By Eada Gendelman

Nikita

For fifth-year student Nikita New, education was never a given. Her mother grew up in El Salvador during the Salvadorian Civil War and was forced to drop out of school in the ninth grade. Her father was also raised in an unsafe and poverty-stricken environment where getting an education did not seem feasible. Although 42 percent of students whose parents attended college usually graduate within four years, only 27 percent of first-generation students graduate within the same amount of time, a 2011 University of California Los Angeles study revealed. Given this fact, New spent her entire young life wondering whether or not she would have the chance to complete college.

New grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and despite both of her parents working full-time, her family always struggled with money. Her mother worked as a nanny for several wealthy families, including those of politicians. These families ended up being very invested in New’s life and played a large role in her decision to pursue higher education.

“I don’t think I would have ever thought about going to college if it weren’t for the other adults in my life that really convinced me it was an option,” New said.

New believes that she got very lucky when it came to the people she was surrounded with during her youth. Through her mom’s job, she was able to attend a high school outside of her district, where she was provided with resources that she wouldn’t have had otherwise.

“Because the school was so wealthy, I was given access to materials that my home high school could not offer me,” New said. “I’m very thankful I went to school there because I was always surrounded [by] people who really valued education.”

Although New’s school provided her with many opportunities, it also made her realize just how different she was from her peers. In contrast to the wealthy, white majority at her high school, New came from a Latina background and a lower economic status, lacking the same academic support system as most of her friends.

“I saw parents invested in their children’s educations in ways that my parents couldn’t,” New said. “There are many study tools that I am now lacking, and there are many concentration issues that I now struggle with, because I wasn’t ever disciplined to do my school work. I didn’t have role models to show me how to do these things.”

New struggled with homework because her parents didn’t understand the material and couldn’t offer their help. When it came to applying for college, New had to ask counselor after counselor for instructions and advice. Additionally, when it came to paying for higher education, New was completely on her own.

“I had to put a lot of extra hours into scholarships, and I’ve been working since I was 11 years old, just saving up money,” New said. “It’s been really hard paying for school, but I knew that I would do whatever it takes.”

Even after completing four and a half years of college, New still struggles with the difficulties of being a first generation student.

“It’s embarrassing to admit that I don’t have the same skills as others. I am proud of myself for getting through college, and it makes me feel like I am equal to everybody else here, but there are times where I have to admit that I need extra help,” New said.

Because of her background, New believes she has a certain appreciation for education that others may not. Throughout her time at the University, she has been in situations that made her feel discouraged and even unsafe, but she doesn’t let it stop her. She feels very lucky to be in school.

“I value education so greatly because many of my family members want to attend college and they can’t,” New said.

New says that part of the reason she has been able to accomplish so much is because of her passion and her drive, but more than anything, she believes that she owes her success to the people who helped her make this happen.

“It’s hard to ask for help, because I think first-generation students hold a lot of shame, but honestly, reaching out for help is the only way that I could have made it,” New said.

Minh

Unlike New, first-year Minh Vong grew up always knowing that one day he would attend a university, even though his parents never could.

Born in Southern Vietnam, Vong spent the first few years of his life living in a small town, where his parents worked on a farm. Both of them had to drop out of school in the first grade in order to provide for their families. As a result, neither of his parents could read or write. Over time, his father taught himself to read, but his mother remains illiterate to this day. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, having an illiterate parent put Vong at a much higher risk of not only being illiterate himself but also winding up in poverty and ending up on welfare.

“I moved to America at a very young age, and I didn’t realize this until I was older, but my parents made so many sacrifices to get me to where I am,” Vong said.

His parents left their jobs, home and family behind in order to move here. As soon as Vong started attending school in the United States, his parents made it very clear that he was to get good grades, receive scholarships and attend a university in the future.

“They left their whole life in Vietnam, even though they were comfortable where they were,” Vong said. “The reason my parents immigrated was so that I could get an education and wouldn’t have to go through what they did.”

