Like many other first generation students, Roger has being navigating the waters of financial aid largely on his own since the beginning of his college experience. With tuition ballooning at colleges nationwide, is there more the University can do to make college more accessible for all?

By Casey O’Brien and Allison Nasson

Editors Note: We have altered Roger Smith’s real name in order to avoid backlash targeting that individual. It is not the policy of The Trail to use pseudonyms or anonymous sources regularly, but in the course of investigating sensitive issues that may effect the personal lives of our sources, we find it necessary to do so. The full policy on anonymity can be accessed by contacting the Editor-in-Chief at trail@pugetsound.edu

Since the beginning of his college experience, Roger Smith, a current junior whose name has been changed to avoid backlash, has been navigating the waters of financial aid largely on his own.

“I’m a first generation student. My parents didn’t go to college; they know nothing about this system,” said Smith.

Smith’s first year, his aid package was $33,000 short of what he needed, so his mother took out a Parent Plus Loan to cover the difference. But that year she lost her job, became homeless and her credit rating suffered, preventing her from taking out a loan the following year.

“My EFC was zero on the FAFSA which means I have no money to give. I was homeless up here in Tacoma, my mom was homeless in LA — I had no money for education,” said Smith. Puget Sound provided a $10,000 grant, “But I still needed another $16,000.”

He went to Financial Services and was advised to take out a private loan, which often means far higher interest rates than FAFSA loans.

“I was this 18 year-old kid who had no parental support, no guidance. How am I supposed to know how to take out a loan all of a sudden?” said Smith.

Maggie Mittuch, Associate Vice President of Student Financial Services, acknowledges that there are a lot of moving pieces that have to be accounted for.

“I used to say that running a university is like running a small town. But it’s really more like running a country,” Mittuch said. “You’ve got government, you’ve got health care, compensation, student needs, desires to provide strong academic programming, desires to attract good faculty, you’ve got all of this stuff, and it has to get balanced. And then there’s the real experience of families out there, who are looking at tuition, room and board,—bill that’s pretty big—and how do they make that work?”

Smith stressed the perceived assumption within Financial Services that all students are coming to the table with a supportive family waiting in the wings.

“It feels like they expect you to have all your shit figured out — you, with your parents, or with your family — they expect you to know what you’re doing,” said Smith.

For students who come to college without parental support, or without parents who are familiar with the college financial aid system, the process of locating funding for a college education can be a difficult and even traumatic process. Smith felt that the financial aid office did not do enough to support him or others who, like him, didn’t have families able to support them fully.

“They use a lot of jargon and they confuse me, and it’s inaccessible. Half the time I don’t know what they’re talking about, and I’m sitting there, and I don’t even know how to ask them questions about their language,” said Smith. “I mean, I’m clueless about the system! Make it accessible! Make it so we understand what we’re doing, what we’re getting ourselves into.”

Mittuch wants Financial Services to be a place students feel they can, and want to, go to when they or their families are facing hardship.

“Students are always welcome to come in and talk with us when there is a change in the family’s circumstances. We have avenues that are available for them to say that ‘my dad lost his job’ or ‘my younger brother’s about to start college.’”

She recognizes, however, that there is no easy solution.

“We would all love it if our students had lower levels of unmet need. That would make our jobs so much easier. It’s just a difficult nut to crack today, especially when you think about the costs of providing education.”

The financial aid system at the University is multi-faceted and complex, and funding for students’ education comes from a variety of different sources. Puget Sound, like most residential liberal arts colleges, offers both need and non-need based aid, or merit aid. About 65 percent of students at Puget Sound receive need-based aid, but over 90 percent receive some form of aid, whether merit, financial or both.

