By Skye Sheehy

“Horror films don’t create fear. They release it.” This quote from acclaimed filmmaker Wes Craven could not be more true. Viewers experience an adrenaline rush from the comfort of their own home or in theaters while watching horror movies. It gives people a sense of control and instills us with the confidence to handle the terrifying events depicted on screen. However, an audience’s ability to be stimulated by a horror movie is reflective of their own fears and the level at which these fears are reflected on the big screen. Horror movies have a way of taking the normalized horrors of our society and making them tangible and familiar, and give us, as viewers, the ability to come to terms with these fears. As society’s fears and tensions change with the times, so too do the trends of horror cinema.

Movies began their rise to massive popularity in the 1930s and 1940s and had become fully mainstream by World War II. Horror movies in particular solidified as a genre during this time, beginning with the 1931 release of “Dracula”. Following this solidification in World War II, the 1945 detonation of two atomic bombs on Japan shook the world. Fear of repercussions from the bomb prompted a new wave of “nuclear monster” movies in the 1950s and 1960s. These include the Japanese ”Godzilla“ (1954) and American “Them!” (1954) which both typify the genre by showcasing grotesque, futuristic monsters bent on destroying earth as a result of radiation from nuclear experiments. Science fiction horror movies like “The Fly” (1958) and “Creature from the Black Lagoon” (1954) were also concerned with the idea of dangerous scientific explorations.

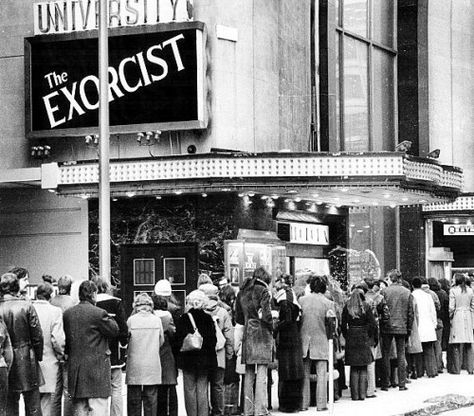

The 1950s were also characterized by widespread UFO sightings and the creation of the government study Project Blue Book, which scientifically analyzed UFO-related data and determined if they posed a threat to national security. This prompted a trend of speculative alien horror movies like ”The Thing from Another World’ (1953), “The Blob” (1958), and cultural staples like “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” (1956) and “War of the Worlds” (1953). These movies were so influential that they were later added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry. Following the Red Scare (from roughly 1947–1954), the trend shifted to psychological horror concerned with ‘the other,’ with titles like “Psycho” (1960) and “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) dominating the box office. Joseph McCarthy’s relentless hunt for the communist “other” created a deep societal fear that anyone we meet could be a “psycho,” whether it be Rosemary Woodhouse’s fellow apartment tenants, or the proprietor of a Fairvale hotel.

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the U.S.’s seemingly idyllic atmosphere was disturbed by rampant serial killer activity. Killers like Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, and the unidentified Zodiac killer garnered significant media attention. This reign of terror was reflected in the rise of slasher movies, arguably kicking off with 1974’s ”Black Christmas”.The genre includes classics such as “Halloween“ (1978) and “Friday the 13th” (1980), as well as the lengthy franchises of “A Nightmare on Elm Street” (1984–1994) and “Evil Dead” (1981–present). These genre’s villains represent the uncertainty of death that seemed to loom over the U.S., ready to strike at any moment. There was no shortage of uncertainty in the American public — events like the Watergate scandal, the Three Mile Island incident, and the Iran-Contra hearings defined the era — and audiences could find connection with the terrified characters as their supposedly perfect worlds were lacerated.

The 1990s were a decade of relative peace in the United States, as the Cold War officially ended and the rise of the internet began to usher in an era of new communication and entertainment. The boom of slashers in the previous two decades bored audiences with endless sequels, and the increase in computer-generated monsters failed to captivate moviegoers in the same way. “Child’s Play 3” (1991) and “Event Horizon” (1997) were among the most abhorred at the time, though they have since developed a cult following. To keep audiences entertained, studios initiated more cerebral, creepy horror films, with the psychologically chilling “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) and the meta parody “Scream” (1996) gaining box-office success and widespread cultural significance.

This eerie American calm was shattered by the horror the turn of the millennia brought, like the Sept 11 terrorist attacks and the start of America’s mind bendingly terrible wars in the Middle East. These events produced a pessimistic and anxious attitude among the American and global public. The trauma from these incidents, combined with the Bush administration’s support of torture to “get results” (former Vice President Dick Cheney’s referral to waterboarding as “just a dunk in the water” demonstrates this attitude well), led to the rise of the “torture porn” subgenre. Also known as splatter films, movies in this subgenre are characterized by gratuitous, often nihilistic portrayals of graphic violence. The “Saw” franchise (2004–present) and the “Hostel” series (2005–2011) both feature unwitting participants of gruesome torture who face impossible choices and harrowing obstacles that test their will to survive. The success and cultural impact of these franchises speak to the public’s struggle to comprehend the horrors that their own governments were committing at home and abroad. The rise of cell phones and social media allowed everyday people to capture atrocities easier than ever before. This phenomenon is characterized by people’s desire to document and distribute these stories to feel a sense of control in such unpredictable environments. “The Blair Witch Project” (date) and the “Paranormal Activity” (date) franchise are often credited with contributing to the popularity of the found footage horror subgenre. The 2008 film Cloverfield is another example of this subgene. It was directly inspired by the footage of 9/11, taken by shaking hands on now-ancient phones as people struggled to comprehend what they were seeing, and found there was nothing they could do but document it.

The 2010s and 2020s are difficult to define by a certain subgenre, but there is an emphasis on metaphorical and abstract concepts being explored through horror. Supernatural entities are used as an allegory for various forms of trauma, mental health struggles, and social tensions. The most popular movies of this era include “The Babadook” (2014), “Hereditary” (2018), “Midsommar” (2019), and “Get” Out (2017) , nearly all of which expose and manipulate pre-existing trauma and psychological conflict in terrifying settings. The influence of the climate crisis is also seen in this era, with movies such as “Annihilation” (2018) and “The Bay” (2012) adding to the ever-growing subgenre of eco-horror, which explores the potentially horrific consequences of ecological destruction caused by human activity. Eco-horror films have succeeded in previous decades (1963’s “The Birds” is probably the most iconic example), but as the threat of global warming grows larger every year, so does the number of films that tackle this threat.

Horror movies of all kinds have captivated audiences over the last century, and the ones we enjoy the most are those that hold a flicker of truth. A movie that completely removes itself from the climate in which it’s produced is one that leaves viewers disappointed. Movies that allow us to embrace the horror of our everyday world are the ones that endure, entertain and bring people together again and again.