Two local artists reconcile memory and aging in ‘Memory Lame: An Unforgettable Installation’

Jessica Spring and Scott Gruber’s “Memory Lame: An Unforgettable Installation” is an equally reverent and playful exhibition. The artists capture the frustration and wistfulness of aging, memory loss and the acceptance of change.

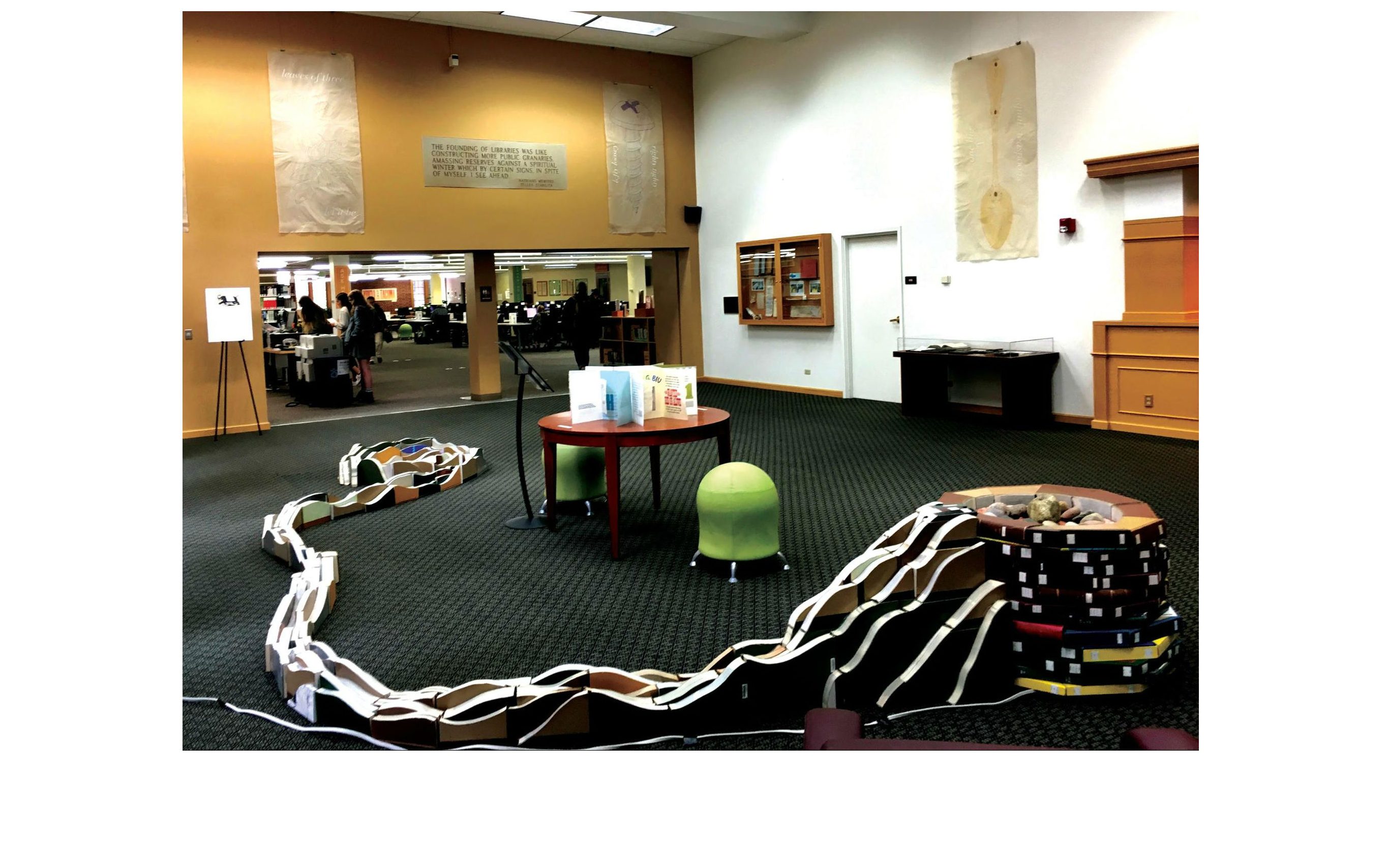

“Memory Lame: An Unforgettable Installation” sits in the center of a busy university library, but its intimate material and energetic use of space demand attention. The exhibition explores memory loss, memory retention and the replacement of old tools with digital technology. The exhibit has been on display in the Collins Memorial Library since Oct. 22 and will remain until Jan. 25, with an opening reception on Dec. 5 at 6 p.m.

Jessica Spring’s letterpress prints have been featured in collections nationally and internationally. She is an instructor of book arts at Pacific Lutheran University and owns a small business in Tacoma called Springtide Press.

Spring’s pieces are not only thoughtful and well-crafted, but they are also deeply personal. The pain of watching her father’s memory and livelihood decline from Alzheimer’s disease led her to explore memory and cognition in her work. Before he passed away, Spring and her father created an installation inspired by memories from his childhood.

“He was so engaged with the project, helping me sort everything from shoeboxes to final installation, and this inspired him to recall childhood stories,” Spring said in an email interview with The Trail. “The work both gave us a way to engage and provided some solace.”

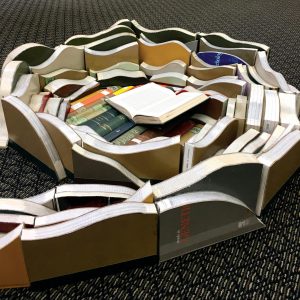

Engagement is important to Spring; the “artists book,” in the center of the exhibit is designed to engage with its reader. The book works like a puzzle: it flattens and then must be put back together through clues and corresponding shapes.

“In the same way I like to challenge readers’ senses, I hope to provide layers of engagement. A reader can spend some serious time with the artist’s book or just cruise by to ponder the fountain or read a banner,” Spring said.

