By Kylie Gurewitz and Julia Schiff

“How can I be a force of compassion and belonging in groups?” This is the question that lawyer, writer and Seattle University professor of law Dean Spade invited Puget Sound students to ask themselves at his workshop.

On Feb. 19, Dean Spade visited campus to lead a workshop titled “Getting Together, Tearing it Apart: An Interactive Workshop about Radical Relationality in Campus Activism” and give a lecture called “Queer and Trans Survival and Resistance in Scary Times.” Spade’s visit was sponsored by the John Dolliver National Endowment for the Humanities Endowed Professorship, the Department of Gender and Queer Studies, the Center for Intercultural and Civic Engagement and the Associated Students of Puget Sound.

In 2002, Spade founded the Sylvia Rivera law project, a “collective organization focused on providing free legal services, engaging in impact litigation and building community organizing led by and for trans and gender nonconforming people who are low-income and/or people of color,” according to Spade’s website.

Other projects of his include the Big Door Brigade (a collection of mutual aid resources for a broad range of issues), No New Youth Jail (a website documenting the activist work against the youth jail in Seattle), “Queer Dreams and Nonprofit Blues” (a video series about nonprofits and activists) and “Pinkwashing Exposed” (a documentary on Palestine solidarity).

Spade’s “Getting Together, Tearing it Apart” workshop focused on building and leading social movements, both broadly and specifically, and thinking about campus activism. Spade’s career of working within social movements around transgender rights, prison abolition, Palestine solidarity and anti-racism informed the workshop’s understanding of broad social movements, and his work as a professor informed the campus activism focus.

The workshop began with a discussion of what makes a social movement effective and what makes a leader effective. According to Spade, “leaders are people whose visions involve a lot of people and compel a lot of people.”

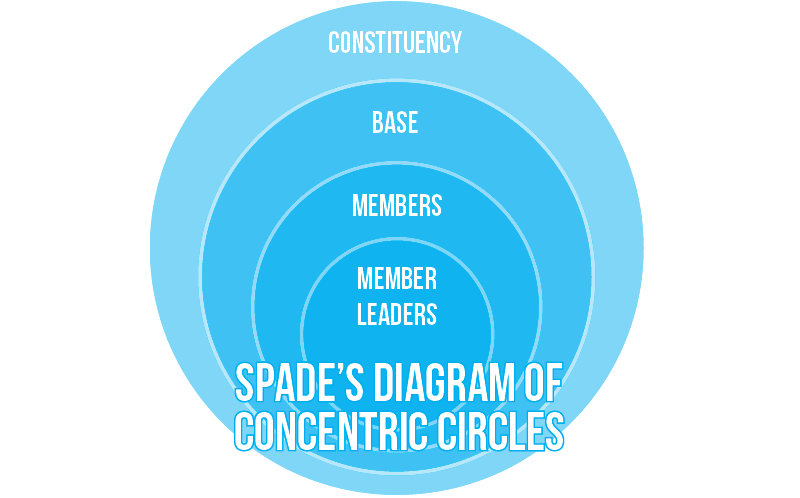

One of the main ideas of the workshop was the importance of bringing more and more people into social movements. Spade discussed the idea of base-building: expanding the amount of people you can bring into your social movements.

This led into the next part of the workshop, which included a diagram of four concentric circles; from the outside moving in they were labeled constituency, base, members and member leaders. The idea of this image is to keep moving people in toward the center circles, so that the people in the constituency become the base of the movement, the people in the base become members and those members become leaders. Spade emphasized that as a leader of a social movement, one should never blame people for not showing up for the movement but rather ask oneself how to do a better job of bringing people in.

The workshop then split into smaller groups to discuss how these concepts played out in students’ personal experiences of activism and social movements. The group discussed the barriers to showing up for events and meetings and the mobilizers, how it feels to show up for movements, and how it feels to stay home.

