Dedicated to the memory of both important events and peoples of the history of the African diaspora, Black History Month propagates celebration and remembrance of black history. Here on campus, there have been many events surrounding this national month of remembrance and appreciation.

Each of these events has been presented through a different medium, including poetry, spoken word, a classic blues and jazz concert and more. Melanie Herzog, a professor from Edgewood College in Madison, Wis., gave a lecture on Feb. 2 specifically about the art and works of Elizabeth Catlett.

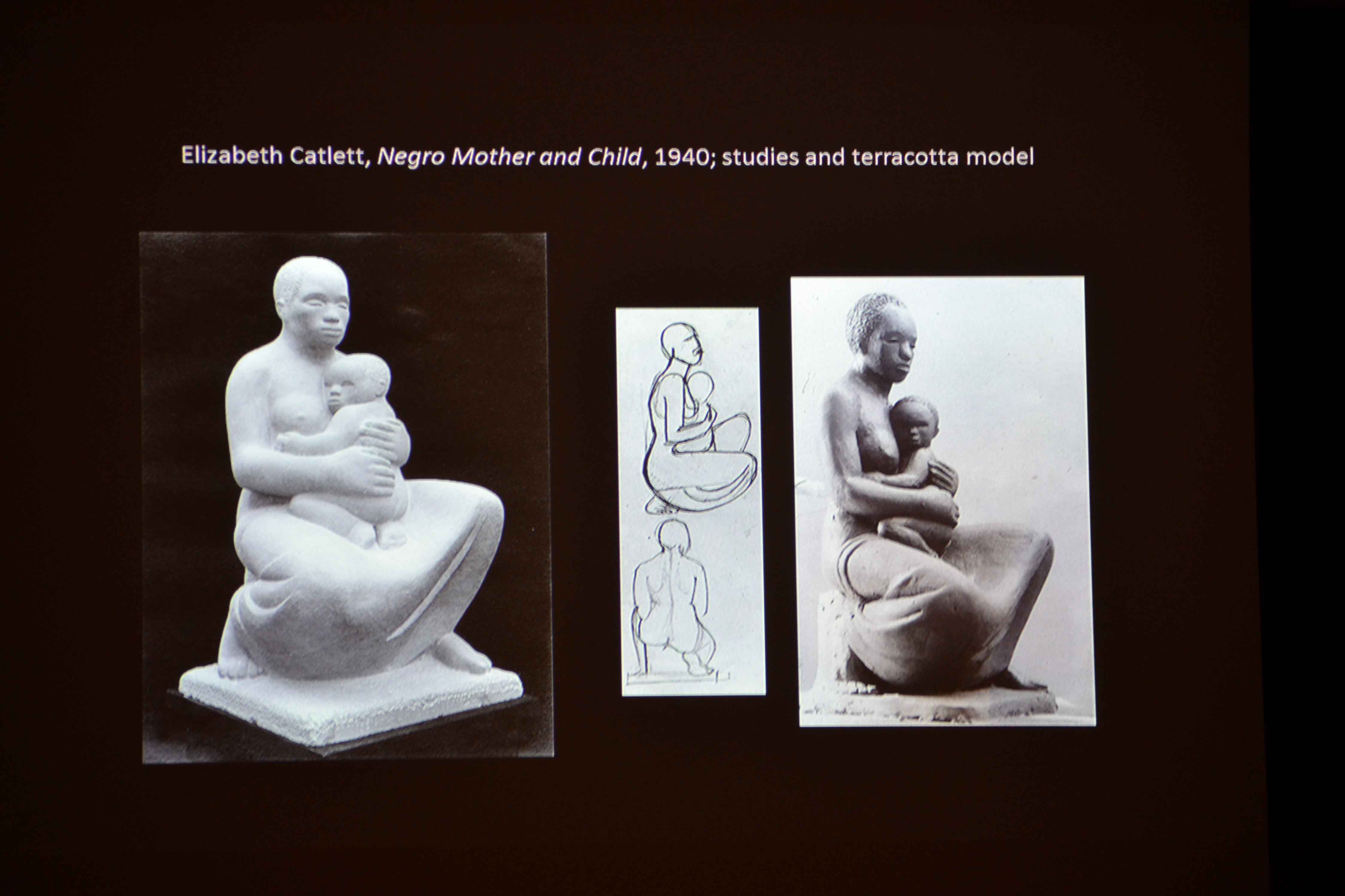

Herzog’s lecture, presented in a beautiful slideshow of images of Catlett’s work, discussed Catlett’s life from start to finish and various influences on her artwork. Known for prints and sculpture, Catlett combined characteristics of both Mexican and African artwork—and, in another way, abstract and realist styles, accrediting her abstract influences to traditional African and Latin American art. She worked with many different mediums, including wood, metal, stone, linoleum and watercolor, tempera and oil paints.

Central topics of Catlett’s artwork include the relationship between mother and child, the suffering of the impoverished, unequal opportunity for African Americans and later, Mexican children and the recent revolution.

In everything she created, Catlett drew from personal experience and believed that people could only connect with art that resembled them.

For instance, her first sculpture in stone, a more realist work entitled “Negro Mother and Child” (1940), emphasized the importance of black motherhood. In a sense, the piece is a reflection of who she is, transcending simply the label of “artist” —as a black woman and mother, it resonated deeply with her personal and cultural identity.

She sculpted women because she is a woman, and moreover, a black woman in America. The piece, created for her senior thesis at the University of Iowa, resulted in her reception of a Master of Fine Arts—one of the first students and African American women to receive one. The “Negro Mother and Child” went on to be presented at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago, where she first gained fame.

Shortly after the Exposition, Catlett began to increasingly entertain the influences of abstract art. Making another set of sculptures, similarly entitled “Mother and Child” (1942-1944), she combined aspects of both realist and abstract art.

