By Milo Hensley

The Trail is excited to introduce our readers to the new Archives section: a column that dives into historical analysis with the purpose of grounding our understanding of The University in the analysis of past publications. All history carries the assumptions and biases of those who create it, and productive historical study acknowledges its connection to the present. This feature will republish historical material, attempt to learn from those who came before us, and ground our understanding of The University today in its history. Happy diving! Chloe Shankland: Archives Editor

Our plunge into the Archives of The Trail begins with an April 10, 1970, edition, which focuses the entire newspaper around a single topic: “The Revolution”. Upon first encountering this piece, the gravity of the language used, and its relevance to our world today was striking. Insightfully, the editorial introduction (attributed to no writer in particular) states, “If the world around us seems tranquil and progressive it is only because we exist in an environment of contrived passivity.” Studying the history of revolution allows us to deconstruct our contrived passivity. There is no moving forward in ignorance. The article highlights many different facets of revolution in the United States at the time. These include everything from Women’s Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and the Chicago Conspiracy Eight, to orgasm, rock music, and drugs. The newspaper also contains tangible measures, including information about a draft protest, a guide on conducting urban guerilla warfare, and a list of dates and locations tracking attacks on police officers.

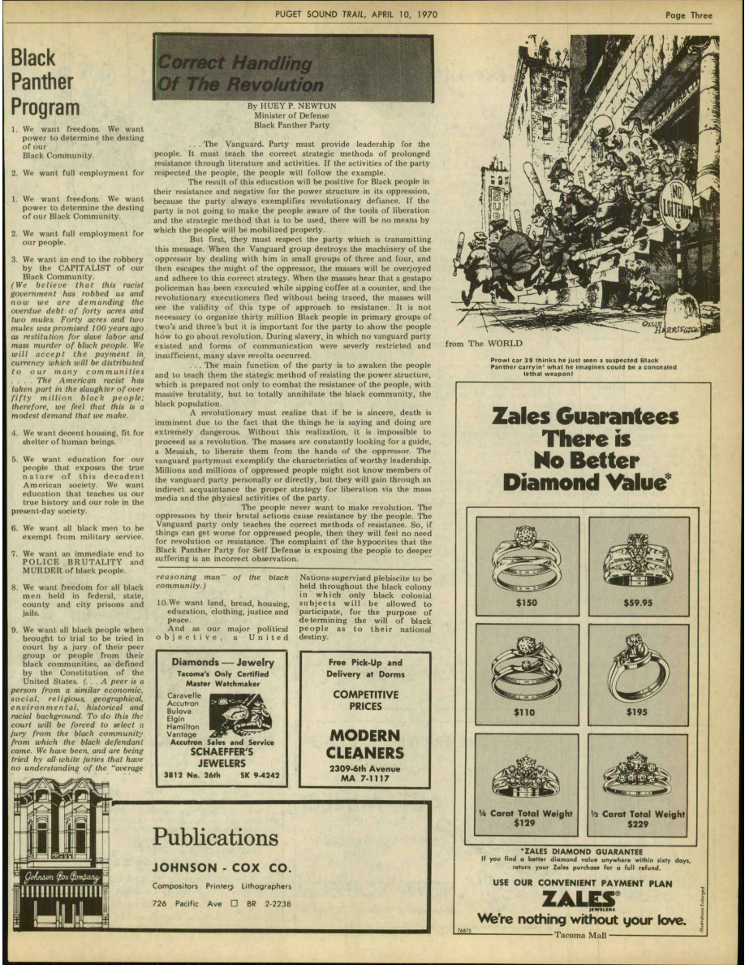

In honor of Black History Month, page three of the document has been selected for republication. The page highlights the Black Panther Party with a satirical comic about police violence. As well as reprinting a copy of the “Black Panther Program,” and part of a speech called “The Correct Handling of the Revolution” by Huey P. Newton, a party founder.

The publication of this archival issue comes shortly after the first Black History Month in this country. The celebration of Black history and culture existed long before Black History Month was recognized as a national holiday. According to the New York Times, February as a period of observance and education was first proposed by Black students and educators at Kent State in 1969, celebrated for the entirety of the month for the first time the following year.

It is essential that we understand the history of the Civil Rights Movement in order to contextualize the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement; to remind us that the contributions of Black people are integral to the development of this country and that the ongoing fight for a level playing field is hard-fought. We must also take note of how contemporary demands echo those of the past. This is explicitly clear in our dives into the archives. Our systems of policing, trial and imprisonment are still racist. True history is still not taught all over the country. The Panthers’ demands for housing, employment, food, clothing, land, justice and peace go unmet to this day.

Revisiting this edition of The Trail from a contemporary perspective, it is pleasantly surprising that the student journalists of 1970 were taking a stand by showing their support for Black liberation. It also raises many questions about the role of journalism at a university like ours and how to move forward from here. If The Trail staff in 1970 were willing to risk coming across as biased in order to give explicit support to the social movements of their time, why shouldn’t we do the same now?

As The Trail restarts, it is up to student journalists to publish radical stories. The status quo thrives on neutrality in times of injustice. Climate denial, xenophobia, the right-wing effort to censor critical race theory in schools, and a whole host of other harmful viewpoints are legitimized by mass media every day for the sake of appearing unbiased. These issues would be central to a 2022 “Revolution” publication. The words of the anonymous author of the 1970 edition continue to ring true, “As we become aware of the turmoil each of us will be forced to examine our personal values, assumptions and beliefs.”

The nature of white supremacy in the United States has changed somewhat since 1970 but is still a formidable force in our culture at large and in our university. At some point, student journalists need to make a decision on whether to use their power in a way that supports movements for justice, or to remain complacent in the systems of oppression we claim to oppose. Reading and studying voices from the past is one place to start. We should publish material from radical grassroots organizations. We should encourage civil disobedience and student protest. We should deconstruct our contrived passivity and confront our apathy. We can learn from the horrific ways in which The University has upheld white supremacy since its founding, and simultaneously take inspiration from those past generations of students who were brave enough to raise their voices against it.