By Andrew Benoit, contributing editor

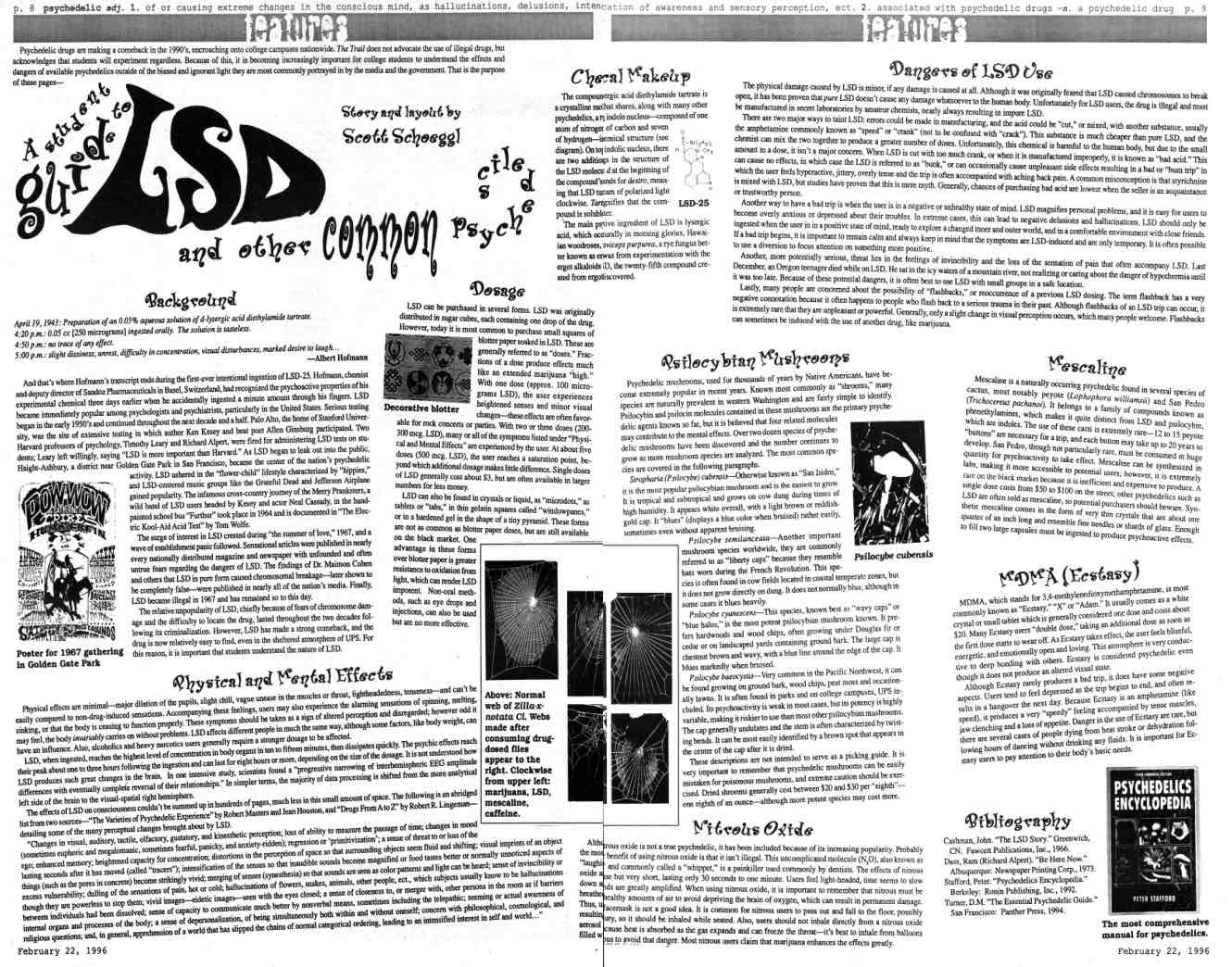

In February of 1996, The Trail published a two-page spread detailing the effects of a variety of psychedelic drugs, including their background, uses, and dangers. They explained their reasoning for publishing an article on illegal substances. “It is becoming increasingly important for college students to understand the effects and dangers of available psychedelics outside of the biased and ignorant light they are most commonly portrayed in by the media and the government.”

