From 1946 to 1948, a physician for the National Institute of Health, Dr. John Cutler, led an experiment in Guatemala to test the effectiveness of penicillin in treating venereal disease.

In January 2010, an article written by Wellesley College research historian Susan Reverby revealed this information, which had been lost in archives at the University of Pittsburgh.

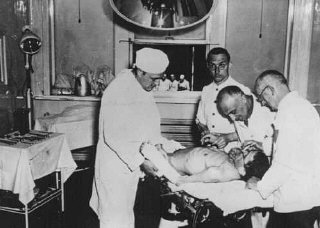

By modern standards, the methods of the experiment are abhorrent: prostitutes, soldiers and mental patients, 700 in all, were unknowingly infected with syphilis and gonorrhea by medical practitioners, then given doses of the recently discovered drug. The study quickly ended because results were not forthcoming, and rumors spread about the work.

Broken to a national audience just a few weeks ago, the story has raised issues of bioethics and political ethics. With respect to the medical concerns this news creates, the fault and responsibility of the United States are clear. Yet the political duty of the United States is far more problematic: Who owes what to whom, and why?

In the first instance, this story poses a problem of modern bioethics. Such an experiment should not have been conducted because it reduced the human patients to lab animals and subordinated their physical welfare to the scientific goals of a first-world public health system.

Moreover, in order for this to be conscionable, a xenophobic rhetoric and view of the Guatemalan citizens must have been active at the time, discounting the value of the test subjects because of their race and socio-economic class.

If one considers the issue retrospectively, this experiment is in no way morally acceptable. To do something like that as a medical practitioner and to let it happen as a politician violates the Hippocratic oath and universal human rights (a concept which was admittedly still in formation at the time).

As the news becomes clearer, the incident causes increasing shame, for it was perpetrated by a superpower in the name of liberally-defined public health interests, and against a country that has been repeatedly subordinated to the former’s political agenda — i.e. the CIA-backed coup of 1954.

The second instance of this news, in terms of political ethics, is more problematic. One might ask, “Now that this story has broken, what is the responsibility of the U.S. government to the patients in the experiment, their descendents and Guatemala as a whole?”

First, there is rhetorical courtesy: President Obama called Guatemala’s president Álvaro Colom to apologize — although there will probably not be a Cerveza Summit — and both Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sibelius issued a joint condemnation of the experiment.

“Although these events occurred more than 64 years ago, we are outraged that such reprehensible research could have occurred under the guise of public health,” they stated.

Second, there is an optional penance. One might argue that the United States ought to do something to make up for what now is considered a grave moral transgression committed by a government embodied by the mengelian Dr. Cutler, who infamously led the Tuskegee experiment of 1932 to 1972.

Therein, African American sharecroppers with syphilis were deceived into thinking that they received treatment, while researchers withheld antibiotics to observe the natural development of the disease and the patients’ immuno-responses.

If any patients from the Guatemala experiment are living today, the full details of the study ought to be disclosed to them and they should be given a personal apology. A monetary compensation might be appropriate as well, gauged in terms of the negative health effects that the patient could have suffered, even if they did not.

But what is required of the U.S. on a larger scale, by way of reparations?

Some have called for a payment to the entire Guatemalan citizenry as a way of establishing positive and ethical health programs in Guatemala. (Note: Guatemalan authorities did allow the American researchers to undertake the experiment.)

That decision will be left for the righteous, resentful and attentive on either side of the border to figure out. With the election concerns that now plague the Obama administration this matter will likely be overlooked.

Time and distance from the racism of such medical experimentation and the interventionist Monroe Doctrine have made this story a ghost ready to haunt, but likely to be shoved back into the closet of the American social conscience, where the descendants of African slaves and First Peoples wait to this day.