By Karlee Robinson

CW: Discussion of terrorism, racial prejudice

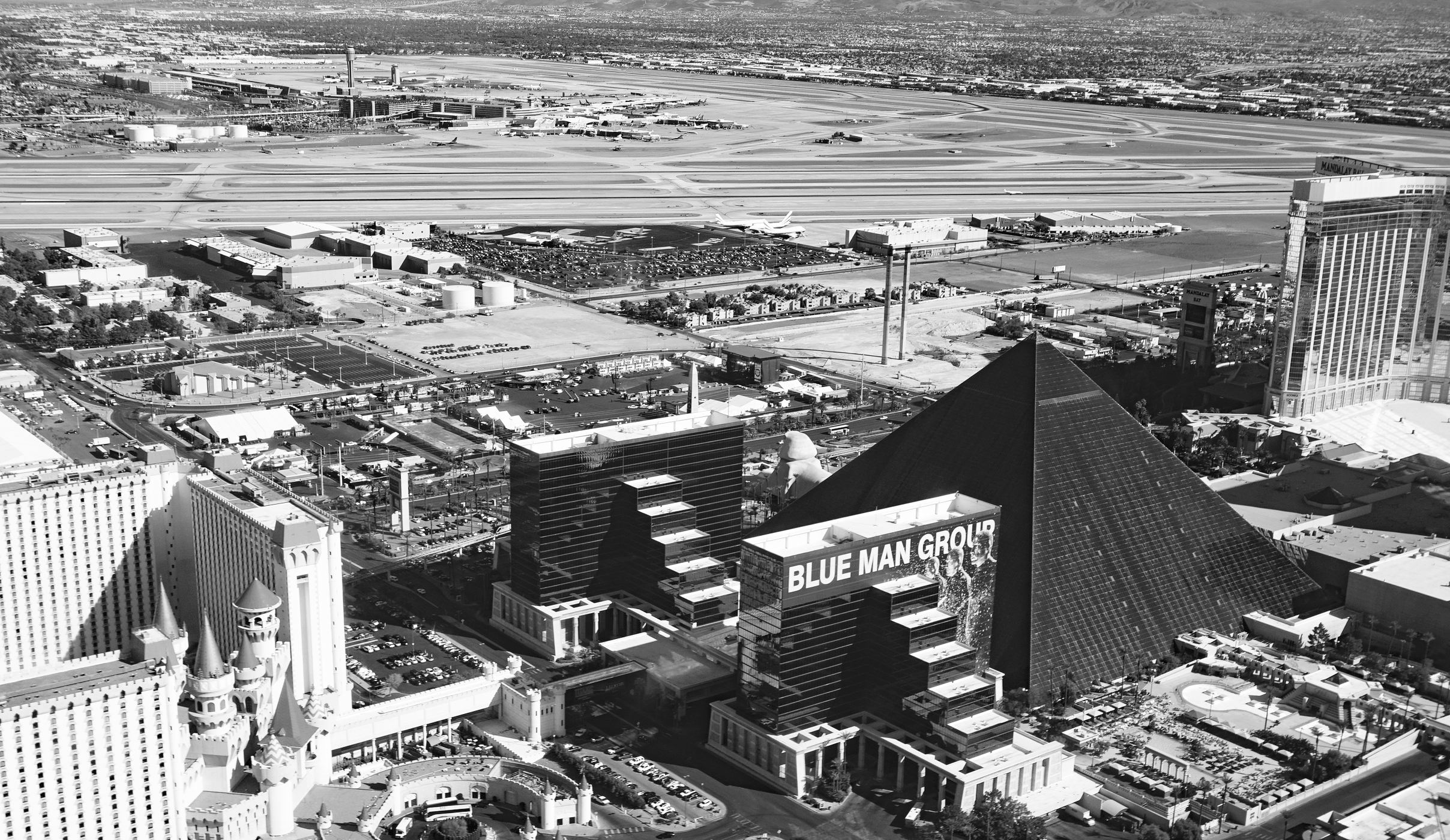

A gunman, Stephen Paddock, stationed on the 32nd floor of Mandalay Bay hotel opened fire on a large crowd of concertgoers at the Route 91 Harvest music festival on the Las Vegas Strip on Oct. 1. Victims are in search of answers, while explanations pose discussion on prejudice and reclaiming the power of music.

