As the Supreme Court opens its new term, it stands prepared to hear what are potentially some of the most groundbreaking cases of our generation. Think the health care ruling was big? Get ready for potential rulings on everything from the death penalty to gay marriage, and even issues over the ability of U.S. judges to hear cases on human rights abuse taking place overseas.

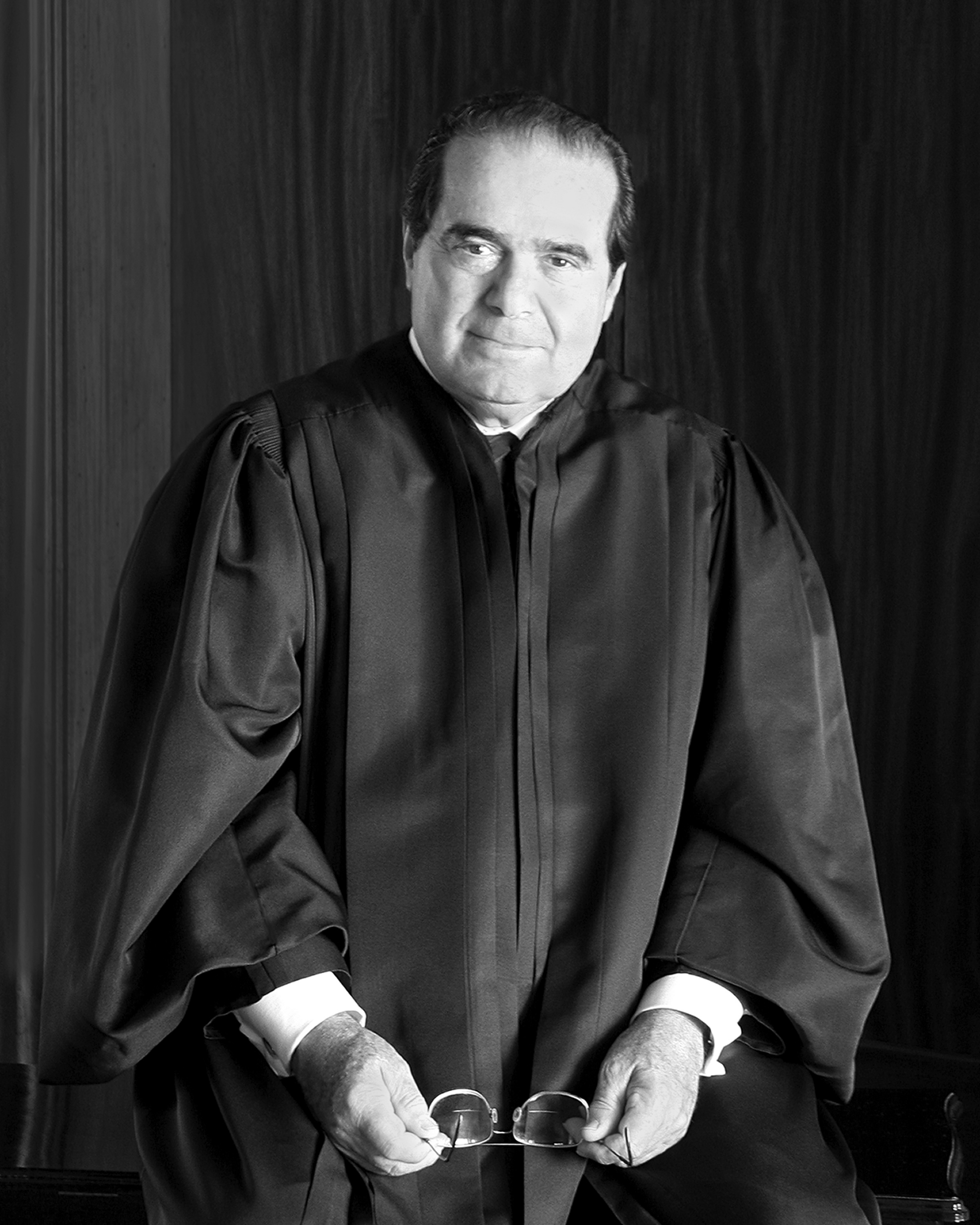

Though he probably won’t be a swing vote in any of these cases, Justice Antonin Scalia will likely be penning some of the most fiery opinions or dissents. Oyez.org the Chicago-Kent College of Law’s media site, desribes him as “arguably the court’s most colorful justice.” Appointed by Reagan in 1986, the 76 year-old jurist is famous for writing some of the most linguistically powerful rulings of the court, and when dissenting, he’s known as by far one of the sassiest judges in the country.