She initially worried how audiences would receive these works, as she still focused on the idea that they could more easily relate to artwork that resembled themselves or their lives in some way. However, her new incorporation of abstract influences became a medium of expression—she was able to reflect the curves of a body, the fluid and almost singular form of a mother holding a child and even more so able to represent the identities which she strove to depict.

In 1946, Catlett moved to Mexico, drawn by the murals and sculpture that came out of the Mexican Revolution. She soon became fascinated with the Mexican identity, and inspired by prints from the Mexican Revolution, created “I am the Negro Woman” (1946-1947). In this work, she used texture in order to portray meaning and further the message of her work.

She also created prints of Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, combining aspects of Mexican print with iconic African American figures: an American subject with Mexican stylings. In this way, she connected with both Mexican and African American audiences—both were able to relate to her works and find meaning within its subjects.

Another good example of this hybrid artwork can be seen in “Civil Rights Congress” (1949), a seamless blend of Mexican and African American topics. In this piece, an African American judge and child can be seen, paired with a hybrid Klu Klux Klan-Spanish skeleton, a cross and a noose. As was her intention, the work spoke to both communities.

Returning to her more primary subjects of art, the African American identity, she created works such as “Homage to My Young Black Sisters.” Based off of the iconic raised fist demonstrated by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, it depicts the somewhat abstract figure of a woman raising her fist as a symbol of pride and strength. Catlett used wood in order to accentuate the “brownness” of the figure, and additionally, to emphasize the curves of a woman.

“She sculpted women of agency,” Herzog said. “They are independent and dignified.”

Catlett’s most famous final work, shortly preceding her death in April of 2012, was the 10-foot bronze statue of Mahalia Jackson, a famous black Gospel singer known for her civil rights activism and her power and influence as a black woman. In this work, Catlett’s various influences shine through the statue’s bronze curves, upheld hands of strength and movement, the abstract aspects of her flowing clothes and the realist qualities in her face and stature.