Editors note: The following article is the unabridged version of an article that ran in print on February 20, 2015 entitled “Death Grips.”

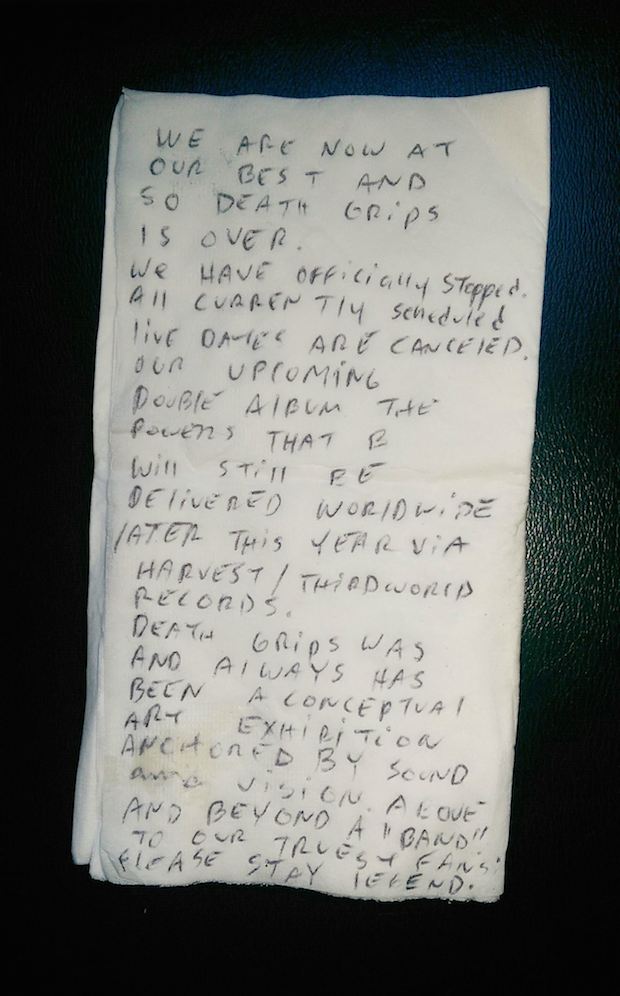

“Death Grips was and always has been a conceptual art exhibit above and beyond a band.” Thus read the soon-to-be-legendary ‘breakup napkin’ of Sacramento-based music group Death Grips last summer. The note was met with considerable backlash, but this kind of reaction was nothing new to the group, which comprised of drummer Zach Hill, vocalist Stefan Burnett as “(MC) Ride,” and producer Andy Morin, known during this time as “Flatlander.” In their short 4-year existence, Death Grips constantly attracted criticism for their actions, which at times seemed, in all fairness, designed to attract criticism.

It’s not inaccurate to say Death Grips cultivated an audience and then proceeded to alienate them deliberately. Combined with the off-putting qualities of their actual music, Death Grips was always an enigma since their inception in 2010— loved by a few, hated by many, and maybe misunderstood by all. When they broke up, all of this magnified, threatening to overshadow the actual reality of the band itself. Today, I wish to somewhat demystify this enigma, although by no means do I presume to solve it.

“Come up and get me”

Death Grips are an incredibly storied entity, and what’s more, nearly every tall tale told about the group is true. They were signed to Epic; they were dropped from Epic. They leaked their own album, then leaked angry internal emails from Epic. They rose to fame, then “deleted themselves,” as Spin’s 2014 “Artist of the Year” article (by Christopher R. Weingarten) describes it. They cancelled countless performances and timed their public actions around lunar cycles. There’s a video floating around out there of their drummer drumming in handcuffs for an entire rehearsal. And that’s not even mentioning their weird GCI-test music videos…. The myth goes on and on.

This is the band that blew their major label’s advance to live at the Chateau Marmont for two months, the Hollywood “luxury hotel” famous as a celebrity hotspot, not for the experience of its opulence but for what it represents to the rest of the world. It’s also the band that explains this move with oblique references to Magic: the Gathering (Hill, in a Pitchfork interview with Jenn Pelly about the record label debacles, cites a conversation with his brother about “control decks,” and the idea of using someone’s own power against them). Above all, Death Grips were infiltrators, breaking into spaces of power and masquerading as “one of them,” but without any of the fear of risk that is normally carried into that territory. This is why they were hardly phased or even slowed down when their actions appeared to backfire— while they had gained a lot in the preceding year, they still lived like they had nothing to lose.

All of Death Grips’ actions and music were anchored by a sense of vision and commitment to that vision that I think are rare. Despite the facade of chaos and extreme disorder, all the madness that Death Grips presents is carefully balanced behind the scenes. In an interview with musician Alec Empire at Coachella, published by ClashMusic.com, Stefan Burnett explains: “All songs are written collectively and then maximized through painstaking attention to detail. We practice the art of deconstruction with the devotion of possessed fanatics.”

“Two heavens is all I know”

Devotion is not the first word that comes to mind when you bump Death Grips— what could such a raucous and bombastic sound ever be devoted to that wouldn’t be destroyed within the first minute of its playback? Well, maybe nothing: much is destroyed to finally end up with a Death Grips track. “There’s a lot of recycling and destruction that happens in the making of our music,” Hill told The Skinny’s Briam E. Geiben, describing how they will sometimes build a track around, say, a weird YouTube sample, and then by the time the track is fleshed out remove that sample at the end, a sort of post-futurist “Erased de Kooning” moment that leaves no digital residue.