Leaving 58 people dead and 515 injured (updated Monday, Oct. 2 by Clark County Sheriff Joseph Lombardo), it’s fair to assume Paddock had an identity of extreme and irrational behavior, but there is little that we know about him to suggest this reality.

Paddock had no criminal record or military experience. On a 2014 real estate application, Paddock said his income came from “gambling,” and later is said to have told a real estate agent he gambled $1 million per year. Paddock was significantly wealthier than the average mass shooter (according to reports compiled by Mother Jones and a 2014 study of American mass murderers by Eric Madfis, a University of Washington-Tacoma sociology professor) and owned two planes and multiple homes. Other than his white male identity, Paddock defies the stereotypical character and lifestyle trends of past mass shooters.

In an interview with CBS News, Paddock’s brother Bruce stated, “We have nothing to say, there’s just nothing we could say. He was my brother … He gambled, he was nice to my kids when they went out to Vegas, my kids didn’t know him that well. He sends his mom cookies — there’s nothing else to say. … [He had] no religious affiliation, no political affiliation, he just hung out.”

Reasoning towards a motive, could this all be explained by a simple adrenaline high? Routine autopsy reports conducted last week by Vegas coroners conclude no obvious sign of tumor, injury or abnormality. Paddock’s body has been transported to Stanford University, where they will continue more studies. It’s important to be considerate of sensitivities surrounding these events. Is motive really significant when the loss is of such a great scale?

Recounting the earlier Manchester Arena suicide bombing on May 22, 2017, in which a shrapnel-laden homemade bomb was detonated by Salman Ramadan Abedi following a concert by American singer Ariana Grande, an act which killed 22 people including the attacker, it’s unsettling to write off the similarities between this act and the Vegas shooting as mere coincidence. Where their means of violence differ, their settings are essentially identical, illustrating discontent’s invasion of sacred expression.

Music’s expression is intended to productively communicate a need for change, not abhorrent acts of baseless frustrations. Perpetrators are abusing music to project personal distraught on undeserving bystanders. They’re abusing its power even when their intentions are completely separate from the realm of music. While Paddock’s actions remain absent of an explanation, perhaps his violent expression found a haven on music’s stage because he knew it’s realm is untouched by normal government and social restrictions.

Music effectively speaks to the public in ways uninhibited by normal government and social restrictions and with this, has a strong history of voicing counterculture.

Its dialogue is direct and it isn’t censored by the government or oriented around media. Music manages the capacity of personal experience, while maintaining intentional clarity. If nothing else, music is authentic. Music illustrates that which goes against the social expectations of the time, so what are the implications of terrorizing attacks in the center of musicians’ stage?

It’s important to also acknowledge how ethnicity plays a role in seeking explanation.

If Paddock wasn’t a white male, it’s certain the public wouldn’t be seeking explanation as desperately as they are now.

Looking back to the Manchester Arena bombing, while ISIS claimed responsibility, it’s important to realize how the similarities between the Vegas shooting and Manchester Arena bombing support awareness of human capacity; specifically, human capacity for violence and how it isn’t defined by race. It’s clear both tragedies held different intentions, but the results are enough to encourage broader caution, not caution according to race.

The behavior Paddock performed contradicts those we’ve been socially conditioned to assume, but behavior is not exclusive to specific races, and where the proof Vegas provided is not evidence anyone would beg offer, it stresses the importance of viewing conflict through an objective lens. If doing so, we can work towards avoiding tragedy at the fault of overlooking prejudices. That doesn’t go to say these events are an explicit example, but serves well to bring these thoughts to the forefront.

Music was once an outlet for the unfamiliar, encouraging progress down new avenues. When this progress manifests in the form of violence, all is lost. The horrific Vegas shooting — while emphasizing security dilemmas and existing racism — illustrates a broader picture that reflects chaos in both social and political climate. The Manchester Arena suicide bombing serves as another example.

Paddock took the power of music by abusing its stage. Paddock took the grounds on which counterculture’s dialogue evolves. Most painfully of all, Paddock took lives. The strength victims showcased on the night of events — concertgoers combing the grounds for survivors and carrying out injured — proves we can reclaim the sanctity of music to honor those lost.