In the 26 years since Scott Schoeggl outlined the pharmacological makeup and effects of psychedelics for Trail readers, much has changed in the world of psychedelics, both on campus and in academic circles. Today, psychedelics blur the lines between recreation and therapy, commodity and subversive tool, and science and humanities. Put simply, unraveling the use and view of psychedelics on campus, is, well, trippy.

Given the fact that LSD usage increased by 54% between 2015 and 2018 alone among Americans according to The Scientific American, it should come as no surprise that it took little digging to unearth psychedelic participants beneath the University’s shiny surface. Due to the illicit nature of this article, all students are referenced by pseudonyms. One student, Jay, said that Shrooms, LSD, MDMA, and DMT are all common on campus. “Pretty much you name it, at least in certain circles. People are definitely using the full gamut,” they said.

It’s not hard to see why psychedelic drugs are popular on campus. Students describe feeling more connected with themselves, a stronger sense of self compassion, and a break from the drudgery and unpleasantness of life. “My usual state of being is boring. I totally use psychedelics as a way to get out of my own brain and try to experience the world for what I believe it really is,” said Sandra, a senior who is taking two classes related to psychedelics on campus.

Besides their personal benefits, nearly everyone who talks about psychedelics mentions their ability to connect people together. Professor George Erving, who teaches one of two classes on campus related to psychedelics, explained that a sense of communion with others is present in thousands and thousands of trip reports, and describes how the psychedelic literature portrays the experience. “In our normal mindset, we live within the silos of our own subjectivity and attempt to reach out across space, so to speak, to other silos. But the psychedelic experience instead situates the self in a kind of forcefield of betweenness with others, where you, in some sense, are the other,” he said.

Students also reported having these kinds of experiences for themselves Sylvia mentioned that she took psychedelics in Amsterdam when she studied there and became very close with people who she had previously felt separated from. Sandra described how connected she felt to members of her family who had struggled with drug addiction, and how much more empathy there was between her and her family.

Sylvia, like many on campus, doesn’t necessarily take psychedelics for a mystical or spiritual experience, although they do recognize that the spiritual experience is an intrinsic part of the drug. “People who are heavy users, regardless of whether or not they’ve taken an academic course on psychedelics, there is sort of inherent like spirituality aspect of them,” Sylvia said.

Sandra, who said she has been tripping since high school, said that taking a class on psychedelics here on campus dramatically changed her psychedelic experiences. “I had good times but never had like, I don’t know, religious experiences or anything crazy that my brain couldn’t comprehend. And then, actually, since I’ve taken this class, I’ve had multiple trips where I have like, felt like I didn’t like understand reality.”

Not only do psychedelics blur the line between recreational and spiritual experiences, but they are also heavily beneficial in therapeutic contexts. Professor Erving explained that ever since psychedelic research started to pick up steam again after its decades-long prohibition, it has become increasingly clear how potent the therapeutic power of psychedelics is. According to him, one or two guided psychedelic therapy sessions can have a 50 to 80% success rate even a year out from the treatment and are often effective almost immediately. To put that into perspective, according to Scientific American, SSRIs – the main way depression is treated today – need to be taken every day in perpetuity, take weeks to work, and see lower mitigation of symptoms than psychedelic therapy. Professor Erving emphasized just how impressive the research shows psychedelic therapy is. “They are so ridiculously far beyond anything else that’s out there. It’s really quite stunning.” Therapy doesn’t just have to take place in a clinical setting. Students also see the therapeutic benefits in their own use. Jay acknowledges the dual role that psychedelics play on campus. “People that I know use them both as recreation, and medicinally I guess, or as self-medication,” they said.

Students also noted the non-addictive nature of psychedelics, their general accessibility, and their experience compared to other popular drugs on campus. “I think it’s, by nature, less addictive, closer to the earth, and has more consistently positive effects. People have anxiety attacks on weed and they take cocaine and they feel like they are taking Adderall or they take it and they forget five hours of their night,” said Sylvia, a senior.

While Professor Erving understands that continuing to prohibit the use of drugs outside of clinical settings is impossible, and maybe not even desirable, he warns that taking the drugs should not be done lightly. He explains how weighty the psychedelic experience can be, according to the wealth of scientific literature surrounding it. “These drugs are work. They take you deep into yourself and they can provoke the most profound questions about ‘who am I’ and ‘what is the nature of this thing we call reality’. If you’re not ready for that, you’re in for a rough ride,” he said.

