New perspectives on modern demonstrations; A call for a deeper understanding of the innovative demonstrations arising

All across the country, marginalized groups have been called to action. In a surge of social upheaval, the past few years have seen a massive resurgence of public protests, social media spreads and a general rise in the public eye of people that have otherwise been overshadowed by normative culture.

For example, the Occupy Wall Street movement protested socioeconomic disparity in the United States. Hundreds of individuals took part in massive stands against the billionaire elite. More recently, movements such as Black Lives Matter have stood up to the institutionalized racism that has led to the end of innocent black lives, many at the hands of law enforcement.

It’s no question that the rise in protests has been spurred on by a wave of brave people who speak against the status quo. But the methods of protest vary, from articles in media publications to conferences and discussions in academic settings to public demonstrations.

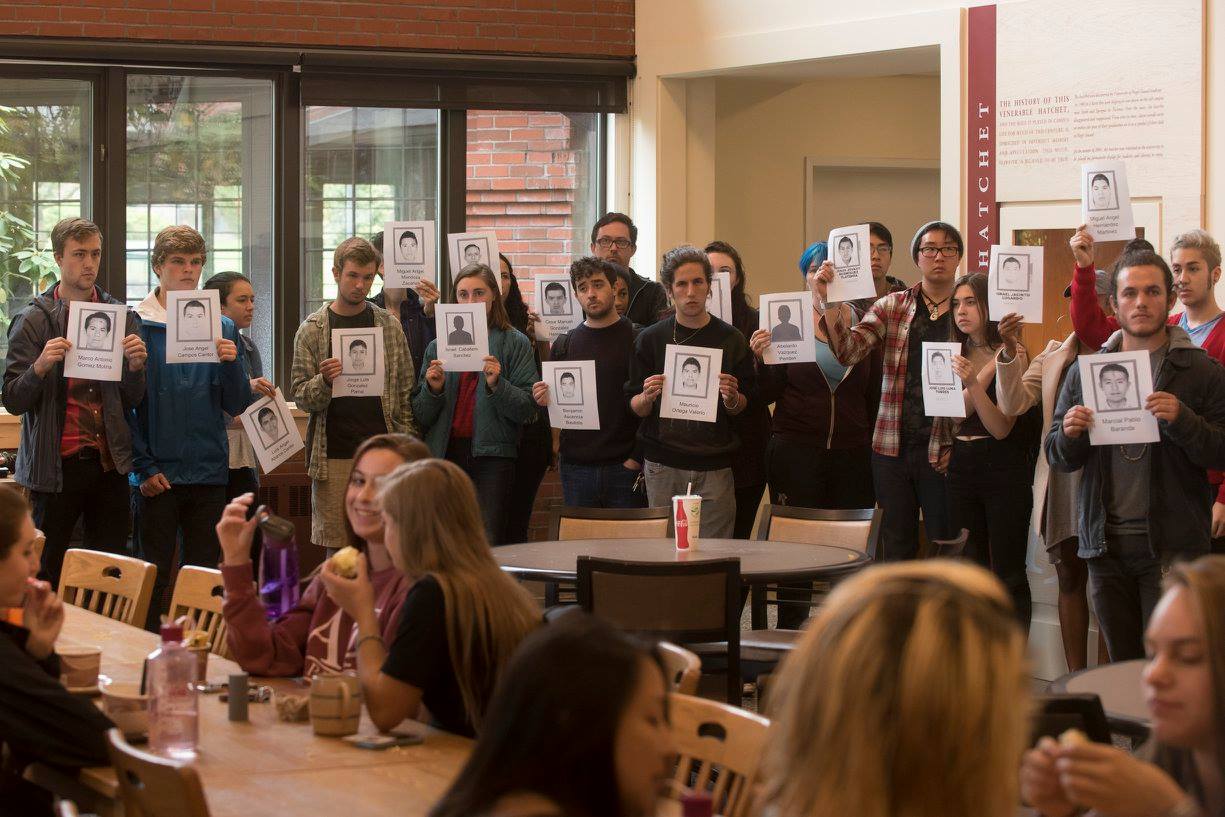

One such method of public demonstration is the disruptive protest. A disruptive protest is exactly what it sounds like. An event or occurrence, most often in a public venue, is interrupted by one or more protesters who express their stance on whatever issue they represent. Here at Puget Sound, the Black Student Union created a disruptive protest last semester with a Die-In, where protestors laid on the ground in the S.U.B. to represent black bodies that had died at the hands of a racist system.

