The Black Student Union and KUPS presented the first of a film series dedicated to black musicians in Rausch Auditorium. This first film, Wheedle’s Groove, showed the rich history of the soul music scene in Seattle during the 60s, which was soon forgotten by the rising popularity of disco in the 70s.

Luckily, local DJ and record collector, Mr. Supreme, rediscovered many of these soul records. Mr. Supreme’s findings supplied much of the movie’s content, especially its focus on particular Seattle-based music groups. The members of these since broken-up bands were interviewed in the movie years after their music had been popular.

The 60s started Seattle’s reputation as a city with a thriving music scene, and this music included, at first, jazz.

“We were all influenced by jazz,” said Herman Brown, who was a guitarist of the band Cooking Bag (1967-1973).

Jazz eventually led to soul, which led to R&B, funk and the like. The spread of soul, while certainly prevalent throughout all of Seattle, planted its roots in the large black population of Seattle located in the Central District, more commonly known as the CD.

“There’s still a warp in [CD] that I don’t feel anywhere else in the city,” Reverend Patrinell Staten Wright, who sang gospel music in church before becoming a popular soul musician herself, said.

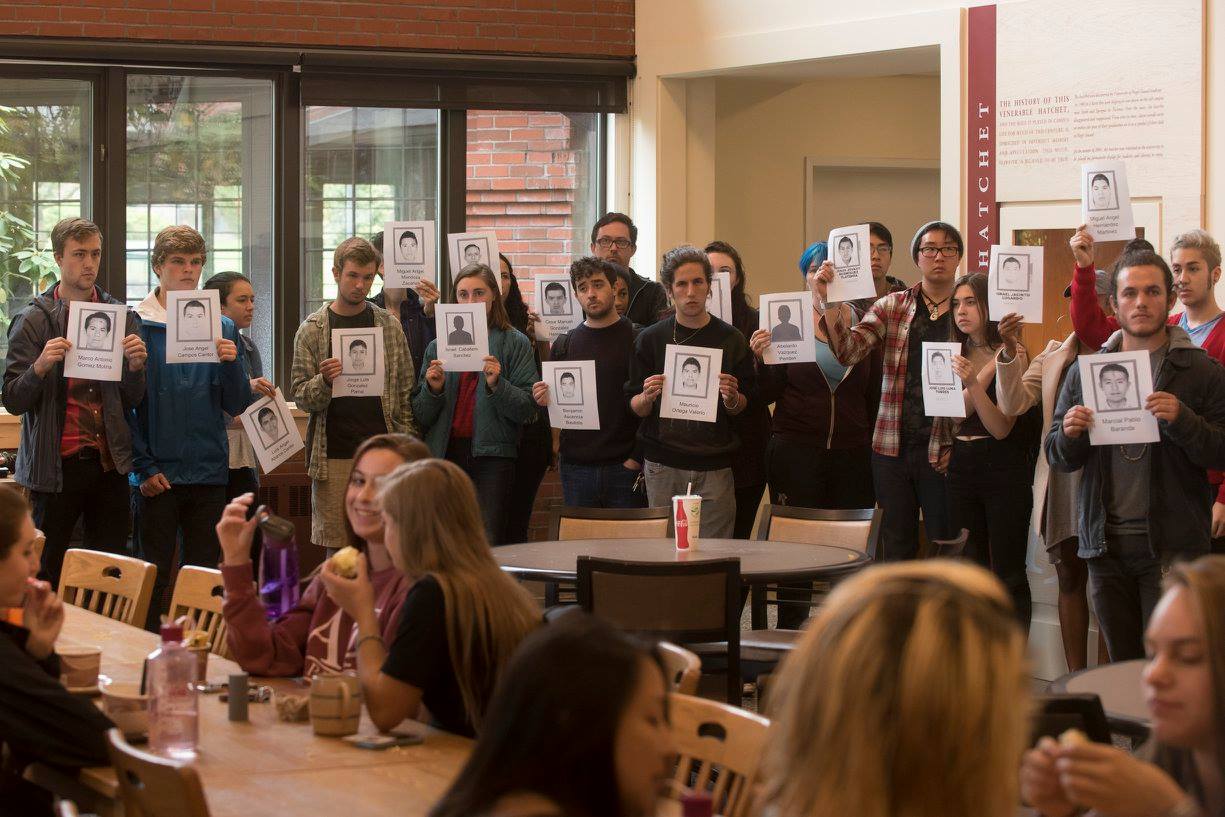

Another great influence during this time period was the Civil Rights Movement. The movie focuses on a certain event in which members of the Seattle Area Black Student Union led students in a sit-in at Franklin High School, protesting the expulsion of two black students who wore their hair in “natural” hairstyles, which was considered unmannerly by the school’s administration.

While the Civil Rights Movement made great leaps in racial equality, neither the fact that racism was still very prevalent through the United States, nor that it affected black musicians, can be ignored.

For example, the band Black & White Affair, was considered “black” band, given that they were made up of mainly black musicians. The same was the case with Cold, Bold, & Together, a band also consisting mostly of black musicians as well as a white and an Asian musician.

Being a black musician or band during this time made it harder to make a living, as many musicians commented. More money was offered in clubs to white musicians, and even if a song by a black musician got to the top of the charts, this did not guarantee a steady income.

The white members of Black & White Affair and Cold, Bold & Together—particularly Kenny G of Cold, Bold, & Together—mentioned that they could get into places their fellow black musicians could not.

The band members themselves were “color blind,” not caring what race the musicians were so long as they were talented. But the hirers were less so. There were still many separated black and white clubs in Seattle during this time.

Despite the racial inequality of the 60s, soul musicians of all ethnicities flourished in Seattle, at least until the emergence of disco in 1975. However, perhaps big hair and platform shoes were not the only factors that pushed the soul music scene out of Seattle.

“Seattle has never been a place where you can make it big,” said one musician. “Jimi Hendrix came from Seattle, but he had to leave Seattle.”

“Seattle is a place that, for a musician, you want to leave,” said Philip Woo of Cold, Bold, & Together. He added that Seattle is “so far away from everything else,” which is not necessarily advantageous for musicians who want to make it big.

Many of the musicians, including Kenny G, commented that they did not necessarily want to leave their bands, just that there were better opportunities in bigger cities such as Los Angeles.

As a result, many soul bands broke up by the end of the 60s, both ending the time for soul and allowing other music genres to become popular in Seattle, such as disco in the 70s and grunge in the 90s.

However, the musicians emphasized that their careers began in Seattle and, were it not for that start, they wouldn’t be the successful musicians they later came to be.

Movies like Wheedle’s Groove help to preserve the history and the beginnings of music. The bands featured in the movie may no longer be popular, but they likely paved the way for much of today’s music, and this movie remembers and appreciates those beginnings 50 years later.

PHOTO COURTESY / MICHAEL VILLASENOR