It’s all a lot to take in, but for me everything is anchored in the experience by “MC” Ride. As the vocalist, Ride is the single element of Death Grips that has at least the potential to explain everything in (very much his own) words. If Death Grips is the sound of a psychic warzone, Ride is a marathon runner from the other side of the battlefield, boldly relaying messages from our unconscious before getting swallowed up in the crossfire. Sure, he’s always yelling at us, but I think there’s more to it than that. That is, beyond all the “f*ck you’s” that he tosses out at the listener, he still throws us a bone now and then, although it might be a human one. In spite of everything, Ride is still giving us more information than the utterly inhuman bloops, blops, scrapes, and morphed samples that surround him— soundtracks that at times resemble garbage in audio form (and I say that as lovingly as possible.) If we are to imagine ourselves in the same alien computer-matrix that he lives in, we should at least appreciate Ride for showing us the ropes…just ignore the noose on the end of them. Look, what I’m saying is this: if there’s an answer the conundrum that is Death Grips, or an escape route out of the trash compactor, Ride clenches the schematics, and is reciting them from memory through barbed wire and gritted teeth.

“I’m the mask that separates them”

As the voice of the group (although unflinchingly silent in most interviews), Stefan Burnett, known by his fans as “Ride,” has always garnered a lot of attention. Ride is an intensely tumultuous character, both in his delivery and in what he is delivering. He is unstable to say the least— easily and often ‘diagnosed’ with schizophrenia by listeners. This is a claim should not be made, or taken, lightly, but there’s nothing light about Ride’s state of mind. He expresses an undeniable paranoia, experiences persistent hallucinations, and hears voices in his head. In the same interview with Alec Empire, Burnett describes his role in Death Grips with a harsh metaphor: “Lyrically, Death Grips represent the glorification of the gut…the id..summoned, tapped, and channelled [sic] before being imprisoned and raped by the laws of reason.”

Death Grips became notorious for canceling shows, or simply not showing up to them. But when they did perform, Ride was the main visual focus. Ride brought the visceral primitiveness that fans initially became familiar with in Death Grips’ records into tangible reality— on stage, he would give it a physical form. Old concert footage preserves the details: he waves his arms, shouting, howling, shuts his eyes hard, then opens them wide; they dart back and forth like those of a possessed man. Like Death Grips as a whole, Ride is both terrifying and entrancing, and the looseness of the distinction between the two is mirrored in the looseness of his body.

“NOIDED”

By modern standards, Ride’s mental balance is a bit… off, as one could maybe gather from Burnett’s own account. However, in a world where mental abnormalities are probably less understood and sympathized with than they ever have been in human history, I see an acceptance and benevolence behind the self-alienated barks and rantings of Death Grips’ iconic figurehead.

More to the point, something that always drew me to Death Grips is the way Ride portrays this experience of psychosis— it is an almost mystical kind of glorification. Against the uninviting and abrasive backdrop, Ride actually seems to play the opposite role, inviting us all into his world.

What can be made out amongst the chaos? Let’s jump to the beginning, to “Beware,” the first track off of the 2011 mixtape Exmillitary, the group’s first official release. After a brief Charles Manson sample (what else, right?), the song slowly rises, a gritty amalgamation of warbling synthesizers and stretched-out guitars, feedback, echoed chanting (“bewaaaarrrreeee”) and impatient drums. As these sounds float upwards like an ascension of out a grave, Ride narrates: “I close my eyes and seize it.” It’s a startlingly calm moment for the band, even a lucid one. Sometimes I wonder what Death Grips would have been without “Beware” serving as their introduction, a safe and rare point of orientation. In the years (and tracks, on Exmillitary) that would follow, “Beware” became the big breath you took before you went underwater; by the time the group disbanded, you could hardly remember taking it, but you must have, because you didn’t suffocate.

Ride explains his reality on this track, and also his relationship to that reality. He gives you a sense of its landscape, what’s around him, and how he himself approaches it. “I am the beast I worship,” he proclaims, assumingly in the face of all the demons that surround him. This could go a long way in deciphering the whole dynamic of Death Grips, both between Ride and the instruments as well as Death Grips’ relationship to us, the outside world.

On the surface Death Grips can sound like a very cold and mechanical band, but it’s guided almost entirely by human feelings. Ride presents those feelings in a completely unmediated form, and his extremity gives us permission to feel them too.

“My reflection, I wasn’t in it”

The truth of the matter is that Ride, and maybe also the hellish, relentless music he bellows over, is so disconnected from ‘our reality’ that listening to him gives us no choice but to go with him. As we enter his menacing network of downed power lines and pumping engines, Ride barks an alienation with which we are all deeply familiar. His transformation of all the abject loneliness and futility felt by many as a result of growing globalization, commodification, and mediation between ourselves, our world, and the people we know into a singular and enigmatic character is potentially the most authentic and honest response that has ever clawed its way into the public eye. If one just briefly considers the myriad of 21st century existential crises that humans presently face, it becomes clear that Ride’s paranoia is only half imagined; the once-irrational fear of being watched has gradually become a naked truth— the psychosis he experiences is actually a very real situation that we are all in. And we are all under these same pressures, and thus perhaps on the same trajectory that Ride himself is hurdling down. People love to think that they are somehow removed from these possibilities, to imagine that they are sovereign and immortal, that they have total control and can always keep within the boundaries they have carved out to feel safe. The creation and performance of Ride by Stefan Burnett— himself a quiet, reclusive painter— shows just how close we all are to crossing those lines, reminding us that they are drawn not even in chalk, but in the substrate of the dimmest semblance of brain activity, the quietest whisper of an already-overwritten thought.

Death Grips is over, but remember: Death Grips was and always has been a conceptual art exhibition anchored by sound and vision, above and beyond a “band.”

To the truest fans, please stay legend.