Vong recalls all challenges that he and his family had to overcome when he first moved to Tacoma. In addition to not knowing English and lacking connections to the academic world, Vong had to live in a small house with seven other relatives. His parents had to work multiple jobs at once and the family of eight only owned one car.

“Sometimes we didn’t know if we were going to eat,” Vong said.

As he continued going to public school, Vong began to see that he actually had several things in common with his peers. Among people from a range of backgrounds and different circumstances, Vong found himself a part of a group of friends whose parents also did not attend college.

“The reason I have so much appreciation for education is because I grew up surrounded by people who weren’t educated,” Vong said.

Although this was considered the norm, Vong still felt the many disadvantages of being a first-generation student and immigrant. His parents always set very high academic expectations, but Vong felt that he was often lacking the capacity to do as well as his parents wanted him to.

“It’s hard not having your parents involved in your education. I really had to go through it by myself,” Vong said. “Not only that, but I didn’t grow up in a household where English was spoken, so now my vocabulary is not in the same place as other people’s.”

In terms of grammar and linguistics, Vong’s skills fell short, but that only drove him to do better. He continued to study hard, on top of working a part-time job and playing sports. When it came time to apply for college, Vong relied almost entirely on his instructors at school for guidance, and with their help was able to secure several merit and need-based scholarships.

“Coming to Puget Sound has really motivated me. I am in the same place as so many people that have advantages over me,” Vong said. “I see students who are more privileged than I am and some of them don’t do as well in school as I do, which just goes to show that it doesn’t matter where you come from.”

Above all else, Vong is thankful for his parents’ decision to leave Vietnam 14 years ago. He calls his family his biggest inspiration.

“I want to give back to my parents; I want to give my family a comfortable life,” Vong said. “And when I start my own family, I never want them to go through the things that I went through.”

Andres

Sophomore Andres Chavez grew up believing that the American education system was not made to support students like him. As reported by U.S. News & World Report, students of color were about 15 percent less likely than white students to graduate from a public four-year college in 2013. Perhaps more than others, Chavez has felt the emotional and isolating implications of being a first-generation student of color, but he never let it impede his ambitions.

“The idea of getting a full-ride scholarship to college was implanted on me by my mother when I was in kindergarten, and years later I was able to turn it into a reality,” Chavez said.

Born to underprivileged migrants from Mexico, Chavez was always at the top of his class, even at a very young age. He always succeeded academically and because of this, never seemed to notice any disparity between him and his peers. However, at a certain point in middle school, Chavez realized his parents could no longer help him with his academics.

“I learned to be very independent and work extra hard to achieve goals on my own,” Chavez said.

Like many others, he lacked role models, financial stability and resources on how to pursue college.

“[Puget Sound] was enticing to me because of the full-ride scholarship I acquired; however, I quickly realized that the other recipients had a much different experience than myself,” Chavez said. “I later lost the scholarship after not meeting their expectations.”

After years of dreaming about a full-ride, one of Chavez’s greatest achievements was taken away from him. He felt discouraged and ill-prepared in continuing his academic journey.

“I came into this campus already behind the rest of my peers. I lacked the support systems and quality of resources that many others were privileged enough to have, and because of this, I was stripped of my opportunity,” Chavez said.

After losing the financial support he depended on, he didn’t necessarily expect his struggles with marginalization to continue, but they did.

“The reality is, when you are the first in your family to attend college, it is very easy to find yourself [struggling,]” Chavez said. “There’s a lot of pressure, too, because I’m not just doing this for myself. I’m doing this to show my parents that their sacrifices were not vain, and to show the younger generations within my family and community that higher education is a possibility.”

Chavez has started to feel very alone at this point in his scholarly career, fully impacted by the institutional disadvantages of being a Latino first-generation student. Although he has already overcome many of his own obstacles, Chavez continues to work towards equality and empowerment for other students like himself.