Was it successful? That’s an unfair question. There is no real “success” in a protest, because as most protestors are aware, changing a system requires more impetus than simple acknowledgement. Such awareness can start the gears turning in order to create something beyond a demonstration. The eventual hope, however, is that protesting will create change in the status quo.

But they don’t always create a positive outcome. One of the more recent examples of a controversial disruption was in Seattle, where Senator Bernie Sanders was speaking and members of Black Lives Matter took to the stage. What followed was considered by many to be disruptive, even rude, claiming that interrupting a candidate like Sanders only hurt the movement by giving fuel to the fire of criticism.

At first, this may be a common reaction. After all, what benefit would come from interrupting a speech like this? What positive impact would this have on the public opinion of Black Lives Matter? It felt like a compromise of integrity, where allies were being cast aside for the sake of fulfilling a personal agenda.

Reading further, however, there is more to this protest, and more to the challenge that these individuals were giving to Sanders and to the incredulous population focused on politics and race in this era of massive social discourse.

The first line that came to mind was the truism of “don’t fight fire with fire,” or alternatively, “don’t fight hate with hate.” It’s a chorus that comes up again and again in criticisms of radical or passionate protests, and the problems that come with it reflect both the critics and the criticized. The most important reality is that the people who already express hatred and violence towards movements like Black Lives Matter have not and will most likely not respond to objectively peaceful approaches from the people that they currently hate. In the face of such intensity, “peaceful protests” accomplish no more than passivity does.

However, the expressions of the few, if pronounced loudly enough, will be taken as the reflection of the many. Especially online or in heavily trafficked media outlets, the use of inflammatory language reflects not just on the individual, but on every member of the group to which the individual belongs, majority or minority.

In the case of the Seattle protestors, it’s easy to see how someone might wrongfully view them as being unable to see the forest for the trees, and see Black Lives Matter members as nagging for attention by disrupting the “only candidate that wants to help.” It’s a misunderstanding, of course, but the reality is that people will judge the many on the actions of the few, and the common individual will be treated as the radical outlier.

Most importantly, acts of disruptive protests are not violent. They are not acts designed to beat down and diminish, but rather, acts of passion and of challenge. The challenge they bring up is the challenge to question the status quo, and to force the layman to accept the truth that lies beyond what they have been led to believe.

What do the Puget Sound Die-In and the Seattle protest have in common? Both of them took the preconceived environment of normalcy and erased them to show the reality beyond the so-called normative. How did Puget Sound students respond to navigating a maze of bodies, of black lives lost too soon? How did the presidential poster child for equality respond to having his podium seized by the once-voiceless?

From the surface, yes, it was rude to take over the microphone of a speaker who people had expected to speak, and who might be rightfully irked that this opportunity was taken. Beneath the initial emotional reaction, though, there’s the question asked of white supporters, of the normative public: what is a protest if not a push against the notion of propriety? Why should a group of protestors have to adjust their agenda to support the timetables of people who would not be listening if their lives had not been interrupted?

Disruptive protests are not a popularity contest. Rallying supporters does not mean asking for people when they are most available, or when they can easily jump in to the fray. It asks the public to stand when they have been seated, and to march when they have been walking. It asks the individual to question their support, and whether or not they are truly doing all they can do to help those with whom they claim to stand.

It is natural to feel discomfort for this reason.

The person that you think you are has to deviate from the beaten path. Many people are unable to do this, because of energy, courage, time, stress, or other obligations.

But what matters is the appreciation of those who are able to deviate, and that at one point, they felt the same tear between the comfort of the self and the lives of the other.