Every object has a story. But have you ever considered reading a story to an object? This is the central experiment of Sarah Bodman’s book arts project, “Read to Me,” wherein the London-based artist collaborated with a psychometric reader in the Netherlands to find the hidden stories behind a collection of objects purchased at second-hand shops across Europe.

Psychometry — a word that derives from the Greek roots psukhē, meaning “spirit” or “soul,” and metron, meaning “measure” — is just that: measuring the soul or essence of objects. Also known as “token-object reading,” it is a form of extrasensory perception characterized by the ability to reveal the previously unknown history through physical touch.

According to her artist statement, Bodman first became interested in psychic readings during her month-long residency at the Visual Studies Workshop (VSW) in Rochester, New York. It was there that she first read about the infamous Fox Sisters, three sisters who gained rapid acclaim in the 19th century in Rochester as spiritual mediums.

“As I sat at the table reading in the archive at VSW,” Bodman said, “I imagined that the Fox Sisters would have been at a similar table in a similar large mansion house over 150 years ago, thrilling their audiences with ‘spiritual encounters.’”

As a means of combining her artistic passion with her love for reading novels and poetry, Bodman decided to find a psychic reader of her very own in order to find a way to communicate ideas or messages from books to material objects.

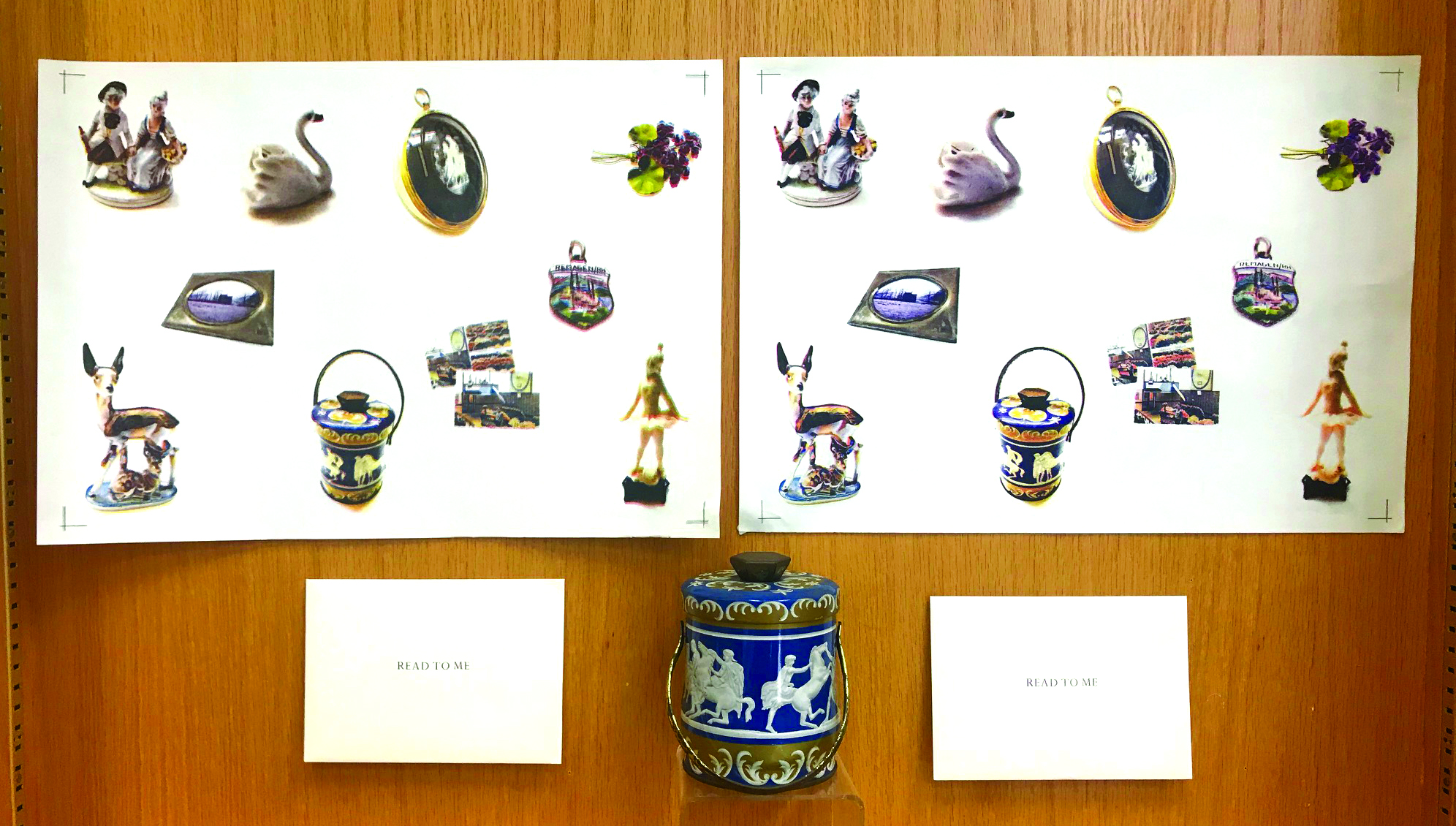

Bodman purchased 10 different objects from second-hand stores around the U.K. and Europe and read each of them a story, poem or chapter from her favorite novel. Afterwards, she shipped the objects to a psychometric reader to hear what the objects could “read” back to her.

The final product is a series of four-color risograph print books. On each page is a photograph of the object on the right and the object’s history, according to the psychic reader. What results is a quaint, yet haunting, meditation on the impressions we leave behind in the material world.

“What I really appreciate about Sarah’s work is her ingenuity,” Library Director Jane Carlin said. Carlin developed a professional relationship with the artist many years ago, while traveling in London.

“She takes on new thoughts and ideas and she is always looking at new techniques and new technologies, like new printing methods and laser cutting. But she’s also very innovative. Who would have thought to use psychometric readers?” Carlin said.

Bodman’s project certainly goes outside the box. In fact, it goes outside this entire earthly plain! The object-stories included in the booklets are brief yet poignant, providing readers with just the faintest image of the object’s past life, like a snapshot from a dream.

One story of vintage cameo reads: “It was made with precision. The person who received it was a woman. She lived in a tight regime where she had to survive. She died young. She was attached to this cameo. … It also has to do with lost love.”

These haunting descriptions, combined with the images, which all possess a certain ethereal glow thanks to Bodman’s risograph printing technique, come together to create a truly evocative collection.

Whether you believe in the validity of psychometry or not, Bodman’s exhibit makes us reconsider the banality of everyday objects and ask ourselves what hidden stories they might harbor. You can check out the exhibit for yourself in Collins Memorial Library until May 12.