The rise of discourse surrounding gender and sexuality has reached unprecedented heights over the last generation. While a measure of progress is hard to determine, the strides that have been made for such marginalized individuals is still worth celebrating.

Connecting with this is the concept of “coming out,” celebrated by National Coming Out Day on Oct. 11. Individuals of non-normative sexuality and gender are commended and, to a degree, encouraged to come out of the closet and express themselves openly. As the discourse extends, so does the holiday. As the holiday extends, so does the production of cards, shirts, mugs and other merchandise.

Queerness, used here as an umbrella term encapsulating the much larger spectra of gender and sexuality, has been commodified for a public that is, for the most part, not at all queer. The national queer identity is commercialized and thereby gentrified. So what is the point of coming out, then, if the impact is no longer on the bravery and self-worth of queer individuals, but on selling rainbow t-shirts and greeting cards?

One primary point of this discussion is the relative safety of certain locations in the United States over others. Western Washington, and the Seattle/Tacoma area specifically, appears to be a place where queerness is not as openly persecuted as other parts of the nation. As such, the impact of coming out on a local level can feel safer than in the Bible Belt.

In such areas, it is not safe for queer individuals to come out, or even exist. Bigotry is vividly real in a way that we might not be able to imagine. The fact of the matter is that queerness is silenced to the ultimate degree.

At Puget Sound, a closeted queer individual might feel safer than in other parts of the world. And yet, the most fundamental part of queer identity in a world where queerness is abnormal and marginalized is community, connections and interpersonal support. On a college campus over several years, such a community is made and relationships are had, and most importantly, the identity of a queer individual evolves as that person grows in the world.

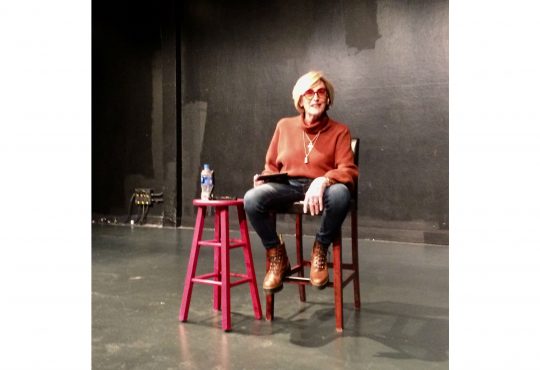

“I don’t think there’s anything inherently negative about taking a day to…look at each other and see if anybody’s got something to say. But I think it’s important to recognize that [coming out]’s not a thing that happens once,” Professor of English Laura Krughoff said.

Four years can change a person in any setting, but most of all in a place where change, learning and maturation are at the forefront of everybody’s development.

“I see young people over about four years of their life as they are moving into thinking of themselves as adults…I consistently see that evolution, and it means so many different things to so many different people. But you see the adoption of ideas, and the adoption of performances, and the adoption of aesthetics and…political movements,” Krughoff said.

“I’ve come out so many different times because my identity is so fluid… At this point it’s less about coming out as a fixed identity and rather just saying: ‘I’m queer.’ And to me, that’s not coming out – that’s me being visible, and allowing myself to be liberated in the fact that I know what my identity is,” queer artist and activist junior Adrian Kljucec said.

Visibility has been a major factor in influencing the lives of queer people as well as reaching the lives of a normative society. By being visible, individuals who choose to come out publicly give themselves as an example of their identity to a culture which might not recognize or understand what that identity means. For those still closeted, those who choose to come out engage in an act of solidarity to the silenced voices.

Despite a changing world, most of the culture in which we interact expects that people are both heterosexual and cisgender until proven otherwise through coming out. Unless those assumptions are removed entirely, the mythos of “coming out” will remain.

As long as there is a safe space with safe companions, the act of coming out carries value and can increase self-worth. “I think when one is able to come out, and wants to, I think that’s very empowering for the queer community as a whole,” Kljucec said.

When engaging in a queer space, allies are welcome, but the power should remain with those who stand without such privilege. As long as marginalized voices are silenced, the experience of our culture remains unchanged. The act of coming out is a voice that deserves to be heard, and those of the majority are obligated to hear the power of those voices.