If there’s one thing artist Humaira Abid is bad at, it’s being silent. Whether it be in her life, subject, or chosen medium, Abid does not conform to anyone’s expectations. Her work is strikingly beautiful, but she does not leave out the blood, sweat or pain.

Abid, an award-winning, nationally- and internationally-acclaimed sculptor and painter, was on the University of Puget Sound campus from Oct. 22–26 as part of a short-term teaching residence at Puget Sound called “Living Art.”

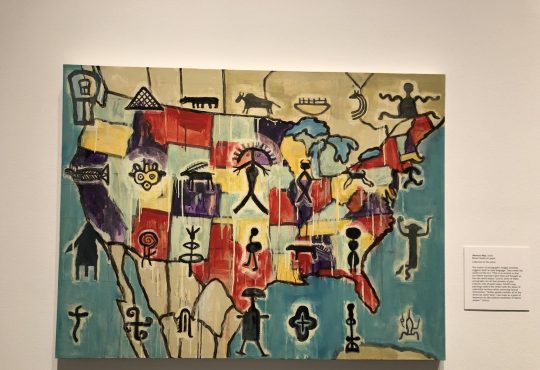

Abid is an immigrant from Pakistan, a Washington resident and an instructor at Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. During her stay she shared her latest series, “Searching for Home,” with the Puget Sound community.

“Searching for Home” captures the often-violent experiences of refugees through intricate wood carvings and vibrant miniature paintings. Abid focuses on the struggles of women and girls in the refugee crisis and refuses to be quiet about subjects considered taboo, such as rape and menstruation.

Abid’s wooden carved pieces would be indiscernible from real objects if it weren’t for the tree rings on their surface. Her miniature paintings are equally well-crafted. However, the beauty of Abid’s work is not merely for the viewer’s consumption.

“I think art has this advantage that it can bring people closer by seducing them through the beauty of the work and then open up all these layers of meaning behind them and then make it easier on them to discuss,” Abid said in an interview with The Trail. This is the purpose of Abid’s work: to open up discussions about subjects deemed unmentionable.

Abid is used to hearing about the struggles of immigrants and refugees in Pakistan. Her own parents migrated from India during Partition, when British India was divided into two independent countries, India and Pakistan. The Partition resulted in displacement, violence and a large-scale refugee crisis. When she moved to the U.S. in 2008, her connection with the concept of home and belonging deepened even further.

“I moved here and then I became an immigrant — although out of choice — but still there were some similarities that I felt,” Abid said.

She was interested in stories of migration, particularly from the perspective of women and girls. It troubled her that most refugees’ stories were only told by men and that women’s issues were merely brushed aside.

“I often ask this question: what if woman had menstrual cycle at the time and was moving? What did she do to get by that time if she was pregnant, breastfeeding? So all of these issues that nobody is really investigating,” Abid said.

In one piece, “Borders and Boundaries,” which was featured in her presentation in Rausch Auditorium on Thursday night, a pair of underwear hangs delicately from a barbed-wire fence with a thick red blood stain. Both the barbed wire and the underwear were carved out of wood but give the impression of sharp metal and soft fabric. If you peered through the fence you could see another piece, “Fragments of Home Left Behind.” This piece depicts a wall riddled with bullet holes and lined with five miniature portraits of young refugee girls and women, many of whom have bruises or broken bones. These works are painful, but they shamelessly give a voice to the refugee women and girls suffering from violence and lack of basic necessities such as feminine hygiene products.

Abid’s earlier works were much more personal. Growing up in Pakistan it wasn’t easy to be open. Issues like sex, menstruation, puberty and fertility were considered taboo and weren’t discussed. Abid used her childhood as well as her experience with miscarriages in her work, and found that by sharing her story she was opening doors for others to share theirs.

“There were other women who came to the show and started crying and started opening up — started sharing their stories,” Abid said.

When asked about the importance of normalizing these so-called taboos, Abid answered quickly that “It’s the most important thing. … Growing up we were discouraged from openly discussing these issues and nothing changed so I think not talking is not resolving it.”

Abid’s time on campus showed that openness elicits change. The impact of Abid’s work was easy to see by the numerous questions asked at the talk. Her work created a dialogue about social issues that many may have not even considered before. Her passion was infectious and proved that the individual has the power to ignite change.