On the same evening as the biannual Take Back the Night march against sexual assault, activist Jaha Dukureh’s Nov. 7 visit broadened the campus discussion to one of international women’s rights. Dukureh is the first African UN Women Goodwill Ambassador and a 2018 Nobel Peace Prize nominee for her work to end female genital mutilation (FGM), which she covered in her talk “A Survivor’s Journey to Ending FGM.”

Dukureh’s lecture discussed the steps that she and her organization, Safe Hands for Girls, are taking to end FGM and child marriage around the world. Students gathered again later that night for the Take Back the Night march.

According to the World Health Organization’s website, FGM is a procedure of intentionally altering and injuring female genitals for non-medical reasons. Problems that result from FGM range from extreme discomfort during sex to death due to severe bleeding.

Before she began her talk, Dukureh showed a short documentary about the history of her activism. The 20-minute video tells the story of how one petition turned into a global campaign, an international organization and tangible change in the Gambia and other countries.

After the video, Dukureh began by sharing her motives for speaking out against FGM and child marriage practices by connecting them with her own past. She is a survivor of both FGM and child marriage, having been married at 15.

“What happened to me, I didn’t want to see any more girls go through that experience. As a result of that, I started to speak up. When I started talking about these issues, I never in a million years thought that I would be standing in front of you or that the world would get to know who I am through my work,” Dukureh said.

Her global-scale efforts began four years ago in 2014 when she saw a petition from London to end FGM and decided to create her own.

Dukureh’s petition gained over 220,000 signatures, which brought it to the attention of leaders such as President Obama, who ordered the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to conduct a study on the issue. The CDC found that more than half a million girls in the U.S. alone go through FGM every year.

Dukureh’s work continued in 2015 when she returned to her home country of The Gambia and followed the country’s president, Yahya Jammeh, on his political tour. After she got the chance to speak to him and his cabinet, Jammeh issued a historic statement that banned the long-held practice of FGM in the country.

Dukureh explained that her organization is tackling the problem from many different angles, but she explained that the most important aspect was severing the connection of FGM practices with religion.

“We work with religious leaders and try to convince them that this is not in the Qur’an, it’s not in the Bible, it’s not in the Torah,” she said.

“It’s something that’s brought by culture, but culture changes. Looking at the U.S. for instance, slavery was a culture in this country. For us to be able to move past that shows that culture is not one thing and culture is not stagnant,” she said.

Dukureh also talked about the value of individual voices, specifically the voices of survivors of FGM and child marriage, in creating change.

“I’m using my own story as an example and showing a lot of these young women that were forced to get married at such an early age that they too can make it out of whatever situation they’re in. … We believe that in sharing our stories, it’s not only about ending the practice but about healing ourselves in the process,” she said.

Dukureh talked about the fact that her work comes with a lot of risks, particularly when she confronted President Jammeh about FGM practices in The Gambia. She recognized Jammeh as a feared dictator and went into her work fully aware of the risk involved.

“If I tried to talk to the president of Gambia, one of two things would happen — I would either end up dead or I would get what I wanted,” she said. Though in that case, the latter was the final result, Dukureh acknowledged the danger that persists for her today, consisting of insults and death threats to her and her family.

Although her work has greatly affected her safety, Dukureh expressed how important it is that she doesn’t stop advocating for these rights.

“I believed in doing the right thing. I knew that even if I ended up dead, there would be a lot of people all over the world that would stand up and say something. When you look throughout history, there were always people who stood up for what they believed, and some died as a result of that, but because of their courage, a lot of things changed after them,” Dukureh said.

Dukureh and Safe Hands for Girls aim to have FGM and child marriage banned everywhere by 2020 and to have these practices eradicated by 2030. Until then, Dukureh and her team will continue visiting cities across the country and around the world to spread their message and to spread awareness.

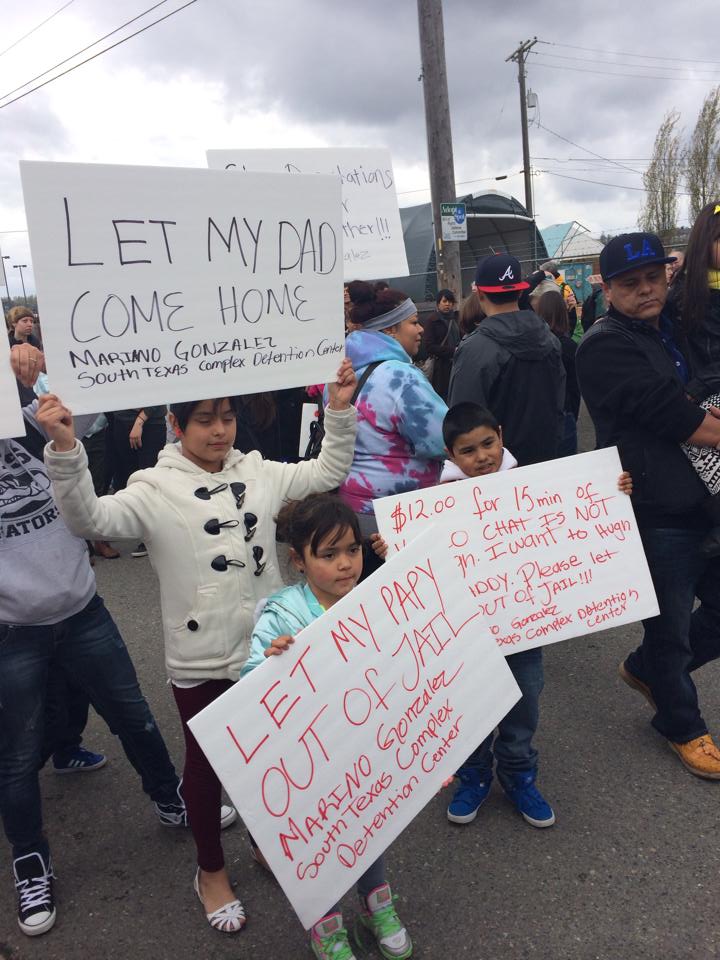

The Take Back the Night march later that night promoted similar themes of self-advocacy and survivor-led change. About 20 students carried posters, chant sheets and electric candles as they marched. The group spread messages of hope, safety and empowerment throughout Union Street, 6th Avenue, and Alder Street.

The event was organized by B.R.A.Ve (Bystander Revolution Against Violence) as part of a long-standing tradition on this campus, and on college campuses around the world. Take Back the Night marches and events began in the 1970s intended as direct action against domestic violence and rape.

Though the group was smaller than previous years, they exhibited no less power and energy. They prompted bystanders to come out of their homes and join them with chants like this: “End it, end it, end the silence! Stop it, stop it, stop the violence!”

The group continued the event with an open discussion in the Rotunda after the march. The space was provided for survivors of assault and allies to share their experiences and feelings, and offer support where it was needed.

Dukureh offered an empowering sentiment in her talk about how individuals can approach these issues and begin to solve them.

“You don’t have to know what the practice is, but you can educate someone, you can learn more about it,” Dukureh said. “We can continue to raise awareness to make sure this ends within our lifetime. I believe that our moral obligation as human beings is to start caring more about not what’s happening around us, but what’s happening in the world.”