The Race and Pedagogy National Conference (RPNC) sparked endless important discussions about race, social activism and our part as students and educators in it all. We have been inspired by learning about activism in the past and look forward to disrupting the status quo in the future. But what if our narrative of how activism and movements actually work is constrained or even convoluted?

Alicia Garza, co-founder of the Black Lives Matter project and final keynote presenter at the conference, made this point in her speech at the Fieldhouse: a movement doesn’t start from a hashtag. While #BlackLivesMatter became a worldwide phenomenon via social media, Garza held that the power that came from the movement didn’t stem at all from a clever hashtag, but instead from years of toil through community organizing and outreach.

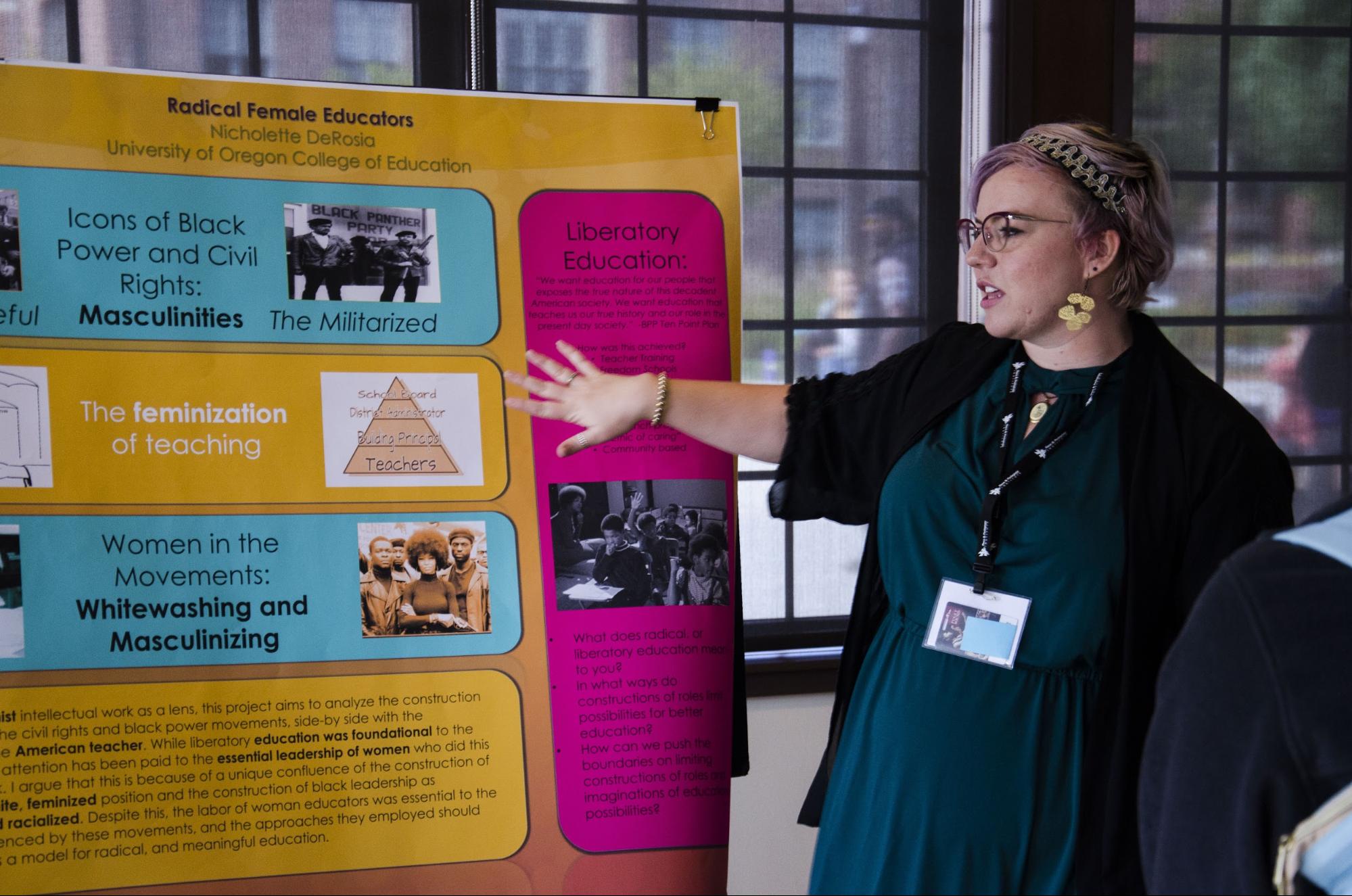

University of Oregon doctoral student Nicholette DeRosia wants the U.S. to reexamine how we look at racial activism. DeRosia presented her research on education called “Radical Female Educators” at RPNC on Saturday. She said that she took an ethnic studies course late in her academic career and was shocked to find that in all of her previous education she hadn’t learned about the countless female civil rights leaders that did much of the work behind the Black Panthers. She decided to launch a research project about how educators present civil rights activism history.

In her research, she found that we speak about Black Power groups as almost fully male, and even masculinize the few women that are shown to be part of the work. DeRosia also found that we especially focus on the violent aspects of this movement even though a lot of Black Panthers’ work, for example, were in communities involving adult literacy programs and child care.

“Women did most of this work,” DeRosia said, “But it isn’t depicted by educators that way. Women are shown as either soft feminine teachers or masculine and violent and nothing in between.”

In her work, DeRosia compared charts of the hierarchy of U.S. Christian patriarchy with educational hierarchies. She listed “Christ” at the top of the patriarchy list, with “Husband” in the middle and “Wife” on the bottom. In the education hierarchy, she listed “School Board” on the top, then “Principal,” then “Teacher.” DeRosia found in this comparison as well as in her other research about educators that we see teaching as an extension of motherhood. This makes our idea of teaching an inherently feminine one.

“Women’s work in activism has been revolutionary. It should not be based in patriarchal views,” DeRosia said. “Sadly, this is still how we view activism today.”

“The way we talk about these things matters. If we construct activists as only masculine figures and teachers as only motherly figures, we are not doing justice to how activism work has played out historically,” DeRosia said.

Just like Garza implied that her and her co-organizers’ years of activism work was not recognized as the fuel for the hashtag they created, DeRosia holds that much of women’s work in activism is not recognized by educators when teaching their students about social movements. How can this change?

“It’s time to add names like Assata Shakur and Fredricka Newton to our curriculum about activism,” DeRosia said. “And encourage women to claim credit for the revolutionary work that they do.” These women, both radical members of the black liberation movement, played a crucial role in history.