Coming back into the larger group for discussion, the main barriers to showing up were identified as not having anyone to go with, fear of taking up space, wondering if it matters, feeling the content will be boring, fear of conflict and feeling self-critical.

The main mobilizers for showing up were having people to go with, good weather, making a sign first, having a feeling of excitement or urgency, feeling necessary or needed at an event and viewing that event as fun or cool.

Spade explored some of these mobilizers that initially seemed comical or silly, such as having a sign first. He discussed how outwardly representing your views, especially at an event that you might not feel fully aligned with, can be a powerful mobilizer.

Later in the day members of the campus community gathered to hear Dean Spade discuss activism in the current political climate. “The law is horrifying; it was designed to be that way,” Spade said, pointing out the current state of oppression and inequality in the United States. He focused mostly on the concept of mutual aid, and how long-term, collaborative engagement in helping one another is revolutionary.

He began his speech by acknowledging the United States’ history of colonialism, saying that our current state has been built off of the backs of the oppressed.

He divided his speech into a few main sections, looking at the history of advocacy and what productive advocacy means.

“Most of us are not invited to do much critical thinking about the pitfalls of reform,” Spade said, trying to get the audience to understand that reforms aiming to help can actually hurt.

He addressed the concept of non-profitization, seeing it as a form of contained progress that stifles productive change. Spade understands nonprofit work as an inadequate representation of democracy. According to him, it takes away from a communal approach to advocacy.

Nonprofit work gives issues owners, forcing competition between advocates who have similar goals. Money, or the competition for grants, makes nonprofits work against each other for funds. According to Spade, nonprofits are another arm of an oppressive system, as they have set an ineffective standard for advocacy. Further, this standard has stigmatized previous movements like the Black Panthers, forcing advocacy to look a certain way.

He prompted the audience to interrogate current forms of advocacy and activism. His main questions to ask are: Does it mobilize? Does it break social norms and relations? Does it have elite support? If a movement effectively mobilizes people and breaks social norms and relations, it might have teeth. However, if a movement has elite support, it may not be the most effective.

He focused productive advocacy on the concept of mutual aid. Mutual aid, according to Spade, means building safety and structures of support for the disenfranchised and forming meaningful systems of communication between people. To be an effective practitioner of mutual aid, one must have “humility and ability to receive feedback,” Spade said.

Long-term commitment, dedication to conflict resolution within the community and ridding oneself of the “savior complex” are also crucial. Finally, consensus-based decision-making is essential. According to Spade, majority-based decision making leaves people feeling unheard and forgotten. Consensus represents a community-oriented and receptive approach to action.

Some examples of mutual aid projects are the Oakland Power Projects and jail support programs such as Black and Pink.

The Oakland Power Projects work to engage community members in supporting one another in times of crisis to avoid police involvement. Police represent a threat to many communities in Oakland, so community support and organization is a way to remain safe without the added threat of police, according to Spade.

Inmate support programs such as Black and Pink are also examples of mutual aid. They set up at-risk inmates with pen pals from outside of prison. This small act of support builds community, fostering an atmosphere of support for people subjected to loneliness and disenfranchisement by the system.

Spade emphasized that long-term acts that help in alleviating the everyday burden of the disenfranchised are most effective. Helping to build communities of support and mutual caring are the most effective methods of advocacy.

Elena Staver, a junior at Puget Sound, attended the talk, not knowing about Spade’s work. She showed up because her friends had helped organize the speech and workshop.

“I was curious; I’m always excited to go to talks about systems of oppression and ideas about resistance,” Staver said.

Spade’s speech was inspirational, according to Staver. “I am motivated to become more involved in anti-racist and anti-system work,” she said. “This talk has given me some interesting theoretical conceptualizations to then base action off of,” Staver said.

In the question and answer portion of the talk, one student asked how Spade remains hopeful during this time, in the work that he is doing. He answered that “hope is a practice.” People doing this type of work must practice hope and optimism; it is not an easy thing. “I plan to die fighting,” Spade said.