Death & Color: Tacoma Art Museum’s 11th annual Dia de los Muertos festival combines celebration and commemoration

The lobby entrance of the Tacoma Art Museum was bustling with life. Animated children, their faces painted into colorful death masks, chattered and scampered, many of them fixed with fascination by their own additions to the scattered explosion of chalk art that created the day’s sidewalk scenery.

Inside, the enticing smells of churros and burritos filled the busy air. It was the Tacoma Art Museum’s 11th annual Dia De Los Muertos community festival, and if the lively crowd was any indication, the event was a success.

According to a statement made by Amanda Diaz, president of Latinos Unidos, the celebratory nature of this day is in lieu of the belief that “the gates of heaven are opened at midnight on Oct. 31, and the spirits of all deceased children (angelitos) are allowed to reunite with their families for 24 hours,” and the next day signifies adults doing the same.

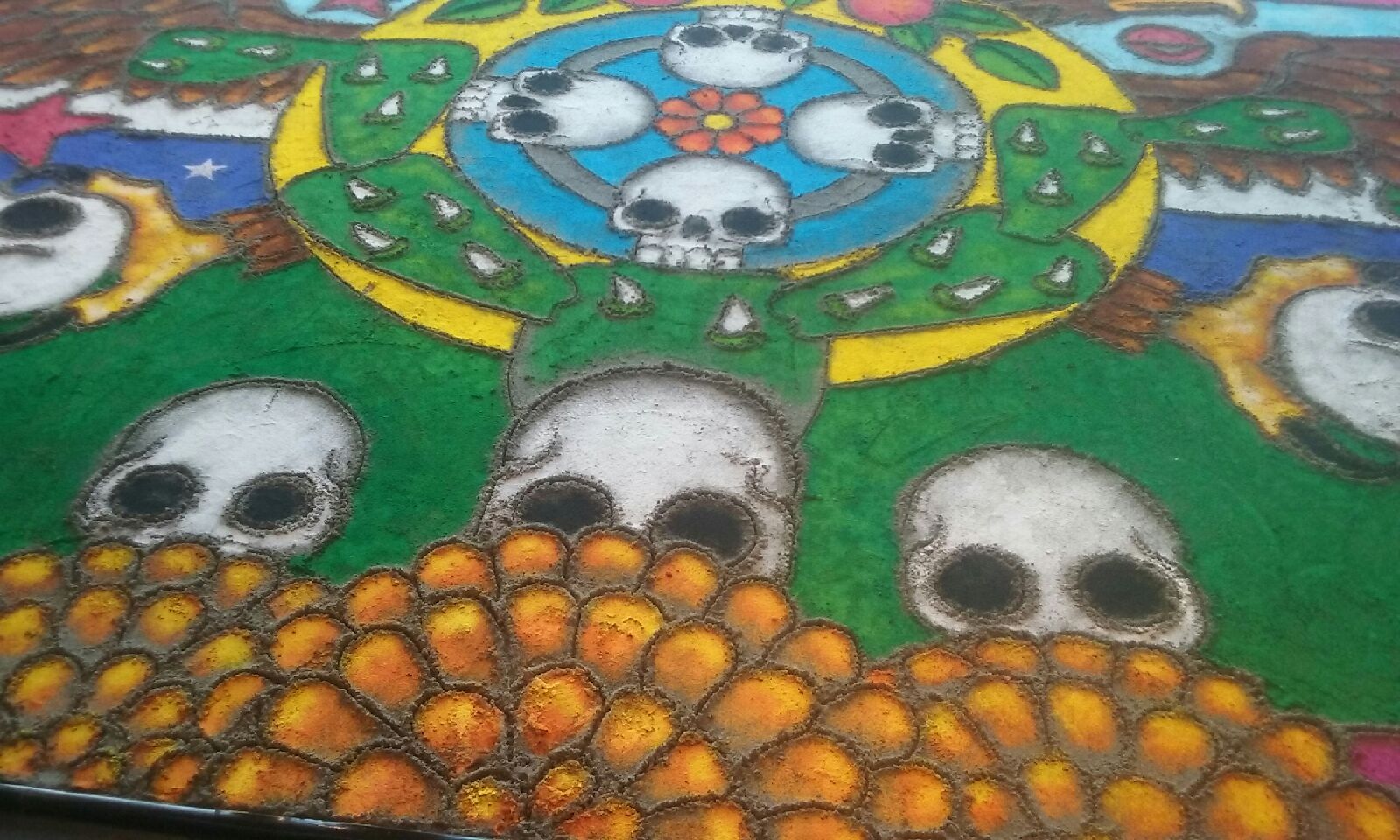

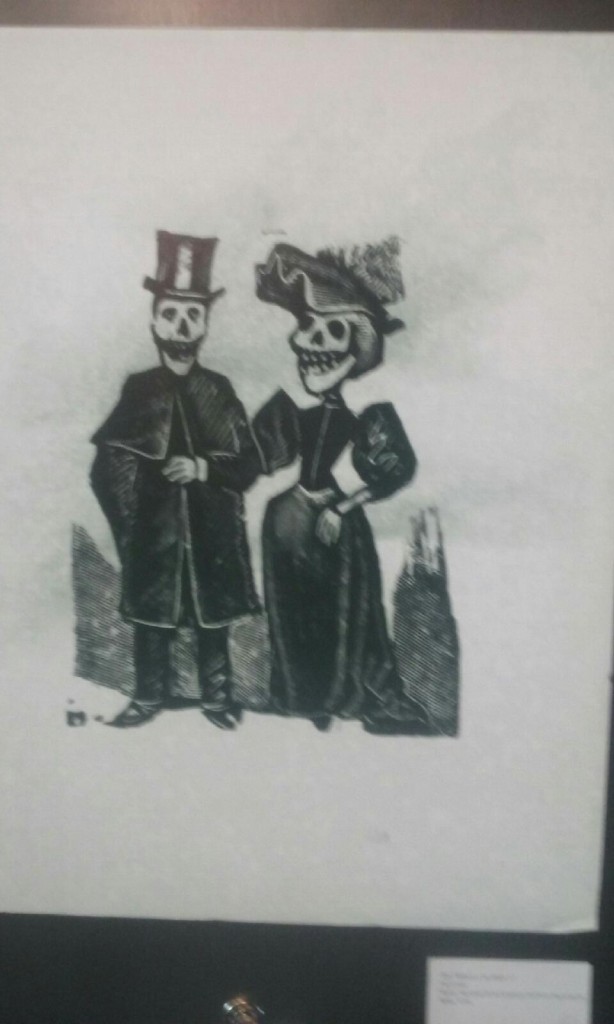

Created by the indigenous people of central and southern Mexico, it is a celebration of the goddess of death Mictecacihuatl and the Catholic holiday All Souls and All Saints Day and creates a chance to celebrate with loved ones spanning down from generation to generation. Here, the collision of life and death came in a burst of color. Walking in, Rene Julio’s colossal sand painting embodied this, with skulls fanning out from what looked almost like a landscape of greenery. Families created bone-filled linocuts amid displays of prints with traditional images of the happy dead. The consequences of the day’s costume contest swam among the crowd, with couples and families alike donning elaborate outfits and skeletal makeup.

After a performance by Mariachi Lucero, the traditional Aztec dance group Danza Quetzalcoatl de Olympia provided a fantastic performance of traditional dances that had been passed down for centuries.

“Every step means something,” Wendy Guzman, drummer for the troupe and daughter of troupe leader Norma Herrera, said, and they haven’t altered a single move from these traditional dances. They tell stories, and one can gather a great sense of the narrative quality of their moves when watching the four-feathered dancers stomp in and out of each other’s proximity to the swelling, dynamic drums, hailing upwards with their hands and emphasizing climactic moments with quick shouts. Everything about their performance was intricate, from the massive, densely decorated headdresses that fanned out several feet, to the tightness and variation of their synchronized movements.

Most of them had made the costumes themselves, with love and care for the dense symbolism painted onto each one. Herrera explained that the pair of blue hummingbirds across the bottom piece of her outfit represented her, how the exact date and time of her birth determined what color and animal was with her throughout the day.

