Placed amidst warehouse buildings and set to a dramatic backdrop of the downtown Tacoma skyline and Mt. Rainier, sits the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC). The NWDC lies within four miles of campus, yet most students are unaware that behind a 20-foot-high fence detained immigrants await their immigration proceedings.

As Kelsee mentions, the topic of improving inclusion and understanding of undocumented immigrants on our campus is not a topic our campus wrestles with alone. Though it is easy to point blame at the campus administration, the issue of representation, inclusion and acceptance extends beyond our campus to the problems we face as a nation.

Contrary to popular belief—and stereotypes—the Pew Research Center found that in 2012 only 52 percent of undocumented immigrants in the United States came from Mexico.

While the number of immigrants from Mexico has been declining since 2009, immigrants from “Asia, the Caribbean, Central America and a grouping of countries in the Middle East, Africa and some other areas” has increased, according to the Pew Research Center.

Despite the rate of undocumented immigrants leveling out, the detention centers that hold individuals who have been detained and are going through immigration proceedings are reaching a highwater mark. The NWDC in Tacoma has experienced this, and has expanded a number of times in the past decade to cope with it.

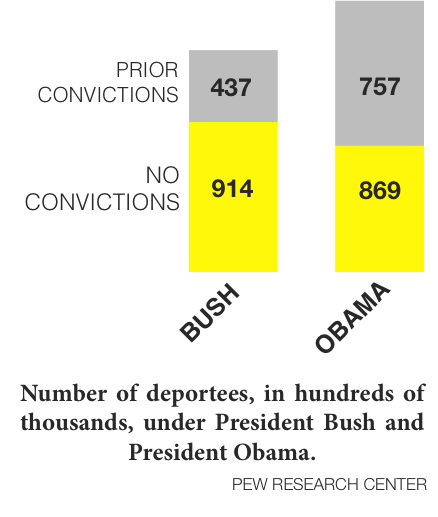

Indeed, under President Barack Obama, the number of undocumented immigrants deported has grown so high that some activists have called him the ‘deportation president.’

So what does it mean to be detained?

“Being in violation of immigration laws is not a crime,” the Detention Watch Network explains. “It is a civil violation for which immigrants go through a process to see whether they have a right to stay in the United States. Immigrants detained during this process are in non-criminal custody. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the agency responsible for detaining immigrants.”

Housing detained immigrants can cost up to $165 per person per day in such facilities as the NWDC, which at times hold young children and the elderly to avoid separating families.

The last count of the number of detained immigrants in the year 2012 was more than 429,000 according to the DHS.

