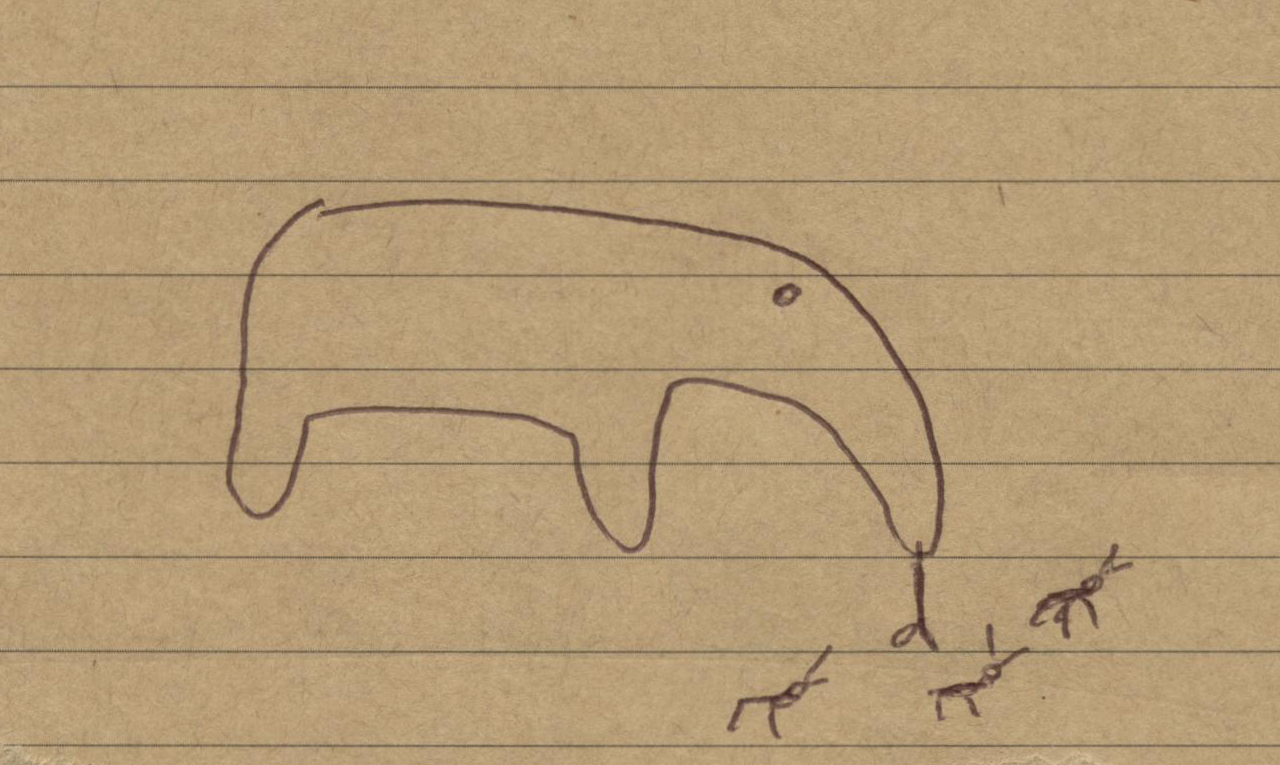

Here’s a challenge: draw the word “aardvark.” Now, ask the person sitting next to you to do the same. Chances are, your aardvark will look very different from theirs. According to Rob Angel, the inventor of the massively popular board game Pictionary, the same can be said of success.

In terms of success, what really matters, according to Angel, “is how you draw it, how you visualize it.” This was just one of many kernels of wisdom that Angel had to share during his lecture on Thursday, Sept. 20 in McIntyre 301.

Angel grew up in Spokane, Washington and graduated with a degree in business from Western Washington University in 1981. Soon after graduating college, he moved to Seattle, where he lived in a house with some close friends. Together, they came up with a wacky game involving sketching words out of the dictionary.

“We did it all night long,” Angel said. “Finally one night, after a few beers, I said, ‘This would make a good board game!’ Next morning, I remembered and they didn’t.”

In 1988, the LA Times published an article on Angel and his game, commemorating its 3 million copies sold. In the article, the Times attributed the game’s success to its simplicity: a game of charades in which instead of patomining clues, players draw them. Angel’s philosophy of business (and of life) is just as straightforward: Live openly, and live your intention.

The way Angel sees it, the idea for Pictionary had less to do with his own genius and more to do with the fact that he kept his mind open to the opportunities that surrounded him.

“I waited for Pictionary,” Angel said. “I really believe that — that the universe put Pictionary in my way. I was open to it and I was ready for it.”

That openness, as Angel described it, has a lot to do with how he interacted with the people around him.

“However you put yourself out there is gonna be what comes back,” he said. As such, Angel makes it a point to engage with others in an open and generous fashion.

“It doesn’t have to be big,” Angel said. “You can literally make an effort when you see somebody you don’t know, to just say hello. You don’t have to have a long conversation, just start taking those little steps.”

It is with the culmination of those little steps that you begin “getting rid of the judgement of yourself and other people.” That, Angel said, “opens up a lot. Because those experiences … start happening, that’s when the great stuff happens.” In fact, it was just such a moment of openness that brought Angel to campus in the first place.

It was Mandy Miller, the office administrator for the Asian Studies Program, who first met Angel on a plane to Denver seven weeks prior and struck up a conversation. “I’m very interested in people,” Miller said, “and I think a lot of people are not open. … When you are and you meet people, you can always learn something from everyone.”

The second ingredient to Angel’s success has to do with what he calls intention. “I lived my life for my intention. I can’t say this enough. Whatever your intention is for your life, be true to that. Not your goal. There’s a huge difference.”

According to Angel, goals are what you want to gain from life. Intention, on the other hand, is how you want to live it. Angel’s intention, for example, was to live for freedom.

“Every decision I’ve made since I was about 16 years old was based on freedom,” Angel said. “That’s all I’ve worked for my whole life: freedom to do what I want, when I want.”

Nobody, stressed Angel, can tell you what your intention should be. “Don’t let anybody else tell you what your vision is for yourself,” he said towards the end of his talk. “Just like the aardvark picture. It’s different than your neighbor’s.”

So what if your aardvark looks more like a tiny shrunken elephant, or a greyhound whose legs have been amputated in a horrible veterinary accident? Regardless of how it compares to other drawings, it is still your vision of an aardvark. And according to Angel, that counts for quite a bit.