Invisible Children, an American-founded NGO focused on advocacy in Uganda, has made it their goal to put an end to child armies and capture Josephy Kony, the leader of rebel group The Lords Resistance Army (LRA).

The foundation seeks to mobilize American youth to advocate for the children in Uganda by raising money and awareness to rebuild schools and provide scholarships for Ugandan youth.

Invisible Children first released a self-titled documentary in 2006 illuminating the filmmakers’ perspective on the human rights violations by the LRA. The film shows interviews and footage of child soldiers captured by Kony and child refugees fleeing the impending threat of abduction and enslavement.

This film sparked a national movement with thousands of screenings on campuses across America.

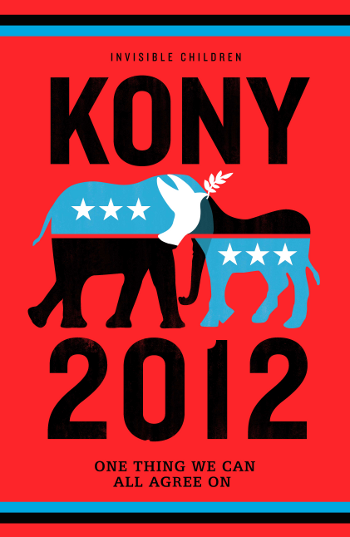

Kony 2012 is the most recent film from Invisible Children and was released on March 5. A month old and already viral, with over 86 million views on YouTube, Kony 2012 has prompted a national dialogue. The film’s goal is to promote the capture of LRA leader Joseph Kony and stop his horrendous violence. Invisible Children seeks to illuminate the atrocities of Kony’s regime and have him arrested by December 2012, when the campaign expires.

Kony 2012 reveals Invisible Children’s scheme to have Kony arrested by portraying him as the sole impediment to peace in Uganda. Director Jason Russell sensationalizes the atrocities by oversimplifying the issues. Kony 2012 is littered with momentous music, startling imagery, and the false promise that the viewer will somehow be able to stop Kony. Russell personalizes the problem, drawing empathy by paralleling the film with his son and subjective duty as a father to protect all children regardless of where they are born.

The movement gains more praise from the consumerist YouTube viewer by gaining support from 20 “celebrity culture makers,” such as George Clooney, Angelina Jolie, Oprah, Taylor Swift and Ryan Seacrest, and 12 “policy makers [with] the power to keep U.S. government officials in Africa” to assist in the capture of Kony. These influential people include George W. Bush, Condoleezza Rice and John Kerry.

While the campaign’s promotion of global awareness is certainly good, awareness alone is not going to end a violent conflict. Kony 2012 has been criticized for providing a black-and-white depiction of the violence in Uganda rather than encouraging viewers to educate themselves fully about the conflict. Individuals across America are writing letters to their representatives and signing petitions, but they are not even fully aware of the depth of the issue.

Misrepresented in the film, Northern Uganda is actually relatively peaceful for the first time in many years, which makes it peculiar that Invisible Children chose this moment to cal lfor a violent resolution. Not to mention there is minimal infrastructure in Northern Uganda to provide for the replaced child soldiers. The arrest of Joseph Kony is just one small stride in improving the situation in Uganda. Though peace talks have failed repeatedly, a non-violent resolution is strongly preferred by the populous of the region.

Conflict resolution was always going to be the responsibility of regional forces, so it is unclear to me how the awareness brought to us by Kony 2012 is the answer. The video has been interpreted as neocolonialist; it is presented as the white man’s burden to save Uganda, alluding to a sense of American paternalism.

I do see what is happening now—large regional forces from the African Unions coupled with U.S. intelligence—as a very good step, and probably the single best way to put an end the LRA, but I am still unsure how the 86 million of us who watched a 30-minute film on YouTube are doing anything to help make that happen.