This summer Scalia co-authored a book with Bryan Garner entitled Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts in which he defends his theory of jurisprudence that he calls “textualist originalism.”

In this theory, the purpose of the judge is to passively interpret the text of the law as it would have been understood at the time of passage, using merely the dictionary meanings of words unless the statute in question provides an alternative definition.

While that may sound fair-handed and just, it creates some awkward and fundamentally dangerous legal black holes. In his recent article for The New Republic, circuit judge Richard Posner recounts a classic dilemma presented against Scalia’s theory: assume there was a law that said “no person shall bring a vehicle into a park.” Assume further that a child in the park is suffering a severe asthma attack and needs to be brought to the hospital. In Scalia’s theory, an ambulance would be forbidden to enter the park, because it would constitute a “vehicle” under the law, and thus be prohibited from entry.

For Scalia, “if the authors of the ordinance wanted to make an exception for ambulances,” Poser said in his article, “they should have said so.”

This theory of textual interpretation applies to civil rights as well: Scalia and his followers remain wary of ideas such as substantive due process that rely on often extra-textual protection from the law.

“The bill of rights of the former [Soviet Union] was much better than ours,” Scalia said to Congress nearly a year ago in October. “It protected free speech, street protest, and [said] that anyone caught trying to suppress criticism of the government will be held to account.”

Obviously Scalia meant that textually the Soviet constitution was superior, if only textually: there was no independent judiciary to protect it. That said, his statements offer an important insight to how Scalia thinks about civil rights. For him, it seems that they need to be protected, clearly and explicitly, in the constitution, rather than expanded gradually over time through judicial interpetation and application of the common law.

This has huge implications for cases such as the potential gay marriage suits pending before the court. While the court has not yet settled if it will hear one of the many challenges to the federal Defense of Marriage Act or if it will hear Perry v. Brown, the now-famous case challenging California’s 2008 Proposition 8, I think it’s safe to say we can’t count on Scalia’s vote for the expansion of marriage equality.

In the 2003 ruling Lawrence v. Texas (the famous case that legalized consensual sex between homosexuals), Scalia opined in his scathing dissent that “there is no right to ‘liberty’ under the Due Process Clause,” and went on to conclude that to assume a right to privacy which protected sexual acts between consensual same-sex partners “[impied] in the concept of ordered liberty is fallacious.”

All of this relies on his perverse reading of the Fourteenth and Fifth Amendments, which he reads so as to “expressly allow states to deprive their citizens of liberty, so long as ‘due process of law’ is provided.”

This reading of the Due Process clauses terrifies me: If the only protection that citizens have from the overwhelming force of majoritarian opinion is the text of the law itself, what possible recourse could they have to the judicial branch? Were all judges like Scalia, then individuals oppressed by the text of the law itself (like homosexual citizens were in the case of Lawrence), are bound to accept the decision of the majority and cannot question its constitutionality unless they can find an express sentence in the constitution that protects that right, and one which protects it textually at that.

In a speech given in Rome in the late ‘90s, reported by the Catholic News Service, Scalia showed little concern for minority rights: “You protect minorities only because the majority determines that there are minorities […] that deserve certain protection,” he said, “the majority agree to the right of the minority on [certain] subjects, but not on others.”

By this, Scalia certainly means to reference his commitment to recognizing the text of the law above all else. The law, for Scalia, seems to function as an aesthetic representation of the will of the majority, something which he sees as in itself valuable. The minority is recognized if and only if the majority wills it, and never otherwise. Rights exist if and only if the majority declares them; the ancient and unwritten common law and our common sense are not substitutes for the express and textual demands of the majority, no matter what atrocities of liberty they permit.

This is not to say that I dislike Scalia: Indeed, I would say he’s probably my favorite justice on the court right now because of his commitment to his ideas and his fiery, often sassy, dissents. He is well-known as best friends with the court’s most liberal justice, Ruth Bader Ginsberg. But that does not mean his textualism is safe. Indeed, progressives should be worried about its implications.

PHOTO COURTESY / SUPREMECOURT.GOV