What does it mean to speak well? In my opinion, one must above all else speak with clarity. One must avoid words and grammatical constructions that hinder one’s message. “Like” is such a word. Far too many students, even at this fine University of Puget Sound, are guilty of using “like” in an improper way.

“Like” is a powerful word. It is short, loud and somewhat abrasive. Between the “l” (what linguists call an alveolar lateral approximant) and the “k” (a voiceless velar plosive or stop), is an “i,” which because of its pairing with the silent “e,” becomes long. This is equivalent to the diphthong /ai/.

Because of its soft beginning, “like” comes to the tongue easily. But because of its strong ending, it leaves an impression on the ear. It was precisely on this impression that Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1952 presidential campaign capitalized with its “I like Ike” slogan.

When used improperly, “like” most commonly acts as a filler or place-holder. One needs hardly to recall Franka Zappa’s Valley Girl for examples of this use. Here more than elsewhere the loudness of “like” is intolerable.

“Like” is too abrasive to be used instead of “um.” “Um” has a soft, soothing quality. Its sound is similar to the onomatopoeic word “hum,” or even to the sacred syllable “Om” of the Indian religions. While “um” has its own grammatical problems, it is a far smoother filler than “like.” When students pepper their phrases with “like,” they sound staccato, jarring and unpleasant.

In its other improper uses (or colloquial uses, as less scrupulous observers say), “like” becomes as an adverb, or a quotative. As an adverb, “like” means something in the way of “nearly,” such as in the sentence “Amanda laughed so hard she like peed her pants.” As a quotative, “like” introduces a quotation or impersonation: “Dale was like, ‘You guys are so drunk’.”

[Photo Courtesy / Jesse Baldridge]

In both sentences, “like” introduces ambiguity. How close to peeing her pants was Amanda? Did Dale actually accuse someone of being drunk?

When it is used correctly, however, “like” is fairly meaningful. In good grammatical health it functions as a noun, verb, adjective, conjunction or preposition. One can speak of “likes and dislikes” (nouns), or one can ask “but do you really like him?” (verb). Consider the prepositional use in Madonna’s famous line “like a virgin, touched for the very first time.” Consider also Shakespeare’s couplet “Like as waves make towards the pebbled shore/so do our minutes hasten to their end.”

In these last two examples the most important proper syntactical use of “like” is revealed. “Like” as a preposition sets up a comparison or simile. The logic of the simile is that one thing acts merely in a similar manner to another, not as the other thing itself.

So, the paradoxical theme of Madonna’s 1984 hit (which was actually written by Billy Steinberg and Tom Kelly) is not a virginal experience itself, but something similar to but ultimately different from it. Nor, in Shakespeare’s line, do minutes actually hasten to a shore, for that would be absurd.

The abrasiveness of “like” can be harnessed for good in this proper prepositional use. An eloquent speaker can use the somewhat jarring word to signal to his audience that he or she is diverging into simile and that the phrases following “like” should be weighed differently from those that came before. An eloquent speaker in this way demonstrates his or her mastery over an important feature of our English language.

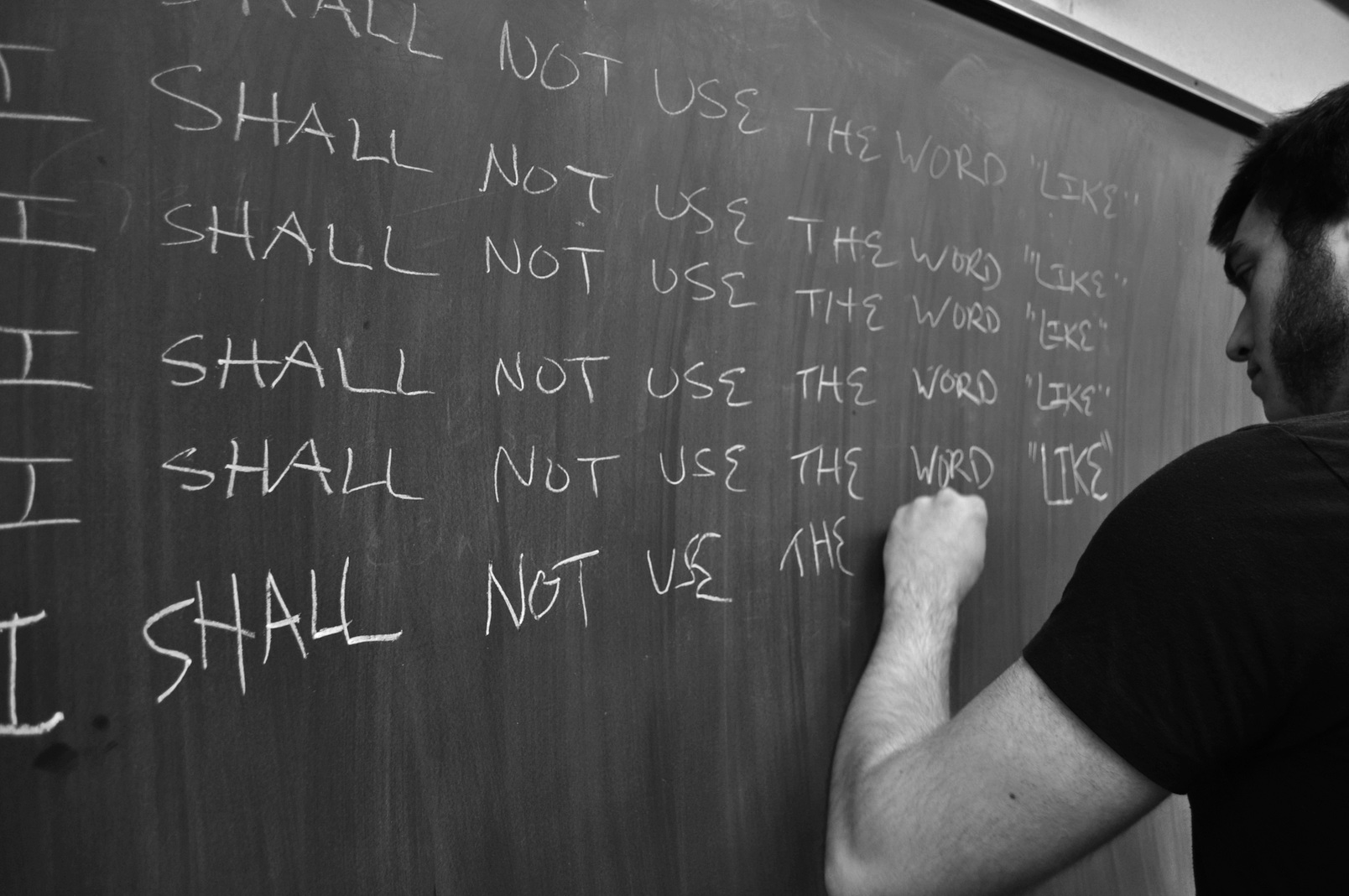

Students of the University of Puget Sound should be eloquent speakers. They should not burden their phrases and banter with improper uses of “like.” When a student bombards a classroom discussion with “like” in an incorrect way, he or she distracts from the essence and purpose of what he or she is saying. He or she who uses “like” incorrectly acts against his or her purposes. On the one hand, speaking expresses a desire to be heard and understood. On the other hand, garbling one’s speech with “like” diminishes how much of what one says is understood.

Whether one majors in Mathematics, Classics, Chinese or Biology, one needs to speak well to be understood. To burden one’s utterances with abrasive place-holders or to introduce ambiguity into one’s descriptions is to diminish clarity.

[Photo Courtesy / Jesse Baldridge]