No, this isn’t a story pulled from The Onion: Birmingham, Ala. is raising a challenge to the Voting Rights Act in federal court. On Friday, Nov. 9, the Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal in Shelby County v. Holder, challenging the constitutionality of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

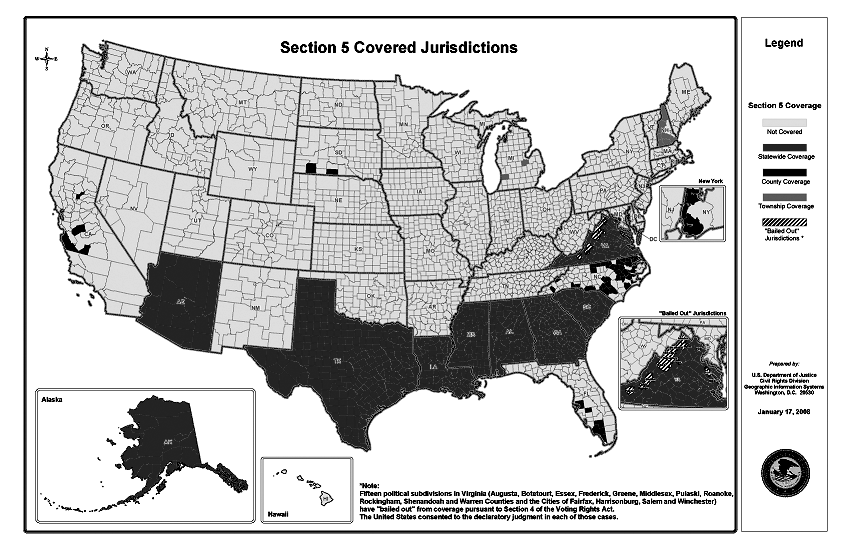

The controversy is over the “preclearance” requirements of Section 5: The 1965 law requires certain “covered jurisdictions” to request permission from the federal government before making changes to their local voting laws because of a history of racial discrimination in voting. Shelby County claims that conditions in 2012 do not mirror those of 1965, and that therefore Congress does not have authority to continue enforcement of the law against certain jurisdictions.

The appeal comes from Shelby County, Ala., a largely white suburb of Birmingham. The County claims that Congress exceeded its constitutional authority when it voted to extend the Voting Rights Act in 2006, while the government maintains (and all lower courts in this case agree) that it is a “congruent and proportional remedy” and necessary to enforce “the commands of the Fifteenth Amendment.”

The fact that this case is even up for appeal is ridiculous: The Voting Rights Act has been one of the most successful pieces of civil rights legislation of all time and has greatly increased minority racial turnout in elections.

What’s potentially more offensive, however, is that Shelby County’s argument boils down, no matter how you read it, to a variant of “Let us be racist, please.”

The standard that they ask the Supreme Court to adopt in this case is equally ridiculous; in covered jurisdictions, appelants contend that the government should have to prove that the “unremitting and ingenious defiance” of Alabama’s 1965 politicians still persisted. In effect, to enforce voting equality, the county maintains, the government has to prove that politicians are still trying to block school integration. Not only is this contrary to the entire history of federal jurisprudence establishing supremacy over state law, but it ignores that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments vested in Congress “power to enforce” the protection of civil rights. That means that if Congress determines there is still discrimination in voting practices in 2012 that Shelby County has to deal with it.

And what are they afraid of? Currently, all they have to prove when making voting changes is that the change will not negatively impact racial minorities. That doesn’t seem too unreasonable to me. In fact, I wouldn’t mind if the Voting Rights Act was extended to cover all counties in the United States: We should not be afraid to prove that whatever changes we want are not racist. And if, after review by the federal government, it is found that changes would be in either intention or implementation racist, then we should be happy to go back to the drawing board.

I’m worried, however, that the Roberts Court will not agree with my analysis.

In an earlier case, the Court signalled that significant portions of the Voting Rights Act may be outdated or in need of judicial review. Though the court has previously held that allegations of racial discrimination justify the use of “strict scrutiny,” the harshest and most intense standard the court can apply against a law when judging its constitutionality, it may default to a lesser standard in this case because of this history of signals the court has sent Congress.

If the court adopts the idea that the government must prove that current conditions are identitcal to those of 1965, then I fear that the elegance of a “strict scrutiny” may be washed away by skepticism of Congressional authority in this case.

Were that to be the case, the important duty of protecting minority rights would be subsumed into an obscure and arcane question of textual delegation of power to Congress. In short, the real, material harm of allowing racial discrimination in voting may continue because a few old, rich men may rule that Birmingham, Ala. (of all places!) has “had a hard time.” Oh, I’m sorry Birmingham, you had a hard time trying to implement voter equality? I’m so sympathetic.

When the Supreme Court entertains petitions like this one, I really fear for how our Constitution gets interpreted. The retreat into the ivory tower of the courthouse often means that material oppression can be justified through ancient legal procedures, something I think is unacceptable.

Of course, the court can be a shield protecting minorities against a tide of oppression (just look to the recent gay marriage cases, free speech cases and, of course, the original cases when the courts asserted the force of the Constitution against the South to win school integration), but the Roberts Court does not often jump up for the defense of racial, gender or sexual minorities.

Indeed, the Roberts Court often lets arcane matters of administrative law come to impede civil rights and progressive causes such as fair pay and protection from torture commited by corporations. The conservative bloc (Justices Roberts, Alito, Thomas and Scalia) and the moderate Kennedy often unite to place administrative matters on a pedestal while casting civil rights as old jurisprudence, as something of the past, all settled and ready to be tucked into bed forever.

(Justices Roberts, Alito, Thomas and Scalia) and the moderate Kennedy often unite to place administrative matters on a pedestal while casting civil rights as old jurisprudence, as something of the past, all settled and ready to be tucked into bed forever.

What they and Birmingham ignore, however, is that these acts were passed for a reason, and that these are rights expressly protected by the Constitution. Of course, all nine justices know that the Constitution protects citizens from discrimination based on their race in voting, but often the “prior” questions of standing and appelate procedure come to dominate court opinions and, in effect, that matters of obscure legalese doctrine take precedence over matters of material oppression.

That’s an approach to legal interpretation I can’t get behind: That formalist matters of procedure and standing can be used to justify oppression merely means that those standards are part of the apparatus of domination that gave rise to slavery and racism in the first place. They are a way to mask racism behind a veneer of legal intepretation.

A ruling on the case is expected by June, and everybody should keep their eyes on this case. Justices do listen to public opinion, whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, and continuing to put pressure on them to uphold the Constitution’s guarantee of equality for all is one of the best ways that we non-lawyers can contribute to the legal process. While we’re not able to join the actual court proceedings in D.C., we can write letters and petitions, and make sure that we’re at least being heard.

If the court rolls back an act that’s been in place for 47 years because Birmingham has had a hard time, that would be a greatest travesty of justice the Roberts Court could possibly enact.