By Daniel Wolfert

It was as she gathered her notes and clippings for her Feb. 9 lecture at the University of Puget Sound that Susan Stryker – transgender woman, Ph.D. and associate professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona – received an unexpected email from Michael Howerton, editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Examiner.

Howerton’s email was a request for Stryker’s input on the question of gender neutral pronouns, an issue facing many newspapers and other public interest publications today. Torn between the use of the colloquial but grammatically misleading singular “they” and the use of unconventional conventions for gender neutral pronouns, such as “ze” or “ve,” Howerton’s dilemma illuminated one of the many ways in which the increased visibility of transgender issues has disrupted the fabric of our current conventions.

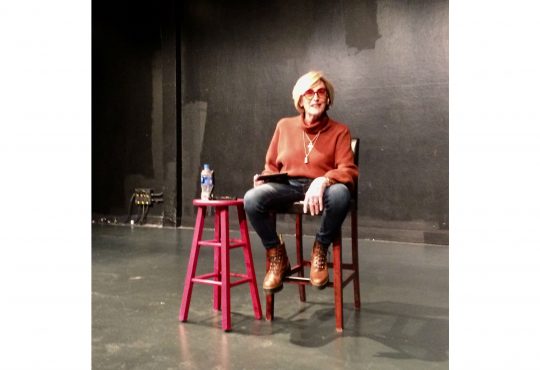

“We are struggling in the present, as a culture, to adapt our very language, our very concepts of personhood, to an emerging material reality in which gender is coming to mean something other than what it has meant in the past,” said Stryker during her swift and whirlwind evening lecture on the current state of the field of transgender studies. She spoke of the issues Howerton’s email revealed to an audience in the University’s Tahoma Room, which was so crowded that half of the seventy audience members were forced to stand or sit by the walls.

This audience was comprised of an enormously diverse array of University students, faculty, staff and Tacoma residents, and several of whom were themselves transgender. Yet Stryker was insistent that the subject of transgender issues, although seemingly remote, is part of a broader relationship between societies and human bodies.

“What’s important to recognize here is that in dealing in what we now call intersex trans and queer issues lies the root of the currently dominant way of conceptualizing and categorizing varieties of embodiment, identity and desire for everybody,” said Stryker. “The social-scientific concept of gender at its root came into existence to explain, and to explain away, people like me, and to smooth over the irritation that our very existence can illicit in others.”

The proposed notion that gender is meant to mollify the disruption caused by people that act in ways unlike the behaviors associated with their biological reproductive organs (i.e. people born with male genitalia acting in traditionally feminine ways and visa versa) is not meant to be taken lightly. Stryker informed the audience in no uncertain terms that the expectation for certain bodies to be associated with certain behaviors – such as the western expectation for biological women to desire children – is just one tool for societies to organize disruptive individuals.

“The other important thing to recognize here is that the entire project of dividing bodies into sexes and moving bodies into genders is an inherently political project – or more specifically, a bio-political project,” said Stryker. Comparable to social hierarchy based on skin color, facial features or body weight, the value placed in those whose sex (i.e. reproductive organs) match society’s expectations of their gender (i.e. conceptions of self-identity and expected behaviors) is a tool to sweep those for whom sex and gender don’t match under the rug – a tool that results in job discrimination, harassment, hate crime and death.

In spite of the grim pronouncements throughout Stryker’s lecture, an optimistic tone permeated her words. “Civil rights for transgender people have been expanding rapidly, with strengthened court decisions, administrative court rulings, new laws that allow for easier change of name,” said Stryker.

This optimistic view was the part of the lecture that most resonated with Jae Bates, ’18, one of the co-presidents of the University’s LGBTQ club Queer Alliance. Yet for Bates and for many members of the campus community, this lecture given by a visiting professor was a bitter reminder of the lack of transgender issues in the academia of the University.

“If we are talking ‘the institution,’ trans people are absolutely not recognized in curriculum and general rhetoric; it’s still very binary and still very cissexist (gender essentialist),” said Bates. “Most things that trans students on this campus have, have because they demanded it or created it for themselves, not because this institution did anything to preempt our pain and exclusion.”

Another University student that wished to remain anonymous concurred with Bates over the lack of transgender presence in the University’s curriculum.

“I think the University has brought a few wonderful speakers to discuss trans issues but that in the classroom it can be an afterthought,” said the student. “A majority of my classes have not asked students about their pronouns and I have not seen any classes where trans issues are central to the course material.”

Although Stryker’s lecture has already come and gone, it has undoubtedly stoked the fire of student demand for transgender representation in the University’s academia. With so many questions unanswered – including Howerton’s dilemma over his newspaper’s use of pronouns – the need for academic discussion of the subject is far from abating.