“Artists book” is meant to be a physical manifestation of a “Memory Palace,” a technique that uses an imaginary place and mnemonic clues to recall information. Different sections of the piece include various memory methods like mnemonics, prints of herbs thought to aid memory and a poem meaningful to her father, “Forgetfulness” by Billy Collins, repeated in each section.

Spring’s “mnemonic banners” display drawings of plants and mnemonics in large text. The giant hanging banners are made from handmade abaca paper. Abaca, a plant from the banana family’s strong fiber, can be beaten and made into translucent sheets of paper. The process is laborious but as Spring explains, encapsulates memory in itself.

“It was an eerie color and texture too, almost like skin, and the papermaking and drying process is literally recorded in each sheet, a memory,” Spring said.

The largest piece in the exhibit, “Fountain of Knowledge and River of Forgetfulness,” was created by Scott Gruber. Scott Gruber earned his BFA in sculpture from St. Cloud University. He creates functional and non-functional sculptures and owns Calendula Farm & Earthworks in Tacoma.

“Fountain of Knowledge and River of Forgetfulness” is a real running fountain. Its cascading body is made from bound periodicals and journals that the Collins Memorial Library replaced with digital copies. The books used were all chosen to reference memory, ideas and cognition. The piece seems to reconsider what is lost with digital technology: solid intimate sources of knowledge that can be held in one’s hands.

Gruber’s “Fountain of Knowledge and River of Forgetfulness” and Spring’s mnemonic banners converge and continue outside. The work is left exposed, and the viewer can look out the window and watch it succumb to nature and eventually disintegrate. This sentiment parallels the breakdown of memory with Alzheimer’s and old age and reminds us that everything will eventually disappear.

Whether a casual viewer just passing by the installation or a serious observer sitting and engaging with “artists book,” anyone can engage with the exhibit. Its serious subject matter reminds us of the impermanence of life, while its clever and sometimes comical mnemonics provide much-needed relief.