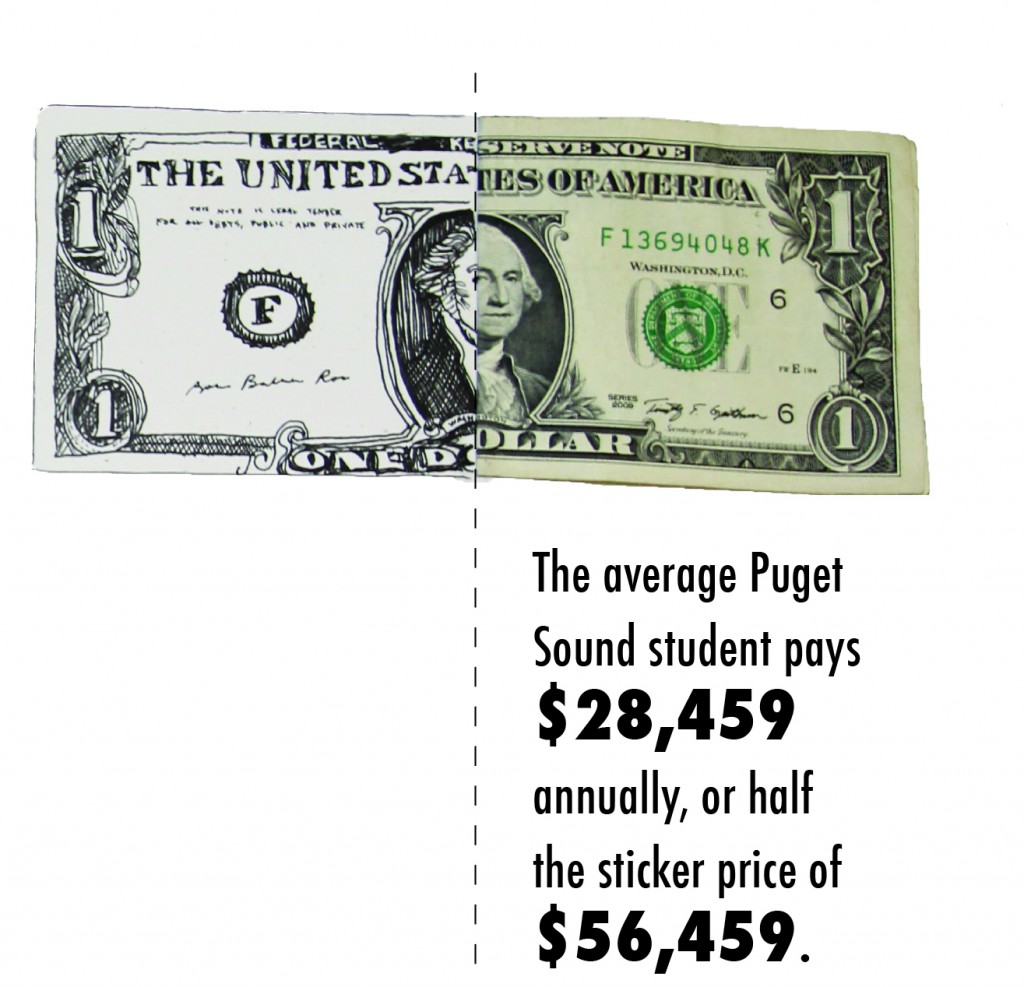

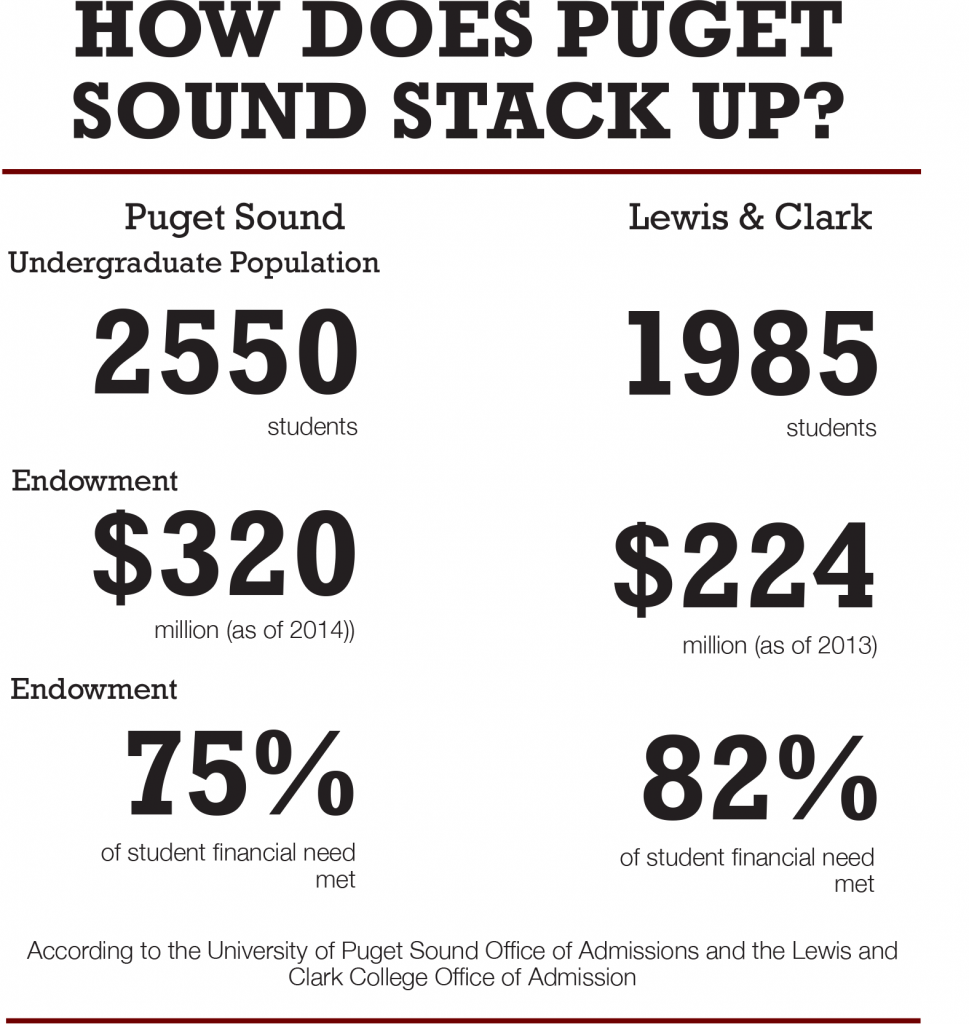

Many Puget Sound students also earn money for their education through work-study or take out private loans, as Smith did. Annual costs, including tuition, room and board, add up to $56,456, but the average amount paid by Puget sound students is much lower—only $28,459. Scholarships range from $1,500 to covering full tuition, room, board and associated fees. While Puget Sound meets the majority of students’ demonstrated need—about 75 percent—peer institutions like Lewis and Clark College meet levels of need in the range of 82–85 percent, and students at Puget Sound, like Smith, can end up with aid packages that are short of what they require to pay for college.

Dean of Students Mike Segawa feels that the disparity in met needs of Puget Sound vs. peer institutions is due to the fact that most have smaller student bodies and larger endowments, allowing for more scholarship money.

Segawa. “Before then, we didn’t have the infrastructure, or as many people dedicated to it, and frankly I just don’t think we had as much expertise as we’ve had the last ten years.”

The expansion of the endowment—which grew by over 130 million dollars through the One of a Kind Campaign —has allowed for more financial aid, and Segawa says there are plans to continue expanding the institution’s aid program. “The biggest single thing that we raised money for was student financial aid, the recognition of the gap, and the work that we have to do to make this place even more accessible and affordable than we are today,” he said, referring to the One of a Kind capital campaign.

In the last decade, merit aid has grown tremendously both at the University of Puget Sound and beyond. The growth of Puget Sound’s endowment mirrors the expansion of scholarships, particularly merit-based scholarships, at many U.S. universities. Some worry that the expansion of merit aid fails to help, or even harms, low-income students.