“And for the night, I have the coyote,” she said with a satisfied snarl.

A grin spread across Guzman’s face as she explained how she made her drum herself, shaving off all of the bark and carving it from a single, massive tree trunk.

“We call him Grandpa, and you’ve got to respect Grandpa,” she said.

The main attraction of the day, however, was the overwhelming number of altars spanning multiple floors of the exhibit. All were created by members of the Tacoma community. Each altar provoked a complex feeling that was different than the one provoked by any other, and these distinctions showed just how intimate and personal a collection of objects could be. Photos of dead loved ones amid foods and objects they loved communicated a sort of interaction among the living and the dead. One couldn’t help but think, someone put these there for the dead, someone who knew them so intimately they knew exactly what candy and brand of lipstick to put under their picture frame.

Though nearly all the works felt intensely personal, some were political as well.

A highlight was the cleverly rendered altar for Graffiti artist who had passed, built upon a stepladder and brimming with stylized graffiti art, paint cans and equipment that served not only as a memorial to the artists themselves, but the art that had been callously sprayed over in white and beige.

An especially hard-hitting work was dedicated to trans women of color who have died in the past year, their young faces smiling among bead and lace.

A massive altar dedicated to the children who died in Gaza steeped the atmosphere in a weight so heavy one could feel the crushing in their chest just as they passed.

Regardless of scale, all commemorations of the dead, or invitations to let them back in, were valid that day. A bony community altar commemorating dead pets stood not too far from an altar commemorating the death of Latin Culture itself. One work, fittingly, had a cheeky, suited paper-maché skeleton holding up a piece commenting on the appropriation of Dia De Los Muertos. Our own Latinos Unidos club on campus usually has an exhibition during this festival, but this year found it more important to make their voices heard on campus with their Death of Diversity altar set up in the Student Center.

“The Death of Diversity is a Political Statement,” Diaz said. “We as students from marginalized backgrounds feel like we are both living and dead because we are ignored, invisible and seemingly unimportant to our campus community.”

The altar gave acknowledgement to several marginalized groups and significant figures in Latin culture.

“Day of the Dead is becoming very popular in the U.S.— perhaps because we don’t have a way to celebrate and honor our dead,” Diaz said.

The mixed display of solemnity and joy at the Art Museum’s festival showed a glimpse of just how fulfilling and cathartic such a celebration can be. Participate with love and respect, and it can help carry one through the chilly winter months as they find harmony within the deaths and lives they are a part of.