Let’s begin with an experiment. Take a moment to notice your breathing. Notice the way the skin beneath your nostrils stretches as you inhale, the way your chest gently rises and falls, the movement of air inside your lungs. Now, as you go on to read this article, try and keep noticing. Let’s see how long you can maintain this heightened awareness.

This was the same challenge Religion Professor Stewart Smithers posed to the audience during his portion of a joint lecture with Puget Sound alumna and artist, Maria Jost. On Thursday, November 29, at 6:30 p.m., the Puget Sound Arts and Sciences Salon Series brought Jost and Smithers together to discuss neuroscience, brain-care, mediation and what it means to be human.

Smithers’s experiment was inspired by the Hesychius tradition of eastern orthodox Christianity, a tradition that centers around learning to pray without ceasing. According to Smithers, Hesychius prayer is mostly “formal and ritualized.” It consists of repeated inner gestures and must consciously include “your mind, your feelings, and your body at once.”

“This idea of course, is pretty much impossible … but they try. … Even in their failures, they manage to establish a certain measure of their capacity for continuous attention,” Smithers said.

And so, rather than attempt the impossible task of praying ceaselessly, Smithers urged the audience to simply try and apply that same “continuous attention” to their own breathing until he finished speaking.

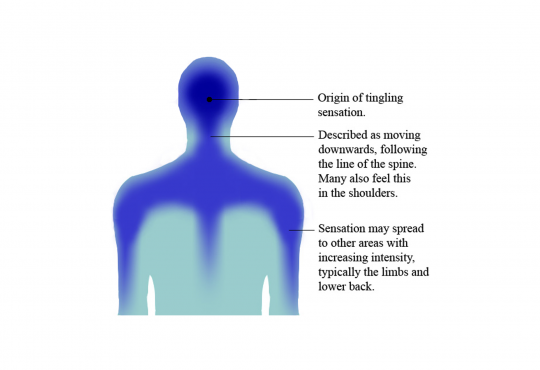

Research now shows that activities, such as prayer, meditation or simple “mindfulness practices” for the less religiously inclined, actually physically affect the structure of the brain.

Jost spoke to this in her portion of the lecture, as she explained: “Neural circuits can either be reinforced or pruned, so the circuits, or connections that you use a lot, are reinforced, and the ones that you don’t use are pruned away.”

This can work both to our benefit, as in the case of learning, or to our detriment, as repeated negative thought patterns can become codified in our brain’s neural circuitry, trapping us in what Jost described as a “negative ruminative cycle.”

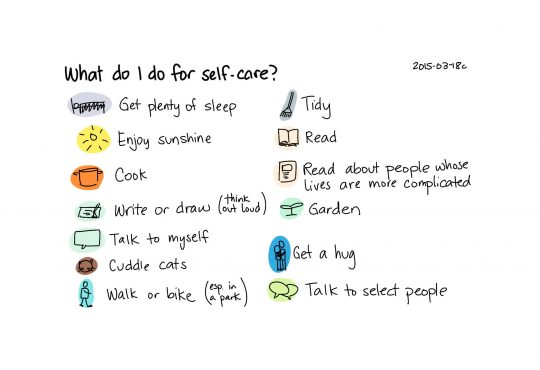

The key to maintaining a healthy brain, according to Jost, is to practice mental exercises that reinforce positive neural networks instead of negative ones. While these exercises of course aren’t the same as comprehensive mental health treatment, Jost insisted on the importance of taking preventive measures to ensure mental health:

“If a patient were in cardiac arrest, a doctor would not prescribe jogging in that moment,” Jost said. “But at the same time, if somebody hadn’t had a heart attack, we wouldn’t tell them that they don’t need to do any jogging. And I think that we don’t think about our brains in that way enough. It’s tissue and cells and there are things we can do to take care of it.”

It was this lack that inspired Jost’s most recent artistic project. Jost sought to create an art piece that could also serve as a physical resource for preventive brain care practices. What resulted was a piece she entitled “Brain Amulet,” a combination of watercolor and collage art, meant to encapsulate “the atomic interconnectedness of all beings within a single image.”

The original 24” x 24” illustration was then shrunken down to a 3” x 3” card, on the back of which were printed three brain-care practices including practicing 30 seconds of gratitude, 10 deliberate and focused breaths, and physical connection with another organism. All of these practices are scientifically proven to bring the brain out of the negative ruminative cycle.

In our fast-paced modern world, stress is often regarded as the norm. Smithers spoke to this problem towards the end of the evening, describing the ways in which we tend to ignore our mental needs, as we assume mental suffering is just what it means to be alive right now.

“We lose this sort of scale and dimensionality of what health could be, what people could be,” Smithers said. “The world never feels fallen, because we become accustomed to the fall.”

And therein lies the first step in changing the culture surrounding mental health. We must first acknowledge that there is a problem. We must refuse to accept suffering as standard or necessary. We must stop and ask, Am I still breathing?