Maybe you’ve always looked at your genitalia and thought, “Yep! Seems right!” Maybe you thought, “Not really my style, but we’ll make it work.” Maybe instead you proclaimed, “I am not defined by my genitalia!” But what if your genitalia doesn’t fit into our binary system of female or male?

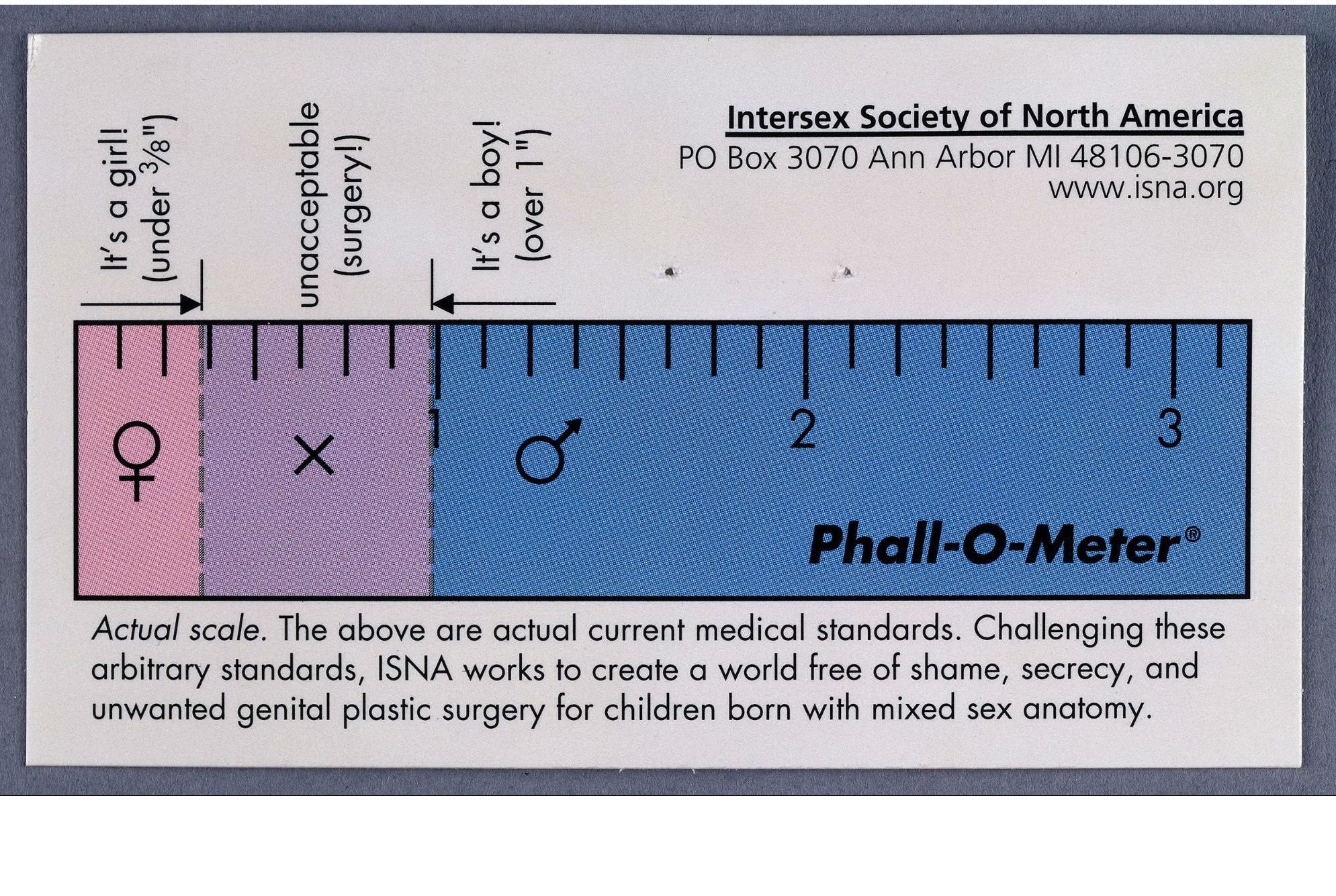

According to the Intersex Society of North America (ISNA), the term “intersex” refers to “a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male.” Intersex occurs when the chromosomes of an individual do not perfectly line up while the fetus is developing, and displays itself in many ways, some physical and others not. Intersexuality refers to anyone whose genitalia and/or biology varies from the boundaries of normalcy defined by society.

There are many conditions for which intersex may apply, including Klinefelter Syndrome, which is a deficiency of testosterone in men, and Turner Syndrome, in which women lack an X chromosome. Some people may be born with mosaic chromosomes, where some cells contain XX chromosomes (female) and some contain XY chromosomes (male).

Intersex is not uncommon. In statistics procured by ISNA, approximately 1 in 100 people’s “bodies differ from standard male and female.” These numbers are exceedingly difficult to examine because of the varying definitions of what counts as intersex and what doesn’t.

Throughout history, intersex people have faced many hardships, both socially and within the realm of science. Initially, intersex people were referred to as “hermaphrodites,” as coined by Greek physician Hippocrates. This term, however, implies that “a person is fully male and fully female,” as explained by ISNA. In the early 20th century, this term was replaced by “intersex.”

As the field of medicine grew, many physicians believed in using medicine to align ambiguous genitalia to the gender binary. In the 1950s, Johns Hopkins University became the first to medicalize intersex treatment with a process that functioned to eliminate intersexuality in early childhood through surgery, endocrinology (hormonal treatments) and psychology. Many believed that large clitorises or small testes, both common attributes of intersex, would lead to homosexuality. In medically altering genitalia, doctors hoped that people born intersex would end up heterosexual, and therefore “normal” by societal terms. Throughout the century, this treatment was the standard for children born intersex.

Such action did not come without consequences. A stout believer in the Hopkins method was Dr. John Money, a psychologist who argued that gender was largely fluid throughout childhood. Such claims were based upon patient David Reimer, born male (not intersex), who suffered a botched circumcision which ended in a gender reassignment surgery. Raised a female, Reimer seemed a “successful” patient: i.e., not homosexual.

However, Reimer endured years of body dysmorphia and other psychological torment. In his biography, “As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl,” written by John Colapinto, Reimer illustrates the sexual mistreatment endured by him and his twin brother on behalf of Dr. Money in efforts to prove his heterosexuality as a child. Having never fit in to his identity as female, Reimer transitioned back to being a man once he learned about his past at age 14. In 2004, Reimer took his own life at the age of 38.

In the years following Money’s argument that doctors should realign intersex children due to the malleability of gender, few proposed counterarguments. Parents were told their LGBTQ+ children would grow up “normal.”

Change came in 1993, when Dr. Anne Fausto-Sterling wrote several articles on gender and biology, most notably “The Five Sexes: Why Male and Female Are Not Enough.” This article sparked a movement for intersex rights, and ISNA was founded by Cheryl Chase the same year.

Intersex activists have dramatically influenced the medical field, and many doctors today do not treat intersex as a medical condition worthy of treatment or “correction.” As the movement has grown, its goal of having intersex people recognized as perfectly normal people has slowly intermingled with the LGBTQ+ movement. The fight for bodily autonomy, particularly with respect to genitalia, has become increasingly included in modern-day civil rights movements.