These deep questions that the drugs raise are part of the reason for the class that Professor Erving teaches. The way he sees it, the psychedelic renaissance is upon us and there is no point in not learning what we can from them. His class – one of the few courses across the country dedicated to the psychedelic renaissance – deals with everything from art, to metaphysics to neuroscience. Professor Erving sees great merit in what he and his students are studying. “It’s not a Frou Frou, sensationalistic side topic. It’s a really legitimate topic that is really well-suited for liberal arts education,” he said.

The wider psychedelic renaissance in academia, which gained popularity in the mainstream partly due to Michael Pollan and his book “How to Change Your Mind,” is just as complex as the use of them is on campus. Neşe Devenot, a postdoc at the University of Cincinnati who studies psychedelics through the humanities disciplines, sees troubling issues in the field. She explained that the landscape has shifted due to the immense amount of money to be made in psychedelics. “Some of the people involved in the field right now are interested in their own money and power and not as interested in what’s necessarily best for people in general,” they said. Devenot explained that pharmaceutical companies are trying to make as much money as possible by patenting everything they can get their hands on related to psychedelics, even things that they didn’t invent. “They’re trying to make as much money as possible, but you’re dealing with substances that have long histories of cultural use,” she said.

On the other side of the psychedelic coin, Devenot describes their issues with what they call “true believers”; people who are so committed to the cause of psychedelics that they start to play fast and loose with science. “Some people in the field genuinely feel like psychedelics are waiting to save humanity, and so we need to just move as quickly as we can and just scale this up for as many people as possible, and that can be a quite dangerous approach when you have this ‘ends justify the means’ mentality,” she said.

Students are aware of a lot of the discourses that surround psychedelics today, and several called out big pharma. Jay mentioned that, despite still loving psychedelics, they are less gung-ho about everything associated with them. “I used to think that anything pro psychedelics was dope, but it is worth thinking about more critically,” they said. To Devenot, part of the real power of psychedelics lies in their disruptive and regenerative abilities. She explains that part of the reason deeply unequal systems are so powerful is because they present themselves as the only way to live. “There’s something about the way that hegemonic norms and ideologies become like the water that a fish swims in – like it’s so pervasive that it can’t even be seen,” she said. According to her, psychedelics allow people to pause and cause them to see things differently. “There is that latent potential of getting people to envision other forms of social relating that are not extractive and exploitative. That can be an inspiration towards changing material circumstances and building a better world that serves all of us instead of the few at the top,” she said.

Many students echoed Devenot’s sentiments. Sylvia mentioned how the things that are important in society just aren’t important when you’re tripping. “The revelations and feelings you get on psychedelics are not compatible with the way our society is set up. We’re very productivity-driven, independence-valuing, capitalistic robots and on psychedelics, you devalue those things,” she said.

However, everyone was careful to emphasize that psychedelics aren’t a magic bullet for solving anything. Taking shrooms won’t stop capitalism from exploiting you. Nor will it automatically fix your depression. It won’t even make you a cool person. Both Professor Erving and Devenot, despite their firm belief in the great potential of psychedelics, cautioned students. Psychedelics can be dangerous and are still highly illegal. While some students were excited at the prospect of encouraging other people to take them, Sandra had some reservations. She feels like once people find out how easy they are to access, there is an immediate escalation to taking them. “I just feel like people just need like a better education on them before they try them,” she said. An education on something that promises to so profoundly transform our ways of thinking and our culture sounds helpful, even if you never plan on tripping yourself.

There is almost no question that psychedelics are here to stay. With academic, pharmaceutical and financial interests now deeply invested in the drugs, it seems to be only a matter of time before psychedelics become totally mainstream. Whether that happens in the hands of big pharma or in a way that destabilizes exploitative and unjust systems operating today is still unclear. Either way, students across campus are learning about and taking psychedelics. Whether it’s spiritual, recreational or therapeutic, University of Puget Sound students are “turning on” and “tuning in” to the psychedelic renaissance. Whether “they drop out”, as Timothy Leary suggested in the late 60s, remains to be seen.