According to a 2013 report by the New American foundation, “Besides the very richest colleges and some exceptional schools, nearly all private nonprofit colleges provide generous amounts of merit aid, often to the detriment of the low-income students they enroll.” It argues that merit aid programs actually pull money away from financial aid programs, in an attempt to up the caliber of the student body—and tuition revenue. The foundation analyzed 479 private, nonprofit institutions, and found that at two-thirds of them, students with annual family incomes of $30,000 or less had tuition bills that averaged more than $15,000 a year even after all forms of scholarship and grant aid were factored in.

Mittuch, however, emphasizes that the line between merit and need-based aid cannot be drawn quite so clearly.

“Even though a student is going to qualify for an academic scholarship based on academic factors, it doesn’t necessarily mean that that academic scholarship isn’t helping meet need,” Mittuch said. “When you think about merit aid, it isn’t just going to people who don’t need it. It’s going to people who need it. It’s helping fill their need.”

In 2015, 41 percent of Puget Sound’s total financial aid budget went to pure need. 58 percent went to students with a combination of need and merit. Mittuch highlighted that although the University does use merit scholarships to attract students who might be able to afford more than they are required to pay, the money that they do pay is still used to enroll students with high demonstrated need.

“So they come to Puget Sound, and some of their resources help me pay the way for the kid who has both academic talent but also doesn’t have any resources,” said Mittuch, referring to students drawn by high merit scholarships. “So the reason we use academic scholarships for the kids who don’t necessarily need it is because we need them to enroll, and be here, and be a part of the community… but we then use a part of that resource that they’re bringing in to help support students that need help, for whom it wouldn’t be an option to be here without it.”

Smith feels that the allocation of merit aid to students who can afford to pay the University’s tuition is an issue.

“You’re giving people full-ride scholarships, you’re giving them full rides—I know a kid who got a full ride scholarship who can afford to pay tuition. He can afford this school! Why is he getting a full ride? Because he had that class privilege, privilege growing up to attain these different skill sets that this university admires so [explitive] much that they’re going to give you more money,” Smith said. “And the students who didn’t have that privilege growing up? They have to work… so much harder to get here.”

Some institutions have chosen to step outside of this ‘tuition arms race.’ In September of 2015, Rosemont College’s Admissions Office announced a 43 percent reduction in tuition from $32,620 to $18,500. The motivation for the change was concern over “sticker shock,” which describes a phenomenon wherein potential students with financial concerns do not apply to universities with high prices, despite the likelihood that that price would actually be steeply discounted by scholarships and aid.

Dean Segawa thinks it is unlikely for Puget Sound to consider a similar shift.

“So many of our donors want to give to financial aid… and that’s an important way of keeping them connected to this place. And so if we were to lessen the emphasis on that…it would be a very different thought process for many of our donors. We also have a good cadre of families for whom this place is affordable, and they are willing to pay the cost, given the value that they see in the education that their student will earn and receive here, and that’s another balancing point or variable here,” he said.

Mittuch also feels that the high price point of the University allows it to compete with peers to attract families that assume that an expensive college means a quality college.

“Right now, 40 cents of every tuition dollar gets turned around in financial aid. That’s a lot. So we’re discounting heavily,” Mittuch said. “If we were to drop the price and not discount as heavily… well, there’s this thing called ‘impression,’—that if your product is cheap, people don’t think you’re good. It’s ridiculous, but it’s true.”

These kind of thought processes reflect the concerns of many who feel that universities are becoming increasingly administrative, and so preoccupied with running and funding their institutions that the focus is taken off of the individual students for whom these institutions were supposedly built.

“At the end of the day, the university is a business,” said Smith. “And if the Financial Aid Office is representing the university, they’re not representing the students. And if they’re representing students, they’re representing the students that they want, that they expect, the one type of student that they think and fantasize about. And I’m not that student. And most of the students who end up in the Financial Aid Office aren’t that student.”