“I see a lot of improvements that could be done in terms of making this [university] a more inclusive space for marginalized people and first-generation students,” Chavez said.

As co-president of Latinos Unidos and a supporter of the former Puget Sound Student Union, Chavez participates in protests and speeches with the hope that all students will have equal opportunities to succeed on this campus someday.

“The most difficult part is the isolation: not being able to relate to others on campus, but also not being able to express yourself at home,” Chavez said. “As much as I love my parents and recognize how much they have done for me, they don’t understand the college experience and the struggles that come with it.”

Feeling out of place in their own home can take a toll on the emotional well-being of many first-generation students and Chavez recognizes this firsthand.

“I often find myself internalizing these emotions and that is something that is hard to deal with,” Chavez said.

Despite all of this, Chavez dedicates a lot of his time to supporting other students who have been in similar situations.

“This educational system was not built for people like us, but there are still opportunities and methods to achieve higher learning. [I want other first-generation students to realize] that college is always an option,” Chavez said.

The Puget Sound Perspective

Although these three students are exceptional examples in their academic achievements, USA Today reported that first generation students across the nation are four times more likely to drop out of college than their peers. These statistics make it clear that first-generation students have a more difficult time navigating the process of higher education. However, this process becomes even more challenging when universities do not provide the proper support for these students and nobody knows this better than Access Programs Coordinator Joseph Colón.

“A campus that is generally made up of affluent white people can be very alienating for some first-generation students,” Colón said. “Our job is to support and supplement the non-material resources that a lot of first-generation students may lack.”

Colón’s work focuses on academic support, emotional support and assistance with college literacy for these students. Having been a first-generation student and being a Puget Sound alumnus himself, Colón has a deep insight on the needs of these students. From his point of view, the University is not meeting them.

“First off, it’s hard for the faculty and staff to build a connection with these students [because] they do not necessarily have the social and cultural competency to support them with high fidelity,” Colón said.

A very small portion of the staff at the University actually comes from a first-generation family, minority background or low socio-economic class and because of this, Colón often felt a large disconnect between himself and the faculty while he was a student here.

“The staff and faculty really made genuine attempts but there was always a bridge between us that needed to be traversed before that relationship was built,” Colón said.

If better relationships existed between the faculty and first-generation students, Colón believes that more Puget Sound students would thrive and less of them would feel the need to transfer. In addition to the separation between the staff and students, Colón has also noticed that students lack the community support they need.

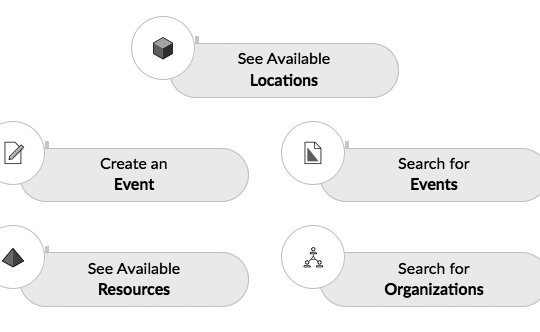

“There is no ‘First Generation Union’ or anything similar and the social and cultural resources that do exist on campus are not as easily accessible as they should be,” Colón said. Colón also believes that the school does not provide enough resources for first-generation students to get involved with jobs and careers during the summer or after school. Furthermore, he feels that this school does not take into account that these students may come from dangerous or unsupportive backgrounds.

“When the holidays come around, many first-generation students don’t have anywhere to go and I think we could extend housing to continue through the holidays and summer,” Colón said.

As coordinator of the Access Program, Colón continues to work on providing grant money, work study, and résumé building opportunities to students from marginalized communities who need them. He also meets with many first-generation students weekly to check in and make sure they are comfortable on this campus.

“A lot of first-generation students are able to do very incredible and dynamic stuff once they get to college, and my job is to support them until they can exceed,” Colón said.