle to study Chinese. He later dropped out and proceeded to work various minimum wage jobs across Seattle while volunteering on Nelson Rockefeller’s presidential campaign. His fervor for the campaign eventually lead to Bundy’s attending the 1970 Republican National Convention.

After briefly attending Temple University and later re-enrolling at UW, Bundy finally graduated with a degree in psychology. In 1973, he enrolled in the first class of University of Puget Sound Law School. Unfortunately, Bundy’s law school career was reflective of the rest of his college days; after only a year, he dropped out. Soon after, he found work as (ironically) the assistant director of the Seattle Crime Prevention Advisory Commission.

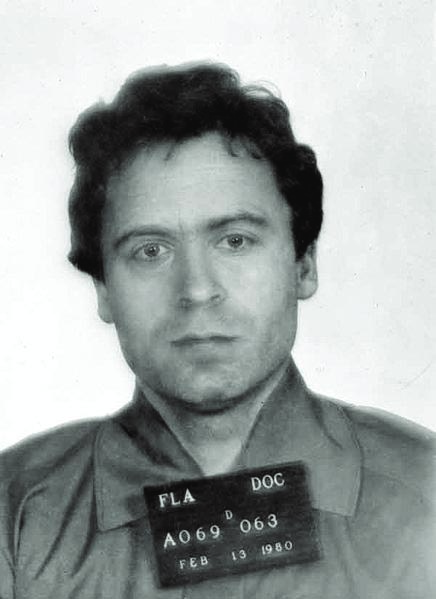

It was around this time that women started going missing from all over the Northwest. Though there is no confirmed first victim, the January 1974 kidnapping of University of Washington student Karen Sparks was at least the first attempted murder. Sparks, who was beaten unconscious in her apartment, managed to survive with severe permanent disabilities.

Later in February, Bundy broke into the apartment of Lynda Healy, another University of Washington student. Similarly, he beat her — this time to death — and dragged her body to his home to be buried.

Not long after these two incidents, Bundy’s tenure in the Northwest ended, as he moved between Colorado, Idaho and Utah, continuing on his binge of killings. To this day, there is no concrete number of how many people Bundy killed, though experts pin it around 30.

As generations pass, the Bundy name is fading from a household icon of the macabre to near folktale status. Archivists from the Tacoma Public Library note that “Bundy’s yearbooks had his photos torn out, as a souvenir of sort” but nowadays, they’re rarely even asked about him. For now, it seems that Tacoma has put the matter of Bundy to bed, and that, we’ll say is a good thing.