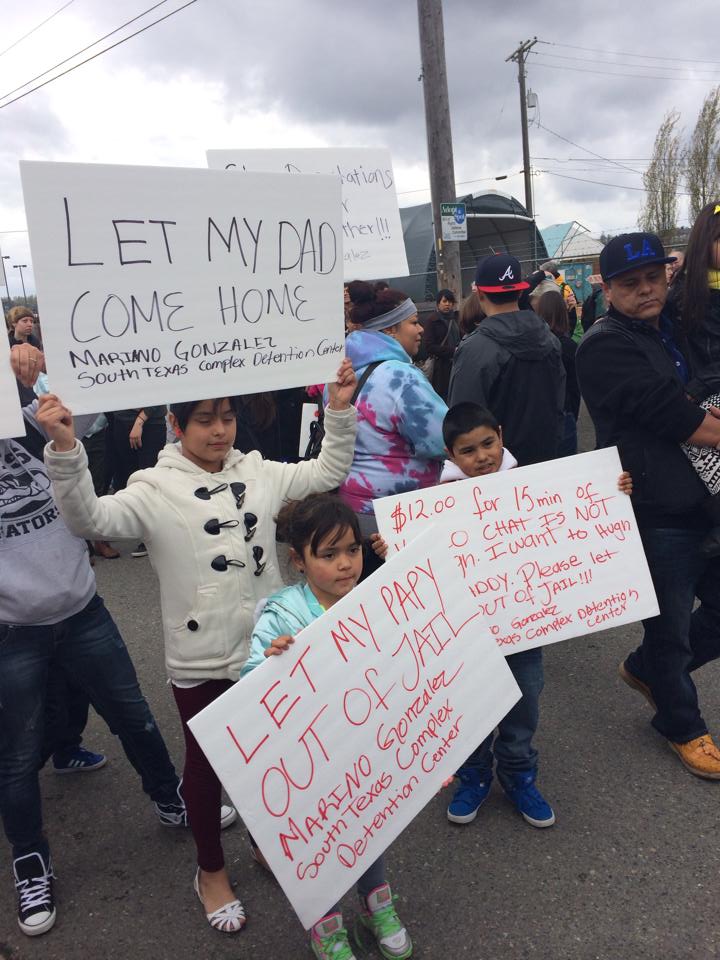

Groups such as Not One More Deportation, a national advocacy group, and the NWDC Resistence group, argue that detentions and deportations are inhumane and serve only to separate families, and that often innocent people are caught in the crosshairs of the law. Only about 45 percent of deportees have been convicted of a crime.

With only 250 facilities dedicated to holding detained immigrants, the DHS often turns to contracting private prisons. For the state of Washington, however, this approach has not been widely used. Opened in 2004, the Northwest Detention Center has held the majority of detained immigrants in the northwest region of the United States.

With only 250 facilities dedicated to holding detained immigrants, the DHS often turns to contracting private prisons. For the state of Washington, however, this approach has not been widely used. Opened in 2004, the Northwest Detention Center has held the majority of detained immigrants in the northwest region of the United States.

“Since the NWDC opened, the number of individuals detained has continually increased just as the nation’s detention population has increased. In the first four months of its operation from April to July 2004, NWDC admitted 1,855 individuals into the facility. Over the next 12 months, NWDC admitted 6,456 individuals. From June 2006 to June 2007 the number grew to 8,849,” a report from the Seattle University School of Law explained in its 2008 study “Voices from Detention.”

Similarly to the University of Puget Sound and undocumented immigrants finding representation on campus, detainees struggle to find legal representation in detention centers.

The report cited one attorney representing detainees at the NWDC, whose only given name was Davis.

“The time used traveling to Tacoma and waiting at the detention center adds a lot of cost to detention cases. This high cost deters potential clients from seeking representation by [his] firm,” the report said.

Without proper representation, the detainee cannot gain the knowledge or counsel necessary to fully understand their situation, nor are they aware of all the legal options available to them. Detentions can range from the average of 35 days, to one detainee’s eight years. That detainee spent four years at the NWDC after being transferred from another facility.

The lack of representation does not only fall on the shoulders of the administration of the NWDC, which is owned by the GEO Group (a private organization that owns over 100 prisons around the world) but also the DHS. All of these organizations have rules in place that, in theory, should protect detainees from human rights violations.

Despite this, the NWDC has been the focus of at least one lawsuit by the ACLU accusing the NWDC of attempting reprisals on detainees who organized a hunger strike, a lawsuit that was later dropped.

The NWDC has also been accused of providing inadequate access to medical care (especially emergency care), insufficient quality and quantity of food to maintain detainee health, inadequate treatment of the mentally ill (including the use of controversial solitary confinement) and hindrances to the acquisition of fair representation.

Though the NWDC states that they undergo rigorous inspections by the DHS and that they contract monthly inspections to an outside company, these violations clearly highlight that there are not enough checks and balances to ensure the humane treatment of detainees in and out of the centers.

Change can start at the ground level with the facility, or from the top with the DHS enacting stricter rules and surveillance. As another article has mentioned in this issue featuring undocumented immigrants, Kelsee Levey’s radio show is attempting to start from the bottom.

Her radio show starts from the ground level by divulging detainees’ stories for those outside the center to hear. This provides undocumented immigrants with the opportunity to speak to the public to enact change beyond the walls of the detention center.

Detainees have gone on multiple hunger strikes over the past two years to protest their unfair quarters and the alleged ill treatment they receive. These strikes attempt to reach out to anyone willing listen in order to improve the living conditions at the NWDC.

With the GEO group contract extended until another prison contractor buys the NWDC, it is now more important than ever for their voices to be heard and acted upon.