By: Hannah Lee

With a total of 24,364 confirmed cases in the US and 64,290 cases worldwide, and 1 death (as of 9/21/22), Monkeypox, preferably referred to as MPV, follows COVID’s early path as the next potentially detrimental global public health threat. But what is MPV? According to the Center for Disease Control, MPV is a viral infection belonging to the same family of viruses as the Smallpox Variola virus. MPV symptoms are similar to smallpox symptoms but are milder and rarely fatal.

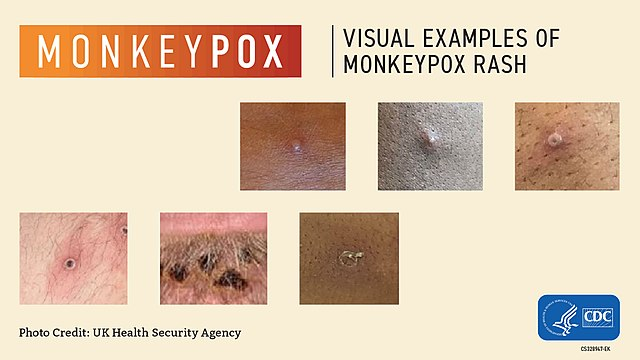

The CDC reports that when individuals are infected with MPV, they commonly develop a rash around the genital areas or anus. Other symptoms may include fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, exhaustion, muscle aches, headaches and respiratory symptoms. Symptoms usually develop within three weeks of exposure and flu-like symptoms usually indicate a rash will appear one to four days later.

As for how the virus spreads, the CDC states that MPV “can be spread from the time symptoms start until the rash has healed, all scabs have fallen off, and a fresh layer of skin has formed. The illness typically lasts 2-4 weeks.” Contracting the virus requires contact with those infected— either by direct contact with the rashes, touching objects and fabrics that the infected person has touched, or contact with respiratory secretions. The CDC website articulates that MPV can be spread during sexual intercourse of any sort as well.

The CDC currently recommends getting vaccinated against MPV if you are a confirmed close contact or if a sexual partner within the last two weeks has been diagnosed with MPV. On their website, the CDC also states, “In addition, you may want to get vaccinated if you are a man who has sex with other men or are a transgender or gender-diverse person who has sex with men and in the past 2 weeks:

- had sex with multiple partners or group sex

- had sex at a commercial sex venue (like a sex club or bathhouse)

- had sex at an event, venue, or in an area where monkeypox transmission is occurring.”

Many people have made the comparison between the handling of the MPV outbreak and that of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. According to the New York Times, when MPV was first declared a public health emergency globally, New York City Health Department officials disagreed on how to communicate the risks of the disease. Epidemiologists specifically urged officials to put out a statement advising men who have sex with other men to consider abstinence or reducing their number of partners.

Such narratives back in the 80s directly stigmatized and harmed gay men and the LGBTQ+ community. Framing MPV as an STD, even though it is not one, parallels the messages the public received during the AIDS epidemic. A striking quote from the article came from Jon Catlin, who, when speaking with the Times, said, “AIDS wasn’t treated as a crisis at first either. The quip about the ’80s is ‘the right people were dying.’” The concern now is that increased attention will breed hostility from the heterosexual community and that the queer community will be blamed for the spread of MPV.

The University’s MPV guidelines page, updated Aug. 19th, provides the same basic information as the CDC page, with the addition of how people suspected of having MPV will be isolated.